Skepticism’s Oldest Debate:

A Prehistory of “DBAD” (1838–2010)

“The Amazing Meeting 9″ conference — organized skepticism's biggest, broadest, and most important meeting of the minds — is almost upon us. It seems a good moment to look back at the most widely discussed presentation at last year's TAM: astronomer Phil Plait's “Don't be a Dick” speech (video) calling for less name-calling1 and more civility in skeptical outreach:

The best idea ever thought of in the history of humanity is useless unless someone communicates it. It will die in the test tube. And in our case, what we’re communicating here to people is not necessarily something they want to hear. And so, our demeanor — how we deliver this message — takes on crucial, crucial importance.

As some readers may know, Plait's “DBAD” speech touched off an online firestorm that smolders to this day.

I explore the ethics of skepticism quite often2 (it's one of the main reasons I blog in addition to writing books and Skeptic magazine articles) but today I'd like to look at something simpler and more concrete. Let's explore a straightforward historical question:

Was Plait's call for civility something new for skepticism?

It happens that the answer is, “No, not even a little bit.” (Please note: this is a long article, running over 4500 words.)

Skepticism's Oldest Internal Debate

Immediately after Plait's speech, I began to hear suggestions that it was really a veiled attempt to protect religion, and might even have been related to some then-recent controversies over in the atheist world (controversies I won't even pretend to be able to follow).

But similar calls for a kinder, more careful skepticism predate the atheist blogosphere by almost two hundred years (as we'll see) and probably much more. They're about science-based skepticism — and during the 1980s and 1990s, they were a dominant thread in defining what we do.

Why are calls to greater civility so persistent? It's an inevitable consequence of the tension between two of skepticism's fundamental roles: criticism (which is inherently confrontational, to at least some degree) and educational outreach (which must, by its nature, reach out). The result is that calls for “More action! take the gloves off!” have always alternated with calls for a more empathetic and objective-conscious approach.

But let's leave “why” analysis for another day. For now, it's enough to look back at a small selection of skepticism's centuries of discussions about the “tone” of what we do.

Before we start, I might note in passing that I've been beating the civility drum myself for years. (For recent examples, consider my 2009 discussion about civility with Maria Walters and MonsterTalk's Blake Smith on the Skepchick podcast, or the “Don't Call People Names” section of my What Do I Do Next? activism panel PDF. Those were hard-won lessons from my work critiquing cryptozoology and paranormal claims, and had nothing to do with religion.)

But you already knew I promote this stuff. Let's look at what others have said.

Do note that this is no sense an exhaustive literature review. These are just the first few examples that came to mind. Even at that, I'm passing right by most of the recent work related to this theme, including such offerings as Rebecca Watson's 2010 “Don't Be a Dick: Etiquette for Atheists and Skeptics” presentation (in which she urged, “Do whatever it takes to recognize that the person you're talking to is a human”) and the short-lived podcast Actually Speaking (which aimed to explore “the Human Side of Skepticism”). As well, note that this is explicitly intended as an introduction to one prominent school of thought within scientific skepticism; the other side of the pendulum will have to wait for another post. Finally, note that I am leaving aside similar discussions within many other spheres (such as atheism, politics, online gaming, and the wider blogosphere).

Skeptical Appeals to Civility Before DBAD

2010

The most amusingly exact “Don't Be a Dick” parallel must be “Don't Be a Jerk!” — an article that Ottawa Skeptics president Jonathan Abrams wrote just months before Plait's speech. “When countering a claim,” Abrams urged, “try as hard as you can to avoid making the disagreement personal. Be humble, admit that you can be wrong too, but most importantly: don’t be a jerk.”

2008

Abrams in turn was inspired by Skepticblog's own Brian Dunning, who in 2008 explored “How to Be a Skeptic and Still Have Friends.”

Spreading critical thinking by engaging in conversation with your acquaintances should be a way to build bridges, not to expose rifts. If you take one thing away from this podcast, it should be that point. Concentrate on where you agree. I've found that this has converted people who used to come to me as an adversary to challenge me with new claims into friends who seek out my opinion on stories that sound fishy to them.

2004

McLaren's article appeared in Skeptical Inquirer Vol. 28, No 3 (2004)

A significant milestone was a 2004 Skeptical Inquirer article titled “Bridging the Chasm Between Two Cultures.” Written by a former New Age author named Karla McLaren who had become involved in the skeptical community,3 this moving piece shared an audience perspective that skeptics needed to hear.

Why do I have to type the word “quack” when I want a skeptical review of the choices I make in medical care? And why do I have to spend so much time translating on the skeptical sites I visit — or just skipping over words like scam, sham, quack, fraud, dupe, and fool? Why do I (the sort of person who actually needs skeptical information) have to see myself described in offensive terms and bow my head in shame before I can truly access the information available in your culture?

Good question. I was riveted by this article.

McLaren highlighted a critical, systematic flaw in skeptical outreach and skeptical media: it's designed by skeptics, and its success is measured by the approval of other skeptics. Our sometimes life-saving information seems almost intentionally packaged to appeal to the tiny minority of people who don't need it — and to repulse the majority,4 who do. (As Phil Plait's DBAD speech put it, “Look, we have to admit that our reputation amongst the majority of the population is not exactly stellar.”)

Closely echoing Carl Sagan, McLaren emphasized that “the search for the truth, the concern for the welfare of others, the need to be treated with respect, and the need to be welcomed in a culture — are all things my people share with yours.” She pleaded for bridges: smart, welcoming attempts to genuinely communicate with those who needed it most.

But none of this stuff was new to the 2000s. Not at all.

1999Consider the movement as it was described in folklorist Stephanie Hall's 1999 paper, “Folklore and the Rise of Moderation Among Organized Skeptics.” Her analysis of the movement at that time sounds very different from the situation today, but it's consistent with my own memories. During the 1990s, limited-scope “scientific skepticism” was dominant among local, regional, and national skeptics groups; and, through the influence of astronomer Carl Sagan (almost certainly the most widely admired public voice for scientific skepticism) a trend was leading skeptics further away from fiery, adversarial, authoritarian rhetoric.

Sagan's DBAD Arguments

1996

Carl Sagan was involved with the first successful North American skeptical group (CSICOP, now called CSI) from its formation in 1976. But his involvement with skeptical activism went back even further — and, amusingly, his first act was to object to the “tone” of a skeptical project.

Carl Sagan was involved with the first successful North American skeptical group (CSICOP, now called CSI) from its formation in 1976. But his involvement with skeptical activism went back even further — and, amusingly, his first act was to object to the “tone” of a skeptical project.

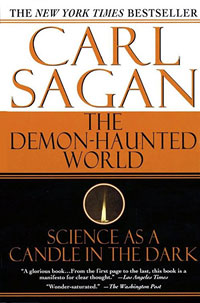

It was a case that mattered so much to him that he was still talking about it 20 years later. As Sagan recalled in the 1996 book The Demon-Haunted World (in my opinion, the finest skeptical book ever written),

In the middle 1970s an astronomer I admire put together a modest manifesto called “Objections to Astrology” and asked me to endorse it. I struggled with his wording, and in the end found myself unable to sign — not because I thought astrology has any validity whatever, but because I felt (and still feel) that the tone of the statement was authoritarian.5

I invite you to read “Objections to Astrology” for yourself before we go on. (It's short. We'll wait.) You'll notice that it's mild by the standards of the blogosphere, and not too dissimilar to current skeptical projects (such as the “10:23″ campaign against homeopathy). So what was Sagan's problem with the statement, which was, after all, signed by multiple Nobel Prize-winners?

The statement denounced what it called “the pretentious claims of astrological charlatans,” but it failed to make a serious, science-based case in support of this opinion. “What I would have signed,” Sagan reflected, “is a statement describing and refuting the principal tenets of astrological belief.”

Instead, he felt, this “stuffy dismissal by a gaggle of scientists” simply decreed that astrology is stupid. “It criticized astrology,” Sagan noted, “for having origins shrouded in superstition” — but so do many legitimate sciences. So what? The question is whether it works. Sagan went on:

Then there was speculation on the psychological motivations of those who believe in astrology. These motivations — for example, the feeling of powerlessness in a complex, troublesome and unpredictable world — might explain why astrology is not generally given the skeptical scrutiny it deserves, but is quite peripheral to whether it works.

