Unpersuadable—and unscientific

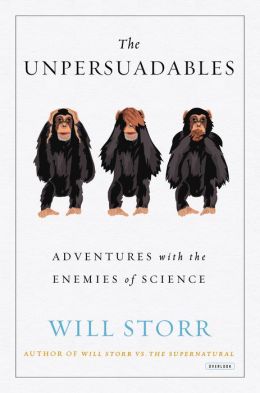

A review of The Unpersuadables: Adventures with the Enemies of Science, by Will Storr (2014, Overlook Press, New York).

Most of us long-term skeptics have had our share of run-ins with people who cling stubbornly to a particular dogma. We get frustrated that no amount of evidence or strong arguments ever changes their point of view. The pattern is true whether you’re dealing with religious beliefs (from creationism to various Eastern religious ideas), or paranormal beliefs (UFO nuts, psychics, ghosts, cryptozoology) or just plain pseudoscience and bad scholarship (homeopathy, past-life regression, Holocaust deniers, climate-change deniers, and many others). Reporter Will Storr decided to go deep into the heart of these various fringe and non-scientific belief systems, interviewing the major figures, taking part in their rituals, and doing his best to give them a fair shake as he embeds himself into their culture.

What results for these many years of immersion in the strange and weird world of belief systems is quite a portrait of what he calls “the enemies of science.” Storr manages to cover almost the full range of “weird beliefs”: creationism, UFO nuts, Yogi Ramdev and his followers, psychics, past-life regression, Vipassana Buddhist meditation, homeopathy, the strange psychosomatic “disease” known a Morgellons syndrome, the “Hearing Voices Network” of people who reject their diagnosis of schizophrenia, false memory syndrome, the climate change deniers, Holocaust deniers, Rupert Sheldrake and his paranormal fantasies, and many others. In most cases, he does not directly condemn them, or preach about the weird stuff he hears from these people. Instead, he describes the events in a non-judgmental way, and lets the people speak for themselves—and hang themselves with their own words, especially as his questions lead them to say weirder and weirder things. This is especially apparent as he spends many days with Holocaust denier David Irving and his pack of neo-Nazis, watching them delude themselves as they spout one racist statement after another—and then they claim they’re not prejudiced or anti-Semitic. Surprisingly, he finds that Holocaust denial is not their main purpose—they just worship Hitler and the Third Reich, and so must discredit anything that besmirches the reputation of Der Führer.

Just spending a few days with notorious climate denier Lord Monckton, and you quickly see what motivates him: he’s an old-school aristocrat, a colonialist, elitist and racist who hates any attempts to regulate business or restrict the privileges of his rich upper-class peers. Storr lets Australian creationist John Mackay go on and on until he hangs himself with the contradictions inherent in literal interpretation of the Bible, and begins to spout bizarre ideas that are Bible-based. Storr tracks down the facts behind the death of a young woman who had been convinced by “psychologists” that her family had molested her, planting her full of “false memories”, so she ended up committing suicide. (This case sounds very similar to those in the U.S., such as the famous McMartin preschool case, where innocent school officials were accused of molestation and satanism and many other false things by rogue psychologists planting false memories in the minds of the children). He develops some sympathies for Harvard Professor John Mack, who was drummed out for advocating the reality of UFO abductions—even though Storr doesn’t believe that Mack was right. His descriptions of the physical self-torture followed by the Yogi Ramdev cult, or the extreme monk-like ascetic practices of the Vipassana Buddhists, are particularly gripping—and hilarious, as his westernized thinking and bodily needs clash with the eastern physical self-abuse and self-denial that these people practice.

Through each of these stories, he weaves the findings of psychologists and neuroscientists about how the human mind works, and how our brain can believe all these weird things. As many other people have shown, despite our best efforts our brains are not “objective” or “rational” in any way. Instead, we form a “belief network” around ourselves, and use confirmation bias to resolve the inherit conflict caused by the cognitive dissonance of what we want to be true, and what the world shows us. We easily fall for anecdotal thinking. Our bodies respond to placebos just as readily as they do to almost any treatment (including some Western medicine). As Michael Shermer says, we are “belief engines”. Our minds form a picture about our world early in our development, and almost nothing will change this as we grow and learn more about the world. Instead, we filter what we see and hear so only the stuff that makes us happy and convinced that we’re right gets through. At the end, there isn’t really an “objective” world for any human being, since we are all products of a world of information filtered by biases (both conscious and unconscious). Finally, Storr despairs that any of us can find a “reality” that has some meaning beyond the person who entertains it. We all want our “stories” to be true, and ourselves to be the flawless “heroes” of our own story—and facts seldom prevent this, no matter how deluded we are.

Even though Storr subtitled the book “Adventures with the Enemies of Science,” and constantly checks what his subjects claim against scientific research, he’s not too pleased with the skeptical movement either. He reports on the famous “homeopathic overdose” event in Britain, and finds that most of the crowd is just copying what their peers are doing—few have done much reading, or know much of the evidence of why homeopathy is fake. He attends The Amazing Meeting in Las Vegas, but finds many of the skeptics there are too smug and sure of themselves, even though they have never personally investigated why the claims they reject are wrong. He even delves deeply into the life of James Randi and his critics, and argues that there some troubling allegations that are never completely resolved. As he puts it (p. 310):

Anyone who proudly declares himself a freethinker betrays an ignorance of the motors of belief. We do not get to choose our most passionately held beliefs, as if we are selecting melons in the supermarket. . . This monoculture we would have, if the hard rationalists had their way, would be a deathly thing. So bring on the psychics, bring on the alien abductees, bring on the two John Lennons—bring on a hundred of them. Christians or no, there will be tribalism. Televangelists or no, there will be scoundrels. It is not religion or fake mystics that create these problems, it is being human. Where there is illegality or racial hatred, call the police….Where there is misinformation, bring learning. But where there is just ordinary madness, we should celebrate. Eccentricity is our gift to one another. It is the riches of our species. To be mistaken is not a sin. Wrongness is a human right.

