Modern Skepticism’s Unique Mandate

Today I thought I might share another excerpt from my two-chapter “Why Is There a Skeptical Movement?”(PDF)—the section that comes immediately before the “‘Testable Claims’ is Not a ‘Religious Exemption’” excerpt I posted last week. (My apologies for any confusion in presenting these out of their original order.) Both excerpts are taken from the second chapter of “Why Is There a Skeptical Movement?” I encourage anyone interested in the topic of scientific skepticism—enthusiasts and critics alike—to consider the larger piece in its entirety if at all possible. (It’s free.) Part One delves into the long, useful, and (I think) noble tradition of scientific skepticism, tracing its development alongside the scientific mainstream in the twentieth and nineteenth centuries and beyond—all the way back to classical antiquity. This excerpt today assumes you’re familiar with the fact that serious attempts to study, investigate, and understand paranormal claims (and to rein in or expose paranormal fraud) go back a very, very long way. Today we’ll consider the context of the most important “recent” milestone on that long road: the founding in the 1970s of formal groups dedicated specifically to the pursuit of scientific skepticism as an organized public service project. (See Part One of “Why Is There a Skeptical Movement?” for further details regarding this and earlier examples of skeptical organizing.)

Modern Skepticism’s Unique Mandate

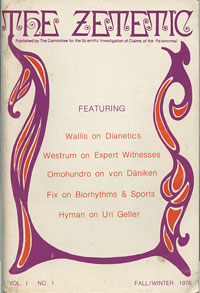

The 1976 founding issue of North America’s first periodical dedicated to scientific skepticism—now known as the Skeptical Inquirer.

If the critical study of paranormal claims extends back to antiquity, why do most skeptics consider the 1976 formation of the first successful North American skeptical organization, CSICOP [the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, since renamed CSI, or the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry] to be the “birth of modern skepticism” (at least for the English-speaking world)?

The difference is between the long-standing genre of individual skeptical writing, and the recognition that this scholarship collectively comprised a distinct field of study. With the creation of an organization to pursue that work (and soon the emergence of a global network of many such groups) came the accoutrements of any serious field: discussion of best practices; recognition of specialist expertise; periodicals for the publication of new research; infrastructure such as legal entities and buildings; and, eventually, even professional positions for full-time writers and researchers. Together—falteringly, at first, but together—these newly organized skeptics got to work on their unique mandate.

To better appreciate the dimensions of that distinct mission—the much-discussed “scope” of scientific skepticism—it’s necessary to consider the other movements, organizations, and scholarly fields that already existed in North America before CSICOP was formed:

There was already an atheist movement. Although the term “New Atheism” dates back only to 2005, American Atheists was formed in 1963.1 Thirteen years before the formation of CSICOP, atheist activists had already overturned school prayer in the United States Supreme Court—and of course the “Freethought” movement goes back much further. German Freethinkers who flowed into the United States in the mid-1800s established groups that still exist today. (The oldest I’m aware of is the Sauk County Freethinkers, established in 1852, whose first Speaker wrote that the means to “mental and moral freedom…are not ‘supernatural and incomprehensible means of grace,’ but the natural and comprehensible means by which a human being influences and inspires the mind and heart of his fellows—through speech, song, and the mutual exchange of opinions.”2)

Being a part of that Freethought tradition, there were of course already humanist organizations and humanist media many decades before CSICOP was formed. In fact, CSICOP was a spin-off from the venerable American Humanist Association. It was conceived at an AHA conference3 as a distinct group with a distinct mandate. Founder Paul Kurtz recalled, “CSICOP was originally founded under the auspices of the Humanist magazine, sponsored by the American Humanist Association. But the Executive Council decided immediately that it would separately incorporate and that it would pursue its own agenda.”4

Similarly, before CSICOP there were already groups and movements working to advance democratic ideals, civil rights, and feminism. There were already groups fighting for gay rights, for church-state separation, and against racial discrimination. There were already environmental groups.

Likewise, science advocates already existed. There were already science popularizers. Science education and science journalism were established professional fields before CSICOP came along.

