Leakey’s Luck—or Leakey’s Laughingstock?

Last Saturday, January 14, our Skeptic Society field trip “Viva Mojave” passed by a freeway exit marked “Calico Early Man Site”. On the bus, I briefly discussed the story behind the sign, but it an interesting object lesson about science and skepticism that bears repeating here.

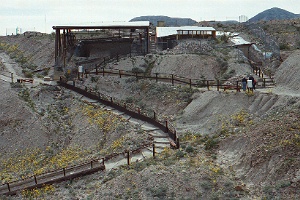

If you drive up the bumpy road, you will find a few sheds, trails with railings, and pits in the ground, and on weekends, maybe a volunteer or two. There is a dedicated support group with its own website, and the BLM maintains the site as if were a legitimate scientific discovery. Even the Wikipedia entry seems to be written by a true believer, with only minimal mention of what the professional archeological community thinks about the site. But in the anthropological profession, the “Calico Early Man” site is a running joke which became a blemish on the career of the famous anthropologist Louis Leakey—yet the loyal amateur acolytes still promote it.

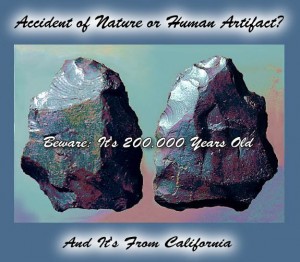

The Calico “site” was first discovered by amateur archeologist Ruth DeEtte “Dee” Simpson. It is located on the eastern side of the Calico Mountains northeast of Barstow, California, high on the steep slopes of gravel that come off the mountains during floods. The Calico site is on the edge of Ice Age Lake Manix, which flooded the Mojave Desert in this region for the last 500,000 years, and produces a wide variety of late Ice Age mammal, bird, reptile, fish, and invertebrate fossils. The “artifacts” are largely of cobbles and pebbles; no other commonly found artifacts, such as animal bones, human bones, wood fragments, charcoal, or non-tool artifacts, occur there. The “tools” themselves are very crude, consisting mostly of cobbles that have one or two surfaces flaked away to make a crude “choppers” or “hand axes”, supposedly like the crude tools of the Oldowan culture of Africa found from deposits formed about 2 million years ago. As the “Friends of the Calico Site” webpage confesses:

It is easy to scoff at the Calico “tools” the first time one sees them. They are far from the familiar beautifully-crafted arrowheads and spear points we find in surface and near-surface Indian/PaleoIndian sites across North America.

And that’s exactly what most professional archeologists thought when they saw the specimens. They have mostly been skeptical of their human origins because there are so many other ways to cause rocks to flake and fracture, especially in the high-energy setting of cobbles bashing against each other in an alluvial fan during flooding. Archeologists have been fooled and embarrassed many times in the past over-interpreting naturally broken and flaked stones, so now the criteria for an artifact are very strict. In the case of the Calico site, several analyses have been conducted (Haynes, 1973; Duvall and Venner, 1979; Payen, 1982), and they have all demonstrated that there is no conclusive evidence for human production for most of the “artifacts.”

In addition to the “artifacts,” amateur enthusiasts have pointed to “fire rings” in the gravel as proof that humans were once there. Of course, in any surface with a random covering of large cobbles, there will be by chance some that form a “ring” if they are sparsely scattered. It’s a classic case of pareidolia—seeing patterns in clouds or tea leaves or stones that aren’t real, since humans minds are programmed to “see” patterns even when they aren’t there. The crucial test of this “fire ring” model occurred in 1985-1986, when Caltech undergraduate Janet Boley, working in my friend Joe Kirschvink’s lab at Caltech, did a decisive experiment. Out at Calico, they built a “control” bonfire which burned for seven hours. Then Janet drilled paleomagnetic sample cores of both the inner side of the control ring cobbles (which were heated enough to remagnetize the rocks in a new direction) and the outer side. The outer side of the fire ring cobbles were not heated as much, so the rocks retained their random magnetic directions. Then she took drill cores of the oriented “prehistoric fire ring” stones and measured them. Their magnetic directions were all randomly distributed, with no evidence they had ever been heated enough to remagnetize or have been part of a fire pit. Although she was cautious in her conclusions, it could not have been a more convincing test of the “fire ring” model—and it failed the test.