The statement stressed that we can think of no mechanism by which astrology could work. This is certainly a relevant point but by itself it’s unconvincing.

(Lots of true things were known to be true long before we knew why they were true.)

Sagan's arguments about tone were widely taken to heart, and helped to define the skepticism of the 1990s. In particular, it would be difficult to overstate the influence of The Demon-Haunted World, which explicitly acknowledged the tone problem:

Have I ever heard a skeptic wax superior and contemptuous? Certainly. I've even sometimes heard, to my retrospective dismay, that unpleasant tone in my own voice. … In the way that skepticism is sometimes applied to issues of public concern, there is a tendency to belittle, to condescend, to ignore the fact, that, deluded or not, supporters of superstitions and pseudoscience are human beings with real beliefs, who, like the skeptics, are trying to figure out how the world works and what our role in it might be. Their motives are in many cases consonant with science. If their culture has not given them all the tools they need to pursue this great quest, let us temper our criticism with kindness. None of us comes fully equipped.6

Note that Sagan's criticism was in every meaningful way identical to the arguments of Phil Plait's DBAD speech. Sagan wrote,

And yet, the chief deficiency I see in the skeptical movement is in its polarization: Us vs. Them — the sense that we have a monopoly on the truth; that those other people who believe in all these stupid doctrines are morons; that if you’re sensible, you’ll listen to us; and if not, you’re beyond redemption. This is unconstructive. It does not get the message across. It condemns the skeptics to permanent minority status; whereas, a compassionate approach that from the beginning acknowledges the human roots of pseudoscience and superstition might be much more widely accepted.7

Good Old Common Sense

1992

It's sometimes said that skepticism has no handbook; but skeptical investigation, at least, has more than one. These include Missing Pieces—How to Investigate Ghosts, UFOs, Psychics, & Other Mysteries, by Robert Baker and Joe Nickell; and, Ben Radford's recent Scientific Paranormal Investigation: How to Solve Unexplained Mysteries.

As a practical guide, Nickell and Baker's 1992 book is of course packed with practical advice. Empathy and courtesy are emphasized throughout as best practices. This passage (under the section heading “Some Ethical Issues”) is particularly blunt.

You can avoid ethical dilemmas most of the time by using your good old common sense and good judgement. If you would do more harm to people by ridiculing their religious beliefs than by allowing them to keep them and yet help them solve their immediate problem, you leave their beliefs alone and help them solve their pressing problem. This is the only ethical thing to do. Zealotry, whether on the part of a skeptic or on the part of a psychic is equally deplorable.8

Nor was restraint simply a matter of compassion, according to Missing Pieces, but of responsibility.

Unfortunately, many times in the years past zealous skeptics have often displayed more emotion than logic, made sweeping charges that the evidence failed to support, failed to document their assertions, and generally did not do what was necessary to make their challenges credible. Such ill-considered criticism can do much more harm than good.9

Their advice? Follow the steps outlined by psychologist Ray Hyman in his article “Proper Criticism” (which we'll come to shortly) — especially “the principle of charity.”

Not to Scorn Human Actions, But to Understand Them

1992

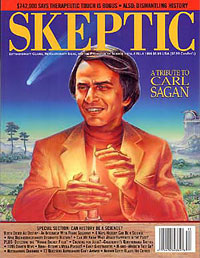

Founded in 1992, Skeptic magazine was inspired by the example of Carl Sagan — and it's been an explicitly tone-conscious project since day one. Michael Shermer is well-known for his exploration of why smart people believe weird things (a theme he takes up once again his 2011 book The Believing Brain); it's no surprise that he and Pat Linse decided to promote this Spinoza maxim as the message at the heart of the Skeptics Society:

I have made a ceaseless effort not to ridicule, not to bewail, not to scorn human actions, but to understand them.

Reflecting on this motto, Skeptic co-publisher Pat Linse recalls,

When I worked a cash register, one of the best indications that I was about to be handed a bad check was an aggressive attitude on the part of the customer. It's the same with a discussion. One of the best indicators of a weak argument is aggression on the part of the person making it.10

Moreover, as Michael Shermer emphasizes,

If you start off a conversation with people by telling them that their most cherished and committed beliefs are utter nonsense and bullshit you have just ended the conversation before it even began — and shut the door to any further communication about the virtues of skepticism.11

These sentiments are built into his lectures, but it isn't just talk. Shermer has held fast to the calm, truth-seeking approach even in the face of enormous pressure, and even when his temptation might have been to judge first, and understand later.

On March 14, 1994, Shermer appeared on The Phil Donahue Show (a ratings powerhouse that pioneered the daytime talk genre later dominated by Oprah) to refute the claims of Holocaust deniers Bradley Smith and David Cole. (Video.) Shermer recalled what transpired during a commercial break between debate segments:

Thinking that I had done fairly well in analyzing the methodologies of the deniers, I was comfortably awaiting the next segment when the producer came running over to me. “Shermer, what are you doing? What are you doing? You need to be more aggressive. My boss is furious. Come on!” I was shocked. Apparently either Donahue thought the Holocaust deniers could be refuted in a matter of minutes, or he was hoping I would just call them antisemites as he did and be done with it.12

Shermer certainly defended legitimate history, and he critiqued the revisionists' arguments; but, he did not veer off into personal attacks. Instead, he actually agreed on camera with some of the claims made by the Holocaust deniers — because those particular claims happened to be true. Any guesses to whether he enjoyed being in that position? The answer is that it doesn't matter: Shermer's a skeptic and historian. The truth is supposed to come first.

Researching for their 2000 book Denying History, co-authors Michael Shermer and Alex Grobman rejected professional criticisms that it was improper for them to have cordial meetings with Holocaust deniers.

When dealing with the claims of the Holocaust deniers, we believe it is not enough to be ivory-tower academics, attempting to achieve objectivity with distance, when the individuals who make these claims are friendly, eager to talk, and merely a phone call or plane ride away. …

Primary sources are the most important tool of the historian, and what could be more primary in writing a book about Holocaust denial than meeting the deniers themselves, seeing their offices, asking them questions, reading their literature, and, in general, trying to get inside their minds?13

This is a little-appreciated aspect to the issue of tone: the research advantage of collegiality. When skeptics treat opponents with courtesy, we are better positioned to acquire the understanding we need to be well-informed and effective critics.14 During Shermer's Donahue adventure, the host soon found himself in over his head because he lacked specific expertise about Holocaust revisionism. This can easily happen to skeptics who decline to have conversations across deep, deep ideological divides.

The Darker Side of Ridicule

Critics often frame civility debates as a dichotomy: exercise restraint, or be honest. But skeptics long ago learned that the choice is just as often between honest restraint and making stuff up. That is, incivility sometimes goes hand in hand with exaggeration, factual inaccuracy, and legal liability. (Consider such common skeptical phrases as “He's a fraud.” It's always insulting, but it's only occasionally true.)

1991

Skeptic Jim Lippard tackled this in his 1991 article “How Not To Argue With Creationists,” published in the National Center for Science Education's journal Creation/Evolution. According to Lippard, “opponents of creationism in Australia have engaged in tactics that have led to public apologies to creationists by radio and print media, criticism by other creationism opponents, and even legal action.” He provided several detailed case studies, which I urge skeptics to read.

For example, Lippard was critical of what he called the “false statements” of Ian Plimer, who was among the most scathing opponents of creationism. (Plimer is best known to skeptics today for his intensely disputed attacks against climate science.) Lippard cited cases in which Plimer made serious allegations about financial wrongdoing on the part of creationist organizations — allegations for which the Australian Broadcasting Company and the journal Media Information Australia15 later apologized.

Lippard also quoted from a letter in which Plimer wrote of “an entourage of young people (principally boys) accompanying [creationist Duane] Gish and who continually touched him. This is commensurate with testimony from elsewhere which throws enlightenment on Gish's personal life and which makes Jimmy Swaggart look like a moral guardian of the faith.” Lippard concluded that this allegation was “unsupported ad hominem innuendo.” (Gish himself called it “an outrageous slanderous falsehood,” saying “I defy Plimer to produce one iota of evidence to support the above accusation.”)