Here, I’m not so sure Storr has captured the full story. He clearly states that he is in favor of the reality that is presented by the scientific community, but toward the end of the book he seems to devolve into a narcissistic solipsism, or to the post-modernistic view that there is no objective reality. Storr seems to be saying that since no individual has a clear view of the world, therefore there is no reality out there, and any truth or view is as good as the next. Unfortunately, he misses a key point here. Yes, individual scientists are not perfect, and have a viewpoint limited by their backgrounds and assumptions. Yes, small communities of scientists could be wrong. But Storr never discusses the real reason that he (and most people in the world) accept that there is a scientific reality outside of us: because it works. Science is the only method we know to get past individual blind spots, and subject our cherished ideas to the harsh gantlet of peer-review. Scientific ideas are unlike anything that an individual believes, because they are scrutinized and tested and criticized by the rest of the scientific community. Scientific ideas lead to predictions about the real world that can be tested, which would not be true if the scientific world were only a construct of our brains (as some allege). Only if ideas survive this intense testing phase do they eventually become part of our canon of “scientific reality”—and thanks to that scientific reality, we can launch spacecraft into the unknown and predict what they will do; we can conquer most diseases and physical ailments; we can have technology and inventions that were not possible before the scientific revolution, and our world is vastly different since then. None of the “alternative medicines” can make this claim, nor is there any rival to science for producing a world that is immeasurably better for all of us.

Still, I would agree with Storr that nobody is a saint. Nobody is perfect. Nobody is free of bias. As Storr concludes (p. 314):

We are all creatures of illusion. We are made out of stories. From the heretics to the Skeptics, we are all lost in our own secret worlds. We are just ordinary heroes fighting phantom Goliaths, doing our best in the service of truth when the only thing we really know are the pulses [of electricity in our brains].

Does Storr also look into the crackpot belief systems of those who believe there is a “patriarchy” dedicated to oppressing women, or a racist conspiracy dedicated to oppressing black people in America? Or those who believe there is a “denialist” conspiracy about climate change?

Just askin’, mind.

Trimegistus: as I understand it, “patriarchy” in a feminist context simply means a society that functions in such a way that the most advantaged people tend to be men rather than women. It does not imply that this state of affairs is maintained by some shadowy group of men dedicated to anything.

Of course, there are men out there intentionally trying to control women, but that has nothing to do with the meaning of the term “patriarchy”.

Will Storr said:

Where there is… racial hatred, call the police

How authoritarian. Though I guess this is to be expected from a modern British leftist.

Trimegistus, I’ve read scientific studies regarding the entrenched and ongoing discrimination against women and blacks supporting those hypotheses you ridicule. (Sorry, no references, I’m just recounting what I remember.) I wouldn’t call the climate change denialist effort a conspiracy so much as an agreement by rich, unscrupulous people that climate change mitigation will hurt their bottom lines, and therefore must be prevented.

Regarding Don’s review, I’m glad to hear of a book that presents the fringe without denigrating people personally. The ideas are bunk, but they’re sincerely held for the most part, and the holders are ordinary human beings like the rest of us. These are lessons all of us need to remember; those of us who like to think we have a scientific outlook do ourselves and others no service by leaving our humility behind.

I think this book needs to be added to my already laughably long reading list.

IOW, only Will Storr has a handle on reality.

Thanks for warning me away from this book.

No, he makes it clear that he doesn’t think his viewpoint is any more privileged than any other. I thought I said that in the review.

But that is part of the particular bias of MikeB . Because Storr is a leftist, he is authoritarian.

From the excerpt you posted it seems Storr, rather than attacking skeptics for their naive trust of science, is actually going against the belief that some skeptics seem to hold. Namely that if everybody were skeptics the world would be a better place. Storr seems to believe this is nothing more than tribalism. I agree.

As an active skeptic myself I’ve encountered this belief many a time and have railed against it for being exactly that. Tribal, elitist and without rational merit. I strive for a world where the tools of scientific skepticism are commonplace because I believe that would make a lot of discussions far more productive and would prevent some ridiculous tragedies. However it seems rather obvious to me that being skeptical, rational or atheistic do not equal goodness in any sort of meaningful way.

Then again, you actually read the book so you probably understand better than I what Storr actually meant.

Thanks for the post

And a good day to you Sir.

Your review, in my opinion, is a bit TOO extensive. I think you’ve put so much in your review that many people will be satisfied with your overview and not get the book. That’s good for them, I guess, but not great for the author. So I’m going to buy the book to support Storr’s efforts and in the hopes he does more in this arena. I hope others do, too.

Cheers.

I guess that’s a compliment. I prefer longer reviews that give me a good idea what the book says, so I can decide if I want to spend my precious time on reading it myself. Short reviewers are like teasers and often disappoint….