CSICOP was even predated by an existing movement to promote critical thinking (a movement that still exists) known not-too-creatively as “the critical thinking movement.”5 Since the 1970s, this educator-driven pedagogical movement has been hard at work on a project that skeptics sometimes imagine we should invent: reforming education across all grade levels to teach critical thinking skills, in order to foster a more rational society. Without any particular contact with (or need for) the skeptical movement, the critical thinking community boasts its own non-profit organizations, technical literature, and decades of annual conferences.

With all those movements doing all that work, why bother forming CSICOP? If other movements already promoted humanism, atheism, rationalism, science education and even critical thinking, what possible need could there be for organizing an additional, new movement—a movement of people called “skeptics”?

Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal

The skeptical literature is the work of many decades. Here, for example, is the cover of Skeptic magazine’s premiere issue, published 21 years ago. (Asimov portrait by Pat Linse.) Subscribe today to support our ongoing work.

CSICOP—and with it the global network of likeminded organizations that CSICOP inspired, such as the JREF and the Skeptics Society—was created with the specific yet ambitious goal of filling a very large gap in scholarship. The skeptical movement sought to bring organized critical focus to the same ancient problem that isolated, outnumbered, independent voices had been struggling to address for centuries: a virtually endless number of unexamined, potentially harmful paranormal or pseudoscientific claims ignored or neglected by mainstream scientists and scholars. “The gap means there is a danger that high-level scientific competence may not be applied in examining paranormal and fringe science claims,” explained Skeptical Inquirer Editor Kendrick Frazier in 2001. “This is where I think CSICOP, the Skeptical Inquirer, and the skeptical movement in general come in. We help fill that gap. We are in effect a surrogate in that area for institutional science.”6 Many of the people who undertook the work of this newly organized skepticism were personally motivated by the social justice implications of this neglected gap in scholarship (shouldn’t someone protect the sick from con artists?) but it was the gap itself that they organized to fix.

In 2001 Paul Kurtz recalled, “I am the culprit responsible for the founding of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Why did I do so? Because I was dismayed in 1976 by the rising tide of belief in the paranormal and the lack of adequate scientific examinations of these claims.”7 Setting the “rising tide” rhetoric aside (every generation of skeptic has interpreted the paranormal as posing a uniquely urgent problem in their time) the mandate at CSICOP’s inception was very clear. Organized skeptics would set aside a priori scoffing and strive to become honest brokers, actively working to learn what light the methods of science and scholarship could shine on the vast and long-established portfolio of skeptical topics.

To that end, the scope of the skeptical project was explicitly defined as the investigation of exclusively empirical claims—not just additional opinion, not merely an attitude of doubt, and not simple sniping from the other side of the burden of proof. The first issue of North America’s founding skeptical periodical was unapologetic about this just-the-facts mandate.

This journal, the official organ of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, is intended to communicate scientific information about the many esoteric claims that have shown a growing influence upon the general public, educational curricula, and scientific institutions themselves. … Finally, a word might be said about our exclusive concern with scientific investigation and empirical claims. The Committee takes no position regarding nonempirical or mystical claims. We accept a scientific viewpoint and will not argue for it in these pages. Those concerned with metaphysics and supernatural claims are directed to those journals of philosophy and religion dedicated to such matters.8

That same inaugural issue of the magazine that would soon be renamed the Skeptical Inquirer amplified that “the purpose of the Committee is not to reject on a priori grounds, antecedent to inquiry, any or all claims, but rather to examine them openly, completely, objectively, and carefully.”9

Think about the sheer, sustained toil this aspiration called for. After all, it’s not easy to be open-minded about every bizarre question to come down the pike, let alone to try to solve them all—and it doesn’t get easier after you’ve seen a thousand similar claims come to nothing. Nonetheless, although skepticism is often denigrated as a club for scoffers (even, if you will, “scoftics”10), the goal for CSICOP was the opposite of armchair debunking. Kurtz explained in 1985:

How shall people in the scientific and academic community respond to the challenge of paranormal claims? The response should be, first and foremost, ‘By scientific research.’ In other words, what we need is open-minded, dispassionate, and continuing investigation of claims and hypotheses in the paranormal realm. … The dogmatic refusal to entertain the possibility of the reality of anomalous phenomena has no place in the serious scientific context. The hypotheses and data must be dealt with as objectively as possible, without preconceived ideas or prejudices that would mean the death of the scientific spirit.11

Organized skepticism was thus not the place for people to talk big about their beliefs or their disbeliefs, but instead to ante up concrete evidence one way or the other. As Kurtz bluntly concluded, “proof or disproof is found by doing the hard work of scientific investigation.” After all, opinions are like noses12—everyone’s got one, and everyone already had one without organized skepticism. Scientific skeptics set out to discover and provide something more useful: demonstrable, verifiable facts on which the public could rely.