Note that Lippard's arguments for “a more careful style of debate and dispute” were pragmatic:

Ian Plimer and others have defended his style on the grounds that creationism is a political rather than scientific movement. It is my impression that they think it must be stopped at any cost, by almost any means available. … While the heavy-handed style might convince some people that creationism is ridiculous and not worth serious consideration by scientists, misrepresentations are bound to come to light (as they have). When they do, all of the short-term gains and more are lost.

We must not lose sight of the fact that no matter how silly creationism looks from an informed perspective, those who adhere to it are human beings. … Ridicule and abuse simply confirm their suspicions about evil conspiratorial evolutionists who are out to suppress the creationist viewpoint.16

Lippard was not, incidentally, the first science advocate to express concern about Plimer's approach. In 1989, David Suzuki used Plimer as an example for his criticism that “some evolutionists have become zealots in their pursuit of truth, as rancorous as their targets.”17

Looking back, Lippard offered a simple conclusion: “opponents of creationism should not use the same tactics that creationists often use; they should be careful, honest, and accurate.”

(It's not directly related, but Plimer later took his battle against creationism to court — and reportedly wound up with an order to pay half a million dollars in court costs.)

Proper Criticism

1987

Psychologist Ray Hyman, 2003. Photo by Rouven Schäfer; provided by Barry Karr

This brings us to what may be the most concise and valuable argument for skeptical restraint ever advanced: a 1987 article entitled “Proper Criticism,” written by psychologist Ray Hyman (another CSICOP founder). According to CSI Executive Director Barry Karr, Hyman's “Proper Criticism” is “probably the most reprinted and widely disseminated item to ever appear in the Skeptical Inquirer or Skeptical Briefs,” being widely adopted and reprinted by skeptical organizations across the United States — and worldwide.18

“Proper Criticism” came at the end of the skeptical movement's infancy, after a decade spent learning the hard lesson that, as Hyman put it, “the critic’s task, if it is to be carried out properly, is both challenging and loaded with unanticipated hazards.”

What hazards? Lawsuits were on Hyman's list (not unreasonably: James Randi and CSICOP soon wound up facing a $15-million dollar defamation suit — an ever-present threat that can bring skeptics to ruin today). Wastefulness was another:

During CSICOP’s first decade of existence, members of the Executive Council often found themselves devoting most of their available time to damage control — precipitated by the careless remarks of fellow skeptics — instead of toward the common cause of explaining the skeptical agenda.19

But Hyman was most concerned about integrity.

We can make enormous improvements in our collective and individual efforts by simply trying to adhere to those standards that we profess to admire and that we believe that many peddlers of the paranormal violate. If we envision ourselves as the champions of rationality, science, and objectivity, then we ought to display these very same qualities in our criticism. Just by trying to speak and write in the spirit of precision, science, logic, and rationality…we would raise the quality of our critiques by at least one order of magnitude.

Hyman had concrete suggestions about how to accomplish this, discussed under these subheadings:

- Be prepared.

- Clarify your objectives.

- Do your homework.

- Do not go beyond your level of competence.

- Let the facts speak for themselves.

- Be precise.

- Use the principle of charity.

- Avoid loaded words and sensationalism.

(You'll notice that this quarter-century-old list covers the exact same ground as the two most challenging speeches at 2010's TAM8 conference: Plait's DBAD speech, and Massimo Pigliucci's warning to skeptics about the hubris of opining outside our expertise.)

Of these principles, Hyman anticipated that the “principle of charity” might be the most controversial.

I know that many of my fellow critics will find this principle to be unpalatable. To some, the paranormalists are the “enemy,” and it seems inconsistent to lean over backward to give them the benefit of the doubt. But being charitable to paranormal claims is simply the other side of being honest and fair.

This is functionally equivalent to Steven Novella's “fair engagement” or Wikipedia's “Assume good faith”: do make a genuine effort to understand your opponent's best case, and engage with that; don't assume wicked motives that aren't in evidence. As Hyman went on,

We often can challenge the accuracy or validity of a given paranormal claim. But rarely are we in a position to know if the claimant is deliberately lying or is self-deceived. Furthermore, we often have a choice in how to interpret or represent an opponent’s arguments. The principle tell us to convey the opponent’s position in a fair, objective, and non-emotional manner.

This, says Barry Karr, “provides a necessary reminder that we are in the business of examining claims and criticizing ideas, not the person. Yes, we can be firm in our objections, but above all we must be fair and honest in our approach.”

CSI's Executive Council continues to wrestle with thorny ethical issues, in which Hyman and his thinking remain guiding lights. As Kendrick Frazier (Editor of the Skeptical Inquirer for the past 34 years) explains,

“Proper Criticism” is and has been a leading ethical and strategic guide for skeptics. It is important especially for the new generation of skeptics to read and heed it. It gives a sense of the disputes older skeptics have gone through, how to avoid them, and, most important, how to be effective.20

An Early Schism

1977

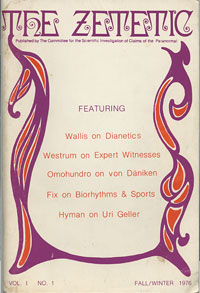

Truzzi was the original Editor of The Zetetic, which was retitled Skeptical Inquirer for its third issue.

Sociologist Marcello Truzzi was a founding member of CSICOP (indeed, CSICOP was built on top of a fledgling group Truzzi started in 1975), and the first Editor of its journal, The Zetetic (now called Skeptical Inquirer). He resigned that role after only two issues over differences of principle — including the linked issues of tone and open-mindedness.

Commenting on Truzzi's resignation, the journal Science summed up the disagreement:

There is thus a spectrum of opinion on the committee between those who tend to favor a harder-line, debunking treatment of the paranormal and those who tend toward a skeptical but open-minded assessment of paranormal claims. The “debunkers” wish to deploy the full power of the scientific method against paranormal beliefs; the “skeptics” consider that such prejudgment of paranormal claims is as unscientific as some of the claims may be themselves.21

Ray Hyman is quoted in this same Science article, expressing a sentiment that foreshadows his “Proper Criticism” article of 10 years later:

People with a background in magic…tend to see this as a crusade for people’s minds, in which we should fight fire with fire, and not get too subtle or scholarly or we will lose by default. I believe we would be more effective by being more scholarly and building up our credibility.

Truzzi went on to write decades of critiques of organized skepticism, and landed some palpable hits. (His 1987 article “On Pseudo-Skepticism” is essentially identical in content to my recent “Climbing Heinlein's Hill”). Still, I remain unpersuaded by his general disdain for CSICOP-style skepticism. A devil's advocate, after all, tells only half of any story. Either way, Truzzi was a pivotal figure in creating the English-speaking skeptics movement: he helped create the first North American skeptical groups; he was the original Editor of the first North American skeptics publication; and, he is credited with coining the phase “An extraordinary claim requires extraordinary proof” (most famous in the modified form later used by Sagan, though the sentiment predates both).22

And there at the very beginning: a battle over tone.

Unwept, Unhonoured, and Unsung

1838

And yet, skepticism's tone arguments predate even the founding of the first skeptical organizations. They predate television, airplanes, and electric light bulbs.

Long before the invention of Bigfoot, or flying saucers, or chiropractic, or spiritualism, or “psychical research,” skeptics were making impassioned appeals to other skeptics about tone.

I'll close today with a lengthy quote from the 1838 book Humbugs of New York.

It really says it all.

Unhappily, however, those who have buckled on the armour against the follies of the times, have been often unwise and indiscreet in the character and spirit of their measures. Disgusted by the stupidity of the victims of delusion, and provoked by their obstinate adhesion to error, they have assailed them personally, instead of attacking the false philosophy and pseudo-philanthropy by which they have been imposed upon; and thus they have made a show of intolerance which has been fatal to their success. …

Persecution only serves to propagate new theories, whether of philosophy or religion, as the history of the world demonstrates; and this it has never failed to do, whether those theories were true or false. They acquire fresh vigour under the blows of intolerance, and like vivacious insects seem to multiply by dissection. Hence, every attempt to put down impostors, or enthusiasts, by censoriousness and invective, directed against them personally, because of their follies or their crimes, has ever been unsuccessful. They are themselves so sensible that opposition of this kind promotes their cause, that they desire, invite, and even provoke it. Indeed some of the popular follies of the times are indebted solely to the real or alleged persecutions they have suffered, not only for the number of their votaries, but even for their present existence; and but for this they would long since have descended to the tomb of the capulets, “unwept, unhonoured, and unsung.”23

References:

- Plait borrowed the “don't be a dick” phrase from an existing internet maxim, Wheaton's Law, and included it near the end of his speech as a rhetorical flourish. His argument could have been made without it (as, indeed, Carl Sagan did in 1996). Was it predictable that “Phil's calling us dicks!” would come to dominate the discussion, in many cases pushing Plait's arguments aside? Probably. It's unfortunate that this was the result, but it actually goes to Plait's point. When people feel insulted, the insult becomes the discussion.

- See (among others) my posts “Horse-Laughs, the Rapture, and Ticking Bombs”; “Skeptics as Model Train Lovers (Part II)”; “The Reasonableness of Weird Things”; or, “Bring on the Science of Honey and Vinegar.”

- “I'm not just a member of the New Age community,” McLaren emphasized. “I've also been a purveyor of the very things the skeptical community is so concerned about. I've been involved in metaphysics and the New Age for over thirty years, I've written four books and recorded five audio learning sets in the genre, and I was considered one of the leaders in the field.” Her earlier books include such titles as Your Aura & Your Chakras: The Owner's Manual. (Her recent book The Language of Emotions emphasizes social science while continuing in a self-help vein.) Much has been made about her journey to skepticism, but it's her insight into the New Age culture that is useful to this “tone” discussion.

- As Michael Shermer notes in his post “The Demographics of Belief,” “Although the specific percentages of belief in the supernatural and the paranormal across countries and decades varies slightly, the numbers remain fairly consistent that the majority of people hold some form of paranormal or supernatural belief.”

- Sagan, Carl. The Demon-Haunted World. (Random House: New York, 1996.) p. 302

- ibid. p. 297–298

- ibid. p. 300

- Baker, Robert and Joe Nickell. Missing Pieces: How to Investigate Ghosts, UFOs, Psychics, & Other Mysteries. (Prometheus Books: Buffalo, New York, 1992.) p. 298

- ibid. p. 286. This passage is borrowed with little modification from the Ray Hyman article they were discussing.

- Personal communication from Pat Linse. June 16, 2011

- Personal communication from Michael Shermer. June 20, 2011

- Shermer, Michael. Why People Believe Weird Things. (W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, 1997.) p. 179

- Shermer, Michael, and Alex Grobman. Denying History. (University of California Press: California, 2002.) p. 2

- Skepticism's classic case is the “pleasant acquaintance” between Harry Houdini (a relentless debunker of spirit mediums) and Ira Davenport (the surviving half of “The Davenport Brothers,” who were superstar pioneers of spirit mediumship). Davenport revealed to Houdini “much of historical value concerning the brothers which has never appeared in print”—which is to say, exactly how they did it. While all previous accounts of the brothers had been “vague, speculative, lacking in knowledge,” Houdini was the only investigator to get Ira's “open hearted confession.” Houdini, Harry. A Magician Among the Spirits. (Fredonia Books: Amsterdam, 2002.) p. 17–37

- “Apology to Creation Science Foundation Ltd.” Media Information Australia. No. 55. February 1990. p. 64. “…Media Information Australia wish to advise that the views and allegations contained in the above article are those of Professor Plimer and are not adopted or shared by the Australian Film, Television & Radio School, its officers, servants and agents or the editors and others involved with the publication of Media lnformation Australia. Any harm that has been suffered by the Creation Science Foundation Ltd and its Directors and other officers and members and Duane T Gish is apologized for and regretted.”

- Lippard, Jim. “How Not to Argue With Creationists.” Creation / Evolution. Vol. 11, No. 2 (Winter 1991–1992.) p. 9–21. Full issue PDF. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- Suzuki, David. “Creationism Flourishes in North America.” The Lethbridge Herald, Dec 16, 1989. p. 6

- Personal communication from Barry Karr. June 20, 2011

- Hyman, Ray. “Proper Criticism.” Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 25, No. 4. July / August 2001. p. 53–55.

- Personal communication from Kendrick Frazier. June 20, 2011

- Wade, Nicholas. “Schism Among Psychic-Watchers.” Science 197. 1977. p. 1344

- Earlier articulations of this sentiment also exist; notably, David Hume's maxim, “A wise man, therefore, proportions his belief to the evidence.” Hume, David. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. (Open Court Publishing Company: Peru, illinois, 1993.) p. 144

- Reese, David Meredith. Humbugs of New York: being a remonstrance against popular delusion. (New York: 1838.) p. 14–16.

Like Daniel Loxton’s work? Read more in the pages of Skeptic magazine. Subscribe today in print or digitally!

Lox, you are a scrivening wildman.

There’s also a long history of major figures in the movement arguing the other side of this debate too.

Yeah, but they’re a bunch of dicks.

Guess I wasn’t the only one to notice that this history of the “tone” debate was rather one-sided.

That was the entire point of the essay – a history of calls for civility. If you’re wanting to write a history of calls for ‘the other side’, I don’t think anybody’s stopping you. In fact it might make for interesting reading to get a historical perspective on these major figures who call for ridicule, name calling or a general inflammatory approach.

I suppose you take the question “Was Plait’s call for civility something new for skepticism?” as the topic of the essay. This appears to be reasonable. However, most of the article isn’t just about answering this question. After all, the Humbugs of New York quote alone would have established its answer.

Instead, I took this as being the main point of the essay: “For now, it’s enough to look back at a small selection of skepticism’s centuries of discussions about the “tone” of what we do.” This sentence is clearly meant to summarize what follows. However, it promises more than is delivered, as we’re only getting one half of the discussion.

Besides, its not clear to me what the goal of this essay is. It can’t be to persuade the readers that the call for civility is not new, as that has never been in contention, as far as I’m aware. Or its goal could have been to persuade the readers of the correctness of the “civility” position, but in that case it would be little more than one big argument from authority and tradition. The principle of charitable interpretation would therefore lead me to assume that the purpose was to provide historical context to the “civility” debate – but in that case I would definitely expect a less one-sided treatment.

For these reasons, I think it was a disappointing essay.

Actually, it *has* been in question. There was a strong theme running through post-DBAD comments suggesting that the “tone wars” were in fact a response to the expanding role of atheist activists over the past decade, i.e., an attempt to regain a privileged position for religion among supernatural claims.

I can’t directly speak to my brother’s intentions (we discuss these things only periodically, and often have differing opinions), but the purpose of this essay seems clearly to be (consistent with his stated goal in the introduction): 1) to falsify the new religious coddling claim, 2) to provide a contextual history of the many iterations of *a particular argument* (hence the subtitle: “A prehistory of DBAD”), and 3) to provide a set of references to the *substance* of these past statements in support of this position, i.e., Hyman’s seminal paper, which many new to skepticism are likely unfamiliar with (there’s a lot of reinventing the wheel going on in these Internet flame wars).

I’ve added a few words of further clarification:

@Jason Loxton:

But this essay doesn’t refute this possibility at all. The fact that the tone wars have been going on for centuries doesn’t say anything about the reasons why Phil Plait decided to fire a new volley at that particular moment. “New Atheism” may very well have had something to do with that. Is there any doubt that New Atheism has been causing a lot of discussion about “tone” in the skeptic community lately?

@Daniel Loxton: thanks for the clarification. The essay seems to do a fine job at accomplishing that goal. But in that case, it might have been better to not link it to the DBAD speech at all. The essay still fails at providing context for DBAD, because you still explicitly refuse to discuss a large portion of the context that made it controversial (i.e. atheism). And it fails at defending DBAD from its critics because it fails to engage with their arguments. Otherwise, I liked the references and the links, and they contain some good advice, but I hope you can at least understand why I was still disappointed.