CSI’s “follow the evidence” approach (I hope I may be forgiven for hearing hits by The Who in my head when attaching the word “evidence” to CSICOP’s new name) became the enduring engine for an organization, which grew into a network of organizations, which grew into a movement. When I discovered skepticism (over 20 years ago) the empirical “testable claims” approach had been long established as the skeptical movement’s central unifying principle—as central to skepticism as evolution is to biology.13 The Skeptics Society, for example, was from the outset committed to this scientific framework. “With regard to its procedure of examination of all claims, the Skeptics Society adapts the scientific method,”14 affirmed the first issue of Skeptic magazine in 1992. “The primary mission of the Skeptics Society and Skeptic magazine,” Michael Shermer emphasized elsewhere, “is the investigation of science and pseudoscience controversies, and the promotion of critical thinking. We investigate claims that are testable or examinable.”15

The sheer overwhelming practicality of concentrating on the investigable16 aspects of paranormal claims—of investigating those things which can be investigated—inspired a generation of skeptics like me. As Steven Novella and David Bloomberg explained in 1999, “The position of scientific skepticism is consistent, pragmatic, and allows the skeptical movement to precisely and confidently define the focus of its mission.”17

It was also the best guarantee of skepticism’s integrity. When skepticism serves up opinion, it is just more noisy punditry. When skepticism can be counted on to deliver the demonstrable facts, it becomes, like Consumer Reports [or like Snopes.com], a useful public service.

For those interested in following these arguments in their original order, last week’s “’Testable Claims’ is Not a ‘Religious Exemption’” post follows immediately after this excerpt. Together they comprise the first two subsections from Part Two of “Why Is There a Skeptical Movement?”(PDF).

References

- About American Atheists.” http://www.atheists.org/about (Accessed July 28, 2011)

- “History of the Free Congregation of Sauk County: The ‘Freethinkers’ Story.” http://www.freecongregation.org/history/freethinkers-story/ (Accessed July 28, 2011)

- That event was the 1976 annual American Humanist Association conference, titled “The New Irrationalisms: Antiscience and Pseudoscience.” It took place in Buffalo, New York, April 30–May 1, 1976. Frazier, Kendrick. “From the Editor’s Seat: Thoughts on Science and Skepticism in the Twenty-First Century (Part One).” Skeptical Inquirer Vol. 25, No. 3. May/June, 2001. pp. 46–47. See also Kendrick Frazier’s history of CSICOP, which was published originally in The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal, edited by Gordon Stein (Amherst, New York: Prometheus books, 1996). Frazier was kind enough to provide me with a copy for the research of this article, but his piece has since been made available online: Frazier, Kendrick. “Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP).” 1996. http://www.csicop.org/about/csicop/ (Accessed February 12, 2013)

- Kurtz, Paul. “Introduction.” Skeptical Odysseys, Paul Kurtz ed. (Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 2001.) pp. 15–16

- For an excellent overview, see Paul, Richard. “The Critical Thinking Movement: 1970–1997: Putting the 1997 Conference into Historical Perspective.” Criticalthinking.org. http://www.criticalthinking.org/articles/documenting-history.cfm (Accessed August 15, 2011)

- Frazier, Kendrick. “From the Editor’s Seat: Thoughts on Science and Skepticism in the Twenty-First Century (Part Two).” Skeptical Inquirer Vol. 25, No. 4. July/August, 2001. p. 50

- Kurtz, Paul. “A Quarter Century of Skeptical Inquiry: My Personal Involvement.” Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 25, No. 4. July/August, 2001. p. 42

- Truzzi, Marcello. The Zetetic. Vol. 1, No. 1. Fall/Winter, 1976. pp. 5–6

- Kurtz, Paul. “The Aims of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal.” The Zetetic. Vol. 1, No. 1. Fall/Winter, 1976. pp. 6–7

- Coleman, Loren. “Is ‘Scoftic’ a Useful Term?” Cryptomundo.com. April 28, 2007. http://www.cryptomundo.com/cryptozoo-news/scoftic/ (Accessed Aug 15, 2011)

- Kurtz, Paul. “The Responsibilities of the Media and Paranormal Claims.” Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. XI, No. 4. 1985. p. 360

- Or like assholes. The “noses” version of this sentiment appears to predate the other, however.