That’s quite the journey through recent history.

When in doubt, I just keep reminding myself: Fluffy kittens are good.

Wow, it is quite obvious looking at the comments who actually pays attention and who really enjoys missing the point.

Much like the reactions to Plait’s speech.

Along with that, Derek, beyond a “Deen,” the PZs and Coynes, and Pharyngulacs and Coyneheads, will likely have the same reactions as after Phil’s speech. It’s always “the other side’s fault.”

Eventually, I think of Einstein’s insanity comment.

Beyond that, and how this controversy within skepticism overlaps with the Gnu Atheism issues …

I think the word “empiricist” is better than either “skeptic” or “atheist.”

Plenty right in falling back on good old David Hume.

What happened to “7.Use the principle of charity.”?

I, for one, was raised in a very religious household where Carl Sagan was viewed as a bad person (I still, to this day, am not sure what the reasoning for that was as a side-note). I am a self-made skeptic in that I never knew of the movement or philosphy until after I already started thinking this way. As such, I was not familiar with pretty much anything prior to DBAD so I would just like to thank Daniel for a great article.

The SGU was my window into the skeptic movement, and I’ve always admired Steven Novella for the manner in which he communicates. It’s a treat for me to see a lot of the likely sources behind his approach.

Though I don’t have the same upbringing (family didn’t attend church, but generally believed in God), I found my way to the skeptical movement in almost the same fashion. I fully agree with you regarding Dr. Novella, and I comment to myself all the time that if only I could communicate in the same fashion, I’d get my points across so much more effectively when I debate people like creationists, CAM-believers, etc.

Daniel, I’d be curious to hear your take on the appointment of Dr. Laura to the Skeptic board of advisors in 1994, and her subsequent resignation, in light of DBAD. The case seems similar in nature to some of the recent disputes about individuals that do good work within the community, but are still vocal about their irrational beliefs.

After I wrote this comment it now seems like a troll, sorry. Feel free to remove – although I’d love to have the conversation with you sometime.

Brian: IMHO, inviting Laura Schlessinger to the Skeptic magazine editorial board was a mistake–I had never heard of her before, at the time, so I’m not sure how well her reputation for obnoxiousness was known. She resigned after _Skeptic_’s “God” issue came out. (Richard Abanes, an evangelical Christian, is still on the Skeptic editorial board…)

“incivility sometimes goes hand in hand with exaggeration, factual inaccuracy, and legal liability.”

This is a part of the tone debate that gets overlooked far too often.

That’s the most important part, to my mind. Civility is generally a good thing, but more important is having consistent standards, charitably interpreting arguments of opponents and dealing with the strongest versions of their positions, and fairly dealing with evidence.

I think Daniel’s blog post is another salvo in an ongoing social negotiation over the identity of the skeptical movement which involves more than tone–it also involves scope and definition. I am an advocate of civility, but sometimes arguments about civility and tone are used as an excuse to silence or exclude. My idea of a healthy skeptical movement is one which promotes a culture of internal criticism in a civil manner, which avoids double standards, which calls out skeptics for doing things that a believer would be blasted for.

You’re quite right. As this post touches on, skepticism’s “civility” arguments contain a portfolio of related issues, including outreach efficacy, quality of scholarship, the role of opinion, and the question of traditional scientific scope versus wider rationalism.

Ah, if only you accommodationists would apply that standard to yourselves.

The whole “tone” argument is a dismissive attempt by some timid skeptics to tar others with a lack of those good qualities of consistent standards and dealing with the evidence. The accusation that one is a dick isn’t used to just argue that one should be nicer; it’s a dog-whistle implication that one isn’t dealing fairly with the evidence.

It’s also a rat-hole to hide in. Whining about “tone” is a familiar tactic to shut down provocative debate.

Although I completely disagree with your accusation that the pleas for civility are insincere, I’ll concede that the most recent arguments often include pointing out that opposing arguments have been lacking in supporting evidence and often evade questions of effectiveness.

If by “provocative” you mean the kind of debate that involves ridicule, ad hominem attacks, and appeals to emotion rather than reason and compassion, then “be civil” certainly does exclude “provocative debate”. Such “fights” may be attention-grabbers; they may sell books or increase hits to a blog, but they are usually polarizing and counterproductive.

I think it all comes down to the question of goals.

Sure. You’re right. It can be that. But, sometimes fairly so. (See Jim Lipard’s comments below re: the relationship between tone and hyperbole/unfair representation.)

An example: As research scientists working on evolutionary issues, and as science educators, you and I both spend far too much of our time dealing with creationist crap. It is tempting to give in and say things like (and this isn’t in reference to you, but to another scientist I respect that I was reading recently) (paraphrasing): “These guys are all a bunch of lying idiots, and none of them know a thing about biology or geology! They’ve never set foot in a lab, and they’ve never looked at an outcrop!”

That statement is simple and powerful, but also untrue on every level (at least when applied to creationists as a inclusive group–take Steve Austin as an example, he’s a creationist geologist who gets in the field and presents at meetings; I don’t understand him, but his opinions aren’t for lack of exposure to rocks).

In this case, an alternative, tactful (“wishy-washy”) statement like: “Creationists are a mixed bag, and their motivations are similarly mixed. Many are well-intentioned, and some even have relevant advanced degrees in biology, paleontology, geology, etc., but their conclusions are at odds with those of nearly all qualified scientists working in these fields, from all religious and cultural backgrounds. Their positions are out of keeping with mainstream science, and have been so in many cases for nearly 200 years” is both nicer, and more accurate.

Again, it obviously can be. But, in this post, and in his previous posts, Dan is clearly calling for both more dialogue and data/historical reflection. I don’t think this statement is on mark here.

There’s no “dog-whistle” here: I explicitly state in this post that “incivility sometimes goes hand in hand with exaggeration, factual inaccuracy, and legal liability.” (As evidence that this sometimes happens, the article cites Lippard’s case studies of firebrands making apparently unsupportable statements.)

I write for children. “Whining about ‘tone'” is the one thing I do that is absolutely guaranteed to increase “provocative debate.”

You “explicitly state”? No, you don’t. As with Plait’s talk, you explicitly state nothing: no examples, no specific problems, just a blanket dismissal of some vaguely defined bad people out there, somewhere.

Apparently, with civility also comes exaggeration and inaccuracy.

That was a quote from the article, PZ.

And, again, I directly cite and describe Lippard’s very specific examples.

So…all of this finger-wagging is directed at Ian Plimer and a few others from 1991?

Glad to see you’re staying current.

This post was written and promoted as a historical piece. It contains historical examples.

And that implication is sometimes absolutely correct. I remember when you completely misrepresented someone’s argument and called someone a “witless wanker” based on that misrepresentation. Worse, when a complaint was raised on both your tone and content, you falsely claimed that the “entire complaint is about goddamned tone.” Hint: When one of the paragraphs in a complaint begins with “Wow, I counted at least four gross mistakes in just this one paragraph,” that’s a sign that your content is being judged.

This is not even the only instance where you’ve crossed the line into factual distortion.

In the battle between the De Dora and the Myers that you sketch, I’m on De Dora’s side. But I’ve read the referenced writings of the real De Dora and Myers, and there I’m on Myers’ side.

Ms. Bunfield, I don’t want to belabor the point (especially since looking back, my earlier post probably pushes the bounds of the comment policy), but when an article (DeDora’s) states,

and

then it’s pretty hard to justify the claims by PZ Myers that the article supports allowing creationist answers to be scored correct on a test.

Mr. Ramsey, you take little bits of the original articles out of context. Yes, in the bit of the DeDora’s article that you cite, he argues for teaching evolution. But in the rest of the article he says that that scientific facts that follow from it cannot be taught if they contravene religion. Claiming irrelevance doesn’t work, given the milieu of birth of this corner stone of natural history.

And the bit of Myers’ blog post you site (and perhaps the comic) is perhaps hyperbole, but functional, appropriate hyperbole in my opinion. When you hold that creationism cannot be criticised in the classroom, what do you do when someone fills in ‘6000 years’ in response to a test question? A red slash is criticism, I’m afraid. I also find it worrying that De Dora argues that criticism of 2 + 2 = 5 is allowed, because it is not a religious view. If it were, it would still be wrong, wouldn’t it?

Since this is just a quick response to your message, it will necessarily and unfortunately biased in the opposite direction; the real De Dora and Myers are more nuanced than this. But in any case, I think your writing turns both people into caricatures of themselves.

The absence of a quote in support of that claim is noted.

Furthermore, DeDora pointing out that “courts simply will not rule that biology classes are unconstitutional because they teach children about biology, no matter the implications of gained knowledge” directly contradicts your claim. If facts are taught in a public school classroom and they happen to contradict someone’s religion, that’s not the public school’s problem. Going out of the way to criticize specific religions is where a church-state problem comes it. BTW, that’s actually case law.

Well, real PZ, or fake PZ, if you want an incivil tone … you’re full of crap.

If you want specifics:

1. Bad standards? First, you want to “purge” conservatives from the atheist movement. (I didn’t know it was a movement. That, of course, overlooks that atheism isn’t political liberalism.

2. You then try to claim (laughs!) Sam Harris isn’t a conservative? Really? Favorably referencing a neocon Zionist by name in The IMmoral Landscape as part of his Islamophobia, along with his call for extrajudicial killings, isn’t conservative?

2A. Ergo, you don’t want to consider him conservative so you don’t have to “purge” him.

http://socraticgadfly.blogspot.com/2011/06/pzmyers-political-idiot.html

That’s just on bad political standards.

1. Laughably false. I’m not purging anyone, nor do I have the power to do so.

2. Harris has some views I find objectionable, including his position on Islam, his writings on torture, and some of his weird buddhist mysticism. He’s conservative on some things, not on others.

2a. Doesn’t make sense.

1. You’ve expressed your wish for a purge of conservatives, PZ, which is what I said. (Nice to know you’re not reading carefully. I never said you were actually purging anybody.)

2. Harris IS a neocon of sorts, or he certainly quacks like one and NOTjust on his Islamophobia. Beyond that, he engages in “scientism” and is generally a horribly bad writer. (Massimo Pigliucci and I had a LOT of agrement on our Amazon reviews of Immoral landscape.) He actually hits me as being kind of Orwellian.

Ergo, 2A, at least for your personal circle of “real atheists,” is a reasonable conclusion. You’ll note that I didn’t claim Hitchens was a neocon; he’s just an oft-drunken idiot, but one who willingly jumped in bed with neocons. I feel no sympathy for him being called one, even if he’s not.

And a sidebar … the same week you claimed Harris wasn’t a neocon, you also said, in effect, “I guess I’ll have to vote Democratic again.” Showing either ignorance of, or dissing of, third party options when, with the number of people who read you, you could actually make a bit of a difference, was off-putting.

Yes, the Greens are nowhere near perfect on things like alt-med. I’ll still vote Green with alt-med issues, etc., long before I vote for the left side of the corporatist duopoly.

I’m probably going to regret this, but …

1) Where does this thing about purging conservatives come from? If you are going to make a heavy claim like that, at least link to some evidence. The link to your blog post about Myers being a “political idiot” doesn’t point to any statements by Myers to that effect.

2) What does this have to do with the topic? It’s one thing to show cases of PZ exemplifying how “incivility sometimes goes hand in hand with exaggeration [and] factual inaccuracy” (though as of yet, not legal liability). That’s relevant, though a discussion of it can easily get out of hand. But PZ’s politics? Huh?

Second, let’s note your band standards on religion, PZ. As I noted on your post about Chris Steadman and “faitheism” (and, I’m not an “accommodationist,” I reject a word that Gnus made up to be a pejorative), I noted that people like you refuse to distinguish between the fundamentalist Church of Christ and the semi-unitarian United Church of Christ.

And, I’m nowhere near alone on that. Chris Hedges, though unfortunately lumping all atheists with you Gnus (see where well-poisoning leads on the PR side) wrote a whole book about that.

On “tone,” your worst problem, PZ, is that everything is black-and-white. Your world knows no shades of gray. Add in your search for cadres, and while Gnu Atheism of your stripe may not be a religion, it manifests many of the sociological aspects of a fundamentalist-type faith.

http://socraticgadfly.blogspot.com/2011/06/pzmyers-and-pharyngulacs-religious.html

Again with the cartoonish caricatures. My father was UCC. I know the difference.

I reject the adoration of faith that so many religions, from some Unitarians to the Baptists, regard as a virtue. That I reject them on the basis of a significant objectionable element that they hold in common does not imply that I see no differences between them.

Well, words are actions and speak loud enough … “religion” on your blog is almost always a shorthand for “fundamentalism,” it seems, with no distinction behind made even in cases where such a distinction could be important … as in “faitheism.” Or on civil liberties issues in general.

This has nothing to do with “adoration of faith.”

You don’t like “accommodationists,” and I guess the dislike is enough to not like being lumped with them.

It’s about accuracy …. and a sense of courtesy.

PZ Myers is going to lose his shit, I bet. That should be fun to watch.

That’s assuming he’s “had his shit.” PZ, Coyne, the Pharyngulacs and Coyneheads? For them, religion of any sort, moderation of any sort in dealing with religion, cooperative attitudes of any sort?

They all lead to Tar Baby reactions … he’s “stuck” on many of the same things he decries in fundamentalists, in the process of claiming fundies represent all believers.

It’s not just wrong, it’s intellectually lazy on the part of him and others, too.

But, speaking of dog-whistles? PZ can use the right one, and his “cadres” snap to attention.

http://socraticgadfly.blogspot.com/2011/06/pzmyers-and-pharyngulacs-religious.html

Perhaps you should practive what you preach?

“Pharyngulacs”

“Coyneheads”

“Tar Baby reactions”

“cadres snap to attention”

Not to mention your straw-man of PZ “claiming fundies represent all believers”

When you cut out all the dickish behaviour, it seems your post has precisely zero content.

This article is a keeper. Thanks, Mr. Loxton!

I wonder, though, about the account of the origins of Phil Plait’s phrase “Don’t be a dick.” The linked Wikipedia entry on Wheaton’s law says that Wheaton used the phrase with reference to playing games in a speech in 2007. But in November of 2006, two episodes of South Park were broadcast that included Richard Dawkins as a character, in the second of which a character in the future says of Dawkins: “But it wasn’t until he met his beautiful wife that he learned using logic and reason isn’t enough. You have to be a dick to everyone who doesn’t think like you” (“Go, God, Go XII“). I guess one would have to ask Phil Plait to know for sure, but I always assumed that this is where he got the idea for using the phrase.

I always assumed that Phil owed DBAD to Wil Wheaton, since they do know each other (eg: Phil’s had dinner at Wil’s house IIRC). I could swear that Phil’s had something to do with an occurrence of “Hey, Wil says, ‘Don’t be a dick!'” but that may just be the vagaries of memory right there. If Wil got it from anywhere in particular is another question.

Plait gives a citation for the phrase in the speech (at about the 24:30 mark):

He also notes the convergence that he and Rebecca Watson independently adopted this phrase to make similar points.

I am always amused at the tizzy that some people will work themselves into over the fact that no group ever is totally homogeneous. ;)

You would think we are talking with sheep herders or something….oooooooh.

Although I appreciate the effort Daniel put in the article, “toning” is probably misguided. A very important lesson of skepticism is that clarity is important because woo hides in imprecision and in the accommodation of ideas that are undeserving. Unfortunately, for many people clarity equals rudeness.

The statement: “Most likely there is no god because there is no evidence for it or any other supernatural phenomena” is infinitely rude to a lot of people but couldn’t be more clear and correct.

Similarly, the statement “No, that outfit is not flattering to you,” may be clear and correct, and it may also be quite rude. How, when, and to whom it is said make the difference.

That would be rude because it is an opinion and it would be a comment on someone’s personal tastes.

Scientific and logic statements are not (or should not be) a subjective opinion.