- There was always a dissenting minority who felt that skepticism should be “widened” to tackle metaphysical claims in order to open a broader range of fire against religion, just as there are biologists who reject evolution, but this minority was traditionally very small. As folklorist Stephanie Hall found in 1999, “Most local groups now state, informally or formally, that the belief or disbelief in God is not an issue appropriate to their forum.” Hall, Stephanie A. “Folklore and the Rise of Moderation Among Organized Skeptics.” New Directions in Folklore 4.1: March, 2000. http://www.temple.edu/english/isllc/newfolk/skeptics.html (Accessed May 26, 2011)

- Shermer, Michael. “About the Skeptics Society.” Skeptic. Vol.1, No. 1. 1992. p. 50

- Shermer, Michael. How We Believe. (New York: W.H. Freeman/Owl, 2003.) pp. xiii–xv

- A word here about language. When “scientific skeptics” defend a scope of “testable claims,” these terms are shorthand. This a matter of disambiguation: what we mean is that unlike other forms of rational doubt, scientific skepticism is grounded in empiricism and informed by science. We’re after evidence; therefore, we are limited to questions on which evidence is possible, at least in principle. When we speak of “testable claims,” we do not mean we only care about questions that can tested by direct laboratory experiment (not even mainstream science is limited to experiments) but questions that are investigable through any empirical means.

- Novella, Steven and David Bloomberg. “Scientific Skepticism, CSICOP, and the Local Groups.” Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 23, No. 4. July/Aug 1999. pp. 44–46

Like Daniel Loxton’s work? Read more in the pages of Skeptic magazine. Subscribe today in print or digitally!

Your document got me excited about history, and I did a brief reading project on Marcello Truzzi, who resigned from CSICOP a year after its founding. He criticized CSICOP for, among other things, having their conclusions prior to investigation, and for pretending to be an objective judge of paranormal claims when they were really more of an advocate for one side. He founded his own magazine, Zetetic Scholar, which included both proponents and critics of paranormal in its pages.

Truzzi clearly had a different vision of the goal of skepticism, but he went in the opposite(?) direction of most critics today. Has this come up in your historical research? Do you have an opinion on where Truzzi stands in relation to the goals of skepticism discussed in this excerpt?

Yes, Truzzi is an interesting figure. I’ve touched upon his contributions from time to time, though I leave it to others to make a more thorough assessment of his legacy.

His vision of what skepticism was or could be was clearly different from the CSICOP-inspired tradition that I belong to—the tradition we call “scientific skepticism” today—but I must say that I’ve become more sympathetic to his critiques over time.

I knew Truzzi quite well, it was he who nominated me as a Fellow of CSICOP. I liked him, and we got on well. We shared an interest in opera. But having said that, I must state that Truzzi’s view of paranormal questions is quite different from skeptics like Daniel or myself, or most readers here. Truzzi always felt that there had to be ‘two sides’ to every issue, whereas a skeptic would state, with extremely high confidence, that Uri Geller does NOT have paranormal powers, or that Betty Hill was NOT abducted by a UFO. Truzzi, however, could not be sure.

Take that latter example. Truzzi participated in the classic “Encounters at Indian Head” conference in New Hampshire in September, 2000 to definitively examine the Betty and Barney Hill ‘UFO abduction’ story. It was the last time I saw him. In his chapter in the proceedings, Truzzi wrote “recent controversies initiated by postmodernists and social constructivists about scientific method and its validation process have further eroded confidence in the positivism and materialism that is characteristic of most UFO critics.” His conclusion? He was unable to decide whether or not the Hills were abducted by a UFO.

Some people see Truzzi as admirably open-minded. I see him as postmodernist and confused.

Thank you for the informative link to “Sauk County Freethinkers”. I found their history very interesting and informative. As an atheist who feels most religions have, throughout history, been nothing more than money machines at best, and a means for monarchs to further control the ignorant masses at worst, it’s refreshing to discover one like this. I doubt even the late Christopher Hitchens could have called these folks, “the evil enemy”, without blushing a bit.