No, it would not be rude because it is a matter of taste. To be concerned with whether my example can offer an objective truth is to miss the point. It could be rude if it was unsolicited or if it was not offered constructively, but in the context of speaking to a friend who is concerned whether he made the right wardrobe choice it is clear, correct (let’s say that we are talking about the cut of a suit that is inappropriate for his body type – the sort of fashion choice that those with any opinion on such a matter in a society are likely to share, so that in a sense it is correct), and not rude at all. How, when and to whom it is said makes all the difference.

actually, you’re mistaken: somite’s statement that “Most likely there is no god because there is no evidence for it or any other supernatural phenomena” is a statement regardings facts (or non-facts if you prefer). On the other hand, you’re statement that “no, that outfit is not flattering to you”, while i’m sure could under given circumstances find consensus (variables including what place or time period, etc), it’s a statement about someone’s opinion on aesthetic value-and not a statement about which it is even possible to actually be “wrong”, if you take wrong to mean factually incorrect, versus the quotidian use of the word, as when someone refers to an action by saying “dude, that’s just wrong!”

Another point is that the incivility argument is a red herring. In any group of people with any label there will be people with rude personalities. However, it would be incorrect to label the group based on the actions of a few.

Chris Mooney has been making this mistake lately in his intersection blog where he attempts to demonstrate that the left can be antiscientific too by providing very narrow and specific examples, for examples aversion to nuclear energy and food woo. Some commenters have explained that woo in the left is nothing like in the right where it is part of the GOP political platform.

This is exactly like the fallacious argument that atheism leads to political atrocities because some dictators were atheists. Dawkins points out they also had mustaches but no one will blame this fashion choice for the atrocities committed.

I don’t think incivility is prominent among skeptics or atheists. Clarity is just offensive to some people and this is unavoidable if you want to promote true critical thinking.

And no. Claiming that criticism of religion is outside the purview of skepticism to avoid conflict unless undermines credibility in the long run.

my take away from this article, and to be honest, i’m really new to there being a difference between ‘skeptical’ and say, ‘atheist’, is that for those who call themselves ‘skeptics’ (i never have, though of course, as an atheist, i am), is that, perhaps from its inception among scientists and other well educated people, for our social movement, the default is the usual civility and open inquiry that can be found among most academics…which i think is laudable, but i think misses entirely the point: skepticism places one firmly outside societal norms in many different areas, including religion-and it is in the realm of the society where our battles must be fought-in and among and against a great many people who do not, as a habit, “play fair”…which ultimately, in my mind (though not in each and every instance, of course) is the equivalent to running a race against someone with a 10 yard headstart, while pulling a volkswagen beetle, and wearing shoes with a rock in each one…

In truth, given all we know about the nature of ‘mob’ mentality, methods of indoctrination and social engineering, media messaging and other aspects of the human brain, language qua language, and media/communications, i find it rather safe to say that each community (which again, i see no substantive difference in), needs the other-each of us, to steal the religious motif, carries an angel on one shoulder; a devil on the other-and both must act in concert if we’re to move forward.

one last thing:

it is possible to be something of a dick-ridicule=shame in social groups-a precursor to admitting you might be wrong about something, and therefore, a precursor to the beginnings of rational thought.

i’d say, perhaps it’s ok to be a dick, but not to take a piss in someone’s cornflakes.

Chris Mooney has also pointed out himself why the idea of a “Democrat War on Science” analogous to the Republican War on Science doesn’t wash: http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/intersection/2011/06/09/how-to-make-the-democrat-war-on-science-argument-supposing-you-want-to/ He has also pointed out in other articles that the left has expertise on its side (which unfortunately hasn’t helped much in political battles, but that’s another story).

Pointing out that people on the left have their own blind spots with regard to science isn’t engaging in false equivalence. Also, given that Mooney has already argued explicitly against false equivalence, and done so recently, reading an implication of false equivalence into his other articles is probably a mistake.

As for clarity supposedly being mistaken for incivility, I point out as an example that recently, PZ Myers (you just knew his name would come up, didn’t you) highlights approvingly a comparison between atheists working together with the religious on the one hand and leftists working with tea partiers on the other. This is not only uncivil, but it displays a lack of clear thought. Obviously, attempting to reach out and work with hardliners such as tea partiers is a fool’s game, but religious people aren’t all hardliners. For example, the Reverend Barry W. Lynn is the executive director for Americans United for Separation of Church and State, an organization that obviously benefits nontheists. By likening religious people in general to known hardliners, Myers is being the very opposite of clear, at least in this example.

On the other hand, Somite, on your last point, Gnus seemingly, at times, like to believe atheists are MORE moral than the religious.

For example, it’s debatable just what Hitler believed, even though he did come from a Catholic family.

However, in the debate over murderous atheists, Stalin’s attending an Orthodox seminary totally does NOT mean he was a Christian dictator. (By that standard, John Loftus is s still-Christian writer!)

Rather, both Stalin the atheist and Mao the atheist killed tens of millions of people.

Atheists as a group are no more immoral than religious believers, but there’s nothing intrinsically more moral about them either.

Thank you, this was a fun little review. Satire, black humor, and bombastic language have historically been condemned in nearly every other field, it’s not surprising that skepticism has its own history.

It all comes down to effective communication. Back in college, you found the nihilist atheists, the sort who quote Nietzsche out of context and sneer condescendingly at any mention of faith. Armed with a few factoids and a shoulder-chip the size of Texas, they set out to preach the glory of their own enlightenment. Given an opportunity to expound, nothing short of physical removal will get them to back off. Until they grow out of it, they are dicks. Skepticism as a movement can attract these and for a short while, coddle them.

Then you have the firebrands, who use ridicule, direct insult, flippancy, and every possible kind of dismissive language within the framework of a precise and careful rebuttal. Facts are laid out, backed up and properly referenced. They show their work. The only way to counter their argument is with faith, some version of “Well, I still believe, no matter what you say.” An answer that would not change, even if the language were more delicate.

The nihilist is very easy to dismiss, dicks always are. There is no substance, they are annoying but forgettable. The firebrand can only be dismissed by his language because his arguments are sound. Currently, skepticism as a movement is full of firebrands but has no noteworthy public “dicks.” The closest would be Penn Jillette, primarily because his chosen medium (TV show) doesn’t allow for a rigorous discussion of proof.

You can still find the dicks within the private sphere. It’s very dismaying to find yourself in agreement with the message but completely repulsed by the messenger. A quick read through any skepticism forum will unearth countless examples. The language of skepticism (Evidence? Fallacy!) is there but the purpose is lacking. Like a comedian who thinks Lenny Bruce was a genius because he cussed.

You can’t weed out these people. They are there and always will be. They will do damage within their limited sphere of influence and this will be frustrating. The best we can do is promote the firebrands who offer the finest argument regardless of language. Maybe with time, people will associate the many varieties of skeptical language with undeniable fact.

I take issue with your argument right at the ‘ “Well, I still believe, no matter what you say.” An answer that would not change, even if the language were more delicate. ‘ This is, of course, a simple generalization of those of a religious bent (or otherwise). It seems that you’re taking this generic (and, therefore, false) representation of their response as precisely the required criteria for a carte blanch approach to the matter.

First, I have to wonder: given that the “I believe no matter what” crowd is unreachable, does it really make sense to take this firebrand approach to those who don’t keep membership there? I mean, the reason why you claim it’s acceptable to act prepubescent is exactly because of this crowd who will retreat to the pure faith position… and so we ought to default to mockery when dealing with everyone because of the subset of them who are willing to shun reason? The logic here seems muddled to me.

Acting childish, even when those on the other side of the discussion do so freely, should not be condoned by anyone who truly has some reason about them.

If we exclude atheists from being counted with the rest of the skeptics just how much dickishness are we talking about here?

Well, setting aside the “dick” rhetoric (a still brand new addition to the dialogue about civility in skepticism, and not essential to it), the real question might be something more like, “Is there room for improvement in the skeptical literature and skeptical outreach?”

Writing at a time when the almost universal position of North American skeptical media and organizations was that atheism and skepticism were separate, Carl Sagan (for example) nonetheless felt that skepticism could aspire to outreach that was better grounded in science (rather than opinion); less burdened with the “tendency to belittle, to condescend”; and less tribal (“the chief deficiency I see in the skeptical movement is in its polarization: Us vs. Them”). Regarding tribalism, the very existence of skeptics who self-identify as part of a subculture could be seen as a red flag (though I’m one of them).

MCB, I don’t know what Shermer or Brian Dunning don’t or do believe on metaphysical issues.

But, because of the degree they’ve commingled skepticism and political libertarianism … they get close to my dickishness line if not transgress it.

Dickishness includes reasoning standards, etc., not just tone.

@ Daniel

“Is there room for improvement in the skeptical literature and skeptical outreach?”

No doubt. But is skeptical outreach made more difficult when the landscape has been scorched by “angry atheists?” Must all skeptics sign up for a war on religion in order to combat the Power Balance fraud, homeopathy, or the antivaxers?

“Regarding tribalism, the very existence of skeptics who self-identify as part of a subculture could be seen as a red flag (though I’m one of them).”

Please expand on this when time permits. Thanks.

I have seen a tendency for both sides of this debate to overstate the opposition. Phil opened up his speech asking if in your face obscenity shouting ever convinced anyone of anything, and taken to that extreme of course it had not.

Likewise, the other side tends to think DBAD means being a wilting lily that will quit at the first lower lip tremble of the woo purveyor.

Clearly, neither of these extremes will work. The hurt feelings of your opponent do not make you wrong any more than loud volume ad hominem attacks make you right. As a movement we should avoid both extremes if we want successful outreach.

Exaggeration on both sides has made this debate into a false dichotomy.

I’m really finding this debate rather tedious and unproductive at this point. Every movement seems to develop this dichotomy over civility vs. firebrandism. Both sides here have thoroughly laid out their positions and both sides feel their position is being straw-manned by the other. They talk past each other and no one seems to be particularly persuaded by the other side.

I see clear benefits to both sides operating simultaneously, particularly if they can play nice with each other and not go out of their way to publicly attack the other side, forcing a public response from that side. I think we all agree the key audience we’re trying to reach are the fence-sitters, and it’s quite clear that different fence-sitters respond to different approaches. Some audiences will respond to politeness while others will see it as disingenuous and be turned off. Meanwhile, some will respond to

ridicule and flippancy within the framework of a precise and careful rebuttal. Something tells me Bill O’Reilly and Glenn Beck aren’t persuasive because of their amazing ability to keep a civil, un-dismissive tone. Some audiences will just respond better to blunt, unapologetic refutations, especially if they’re built on solid arguments, while others won’t.

I think those who sit squarely on one side or the other and aren’t willing to adapt their approach based on the particular situation they’re in need to wake up and realize that there is no one magic bullet that explains all of human psychology. The available data, as little as there is, seems to show that both methods have worked in the past, so I see no reason why anyone can maintain the view that either is completely ineffective.

There’s also a wide range being ignored by this dick/not a dick false dichotomy. As someone said above: “Currently, skepticism as a movement is full of firebrands but has no noteworthy public ‘dicks.’ The closest would be Penn Jillette, primarily because his chosen medium (TV show) doesn’t allow for a rigorous discussion of proof.” The term “dick” demands clarification. It can’t reasonably be applied to just any use of confrontational or deliberately provocative approaches.

Will some people refuse to acknowledge diversity among skeptics and try to paint everyone as “angry atheists”? Probably. But they’ll do that anyway and the idea that everyone must constantly conform to one particular model in order to trick people into thinking there is no diversity among skeptics and that we’re all equally civil is absurd. Every important social movement has faced such stereotyping and they managed to survive it, so I don’t really worry about it. It’s very hard to maintain such a stereotype when there are skeptics and atheists getting news for their charitable works. Nobody has to be saddled with the Hitchens/Myers reputation if they don’t want to be. It’ll be okay.

Yes. As I mention in the endnotes, the word “dick” was never anything more than Plait’s rhetorical underlining for his (quite traditional) discussion of behaviors — behaviors that most people engage in at some times. (He specified name-calling, for example.) “Dick” isn’t and never was a category of skeptic (or, for that matter, atheist).

One of the things I hoped to illustrate with this article was that Sagan and others discussed similar issues of best practices long before this (very new) “dick” dichotomy. When Sagan, for example, described skeptics waxing “superior and contemptuous,” this was not some category of other, bad skeptics; the example he used was himself. He was critiquing an attitude, not an opposing camp.

But, like it or not … don’t we have “opposing camps” now? When “accommodationist” (more in the line of atheism than skepticism) is a deliberately pejorative word, how can there NOT be “camps”?

“I’m really finding this debate rather tedious and unproductive at this point.”

Ditto.

Can’t resist…

The Dicks, Pussies, Assholes Speech from Team America: World Police

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zcAaertdaQk

I `second’ that.

I don’t have a very positive view of Marcello Truzzi. First of all, I think the term “pseudoskeptic” is in very poor taste. It’s name-calling. It’s enforcing an ambiguous standard. It inevitably gets thrown all around until everyone is a pseudoskeptic to everyone else.

I also have the impression that Truzzi went to far in the direction of agnosticism. He very much downplays the importance of prior plausibility of claims. Downplay it too much, and you’ll get something along the lines of so-called “evidence-based medicine“. Unfortunately I am not familiar with any of Truzzi’s investigations, so I do not know how his philosophy played out in practice.

I think that ALL people who stereotype and call people NAMES are assholes!

(And think about this before you rebut my comment)

From this article I recall enjoying Phil Plait’s DBAD speech from the TAM8, but I still get caught between the rock and the hard place of presenting refuting evidence to dubious claims vs. making nice so as not to injure somebody’s sensibilities. Case in point:

My daughter attends a college with an active parent email list. A couple weeks ago one parent was lamenting that she would be unable to attend her son’s graduation because of the campus-wide wifi network and her “EMF hypersensitivity”. I did a little background reading on the topic (I was unfamiliar with the phenomenon before and certainly have no medical, psychiatric or psychological training) and it didn’t take long to learn that this is non-specific diagnosis for a panoply of physical complaints which, in some cases, may be indicative of a deeper seated anxiety and somatic disorder. Moreover, under double blind conditions there seems to be no credible evidence that people who claim EMF hypersensitivity can detect the presence of low-level, non-ionizing radiation any better than non-sufferers. I posted to the list a response stating my own skepticism, not of the phenomenon, but of the underlying causes and included links to articles to support my position. I concluded by saying that, speaking only for myself, I would not let the presence of a few routers keep me from celebrating that milestone in my child’s life.

Wow. You would have thought that I had brought a Big Pharma sales kit to a homeopathy conference! Over the next 24 hours there were dozens of vehement responses that called me everything from insensitive to egotistical to bombastic. Several people offered to send the OP info about remedies and alternative solutions to her symptoms off-list (lest they be left open to my continued criticism). I, too, received about 10 private emails of support and thanks, though only one person willing to defend my position on the public list.

When my wife, who also subscribes to the list, saw the firestorm, she said, “What about the video you showed me last summer about not being an a**hole?” (referring, of course, to DBAD) She basically didn’t speak to me for 24 hours and we’ve agreed never to talk about that incident again.

What would other skeptics have done? Let it go without comment? Tried to coddle the OP in her unhappiness over missing the event? Was I a dick? I tried to be very, very clear that I wasn’t criticizing her or her malady, only her belief in the underlying causes, and that, if it were I, given the evidence I presented, I would make a different personal choice. Where is the ethical line in a situation like this?

If I were you, I wouldn’t tell people “If I were you.”

But seriously, that’s probably what came off as egotistical.

Without seeing the correspondence, I’m not sure anybody can make an assessment on its appropriateness.

I’ve found myself in numerous situations like this, both as a teacher and as a science communicator, where I’ve needed to address cherished folk beliefs or misinformation. Nobody can tell you what the ethical line is (ethics are personal things, not physical laws), however from my perspective I always feel I have an obligation to address what I see as a myth or bad science.