Thus, there are whole list of reasons to doubt the Calico “early man site”. First, there is no conclusive evidence that the “artifacts” are made by humans, and the “fire rings” are also natural consequences of pareidolia of randomly scattered rocks, not artifactual. Second, it is suspicious because there are only large broken cobbles that could be produced naturally, without a single human or animal bone fragment (nearly always found in legitimate archeological sites), piece of wood or charcoal, or non-tool artifact. In addition, the story is even more improbable since there are about 60,000 “choppers” or “hand axes”, far more than any normal archeological site (no matter how long it was occupied).

But the reason the site is so controversial is the age of the “artifacts”: according to thermoluminescence and uranium-thorium dating, some of the “artifacts” are 135,000 to 200,000 years old (Bischoff et al., 1981; Debenham, 1998). If true, this would radically change all of North American archeology. These dates contradict the huge number of sites which show that humans reached North America sometime after 15,000 years ago (possibly as early as 30,000 years ago, if a few controversial sites are to be believed). This makes the site at least 20 times as old as any New World site, and suggests that peoples with an Oldowan culture found around 2 million years ago in Africa were still lingering in Asia 200,000 years ago (where we have good evidence that the humans had a much more advanced culture), then migrated to North America—without leaving any evidence from any other site in any other part of the New World. As Carl Sagan put it, “extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence,” yet the evidence for this claim which flies in the face of nearly everything we know about human prehistory is extremely shaky and easily attributed to non-human causes. [This does not apply to the Rock Wren biface, a real artifact found in a younger deposit dated by thermoluminescence at 14,400 +/- 2,200 years ago, within the range of the conventional dates of appearance of humans in the New World].

The saddest part of the story was the involvement of the legendary anthropologist Louis S.B. Leakey. He was one of the most famous scientists in the world at that time, with the earth-shaking discoveries of million-year-old hominids in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, in the 1950s. During the last part of his life, he was a scientific celebrity, with a gigantic following. Huge crowds attended his dynamic lectures, and the National Geographic Society funded his research which ended up in the pages of their magazine. But according to Morell (1995, p.. 366-368) and many other sources, Louis was a better publicist and fund-raiser than he was a scientist. His second wife Mary Nicol Leakey actually found the famous “Nutcracker Man” (named by Louis as Zinjanthropus boisei) that made Louis’ reputation. She also did the careful work on the archeology of Olduvai that proved that very ancient humans made Olduwan tools.

In 1959, Louis Leakey was at the British Museum in London when Dee Simpson brought him some Calico “artifacts.” Familiar with the genuine tools from Olduvai, Louis was convinced (although Mary, who knew the tools better, was not). Louis was motivated not only by the urge to find another spectacular discovery that would enhance his reputation, but also by his pet theory that Native American languages were too divergent to have formed only in 11,000 to 15,000 years after humans immigrated here from Asia. By 1963, he had funds from the National Geographic Society for Calico, and the excavations began in earnest.

Nevertheless, most other professional archeologists found the evidence unconvincing, especially given the enormous burden of proof that this unconventional hypothesis had to meet. By the late 1960s, Louis and Mary had separated because (according to Morell) she thought he had gone off the deep end with the Calico site, but also because she was now receiving recognition as the real scientist of the group (and she was tired of Louis’ constant philandering). Nevertheless, Louis organized a conference of archeologists to come visit the site in 1970, including such luminaries of African anthropology as Desmond Clark and Glynn Isaac. But Leakey was profoundly disappointed when they came away unconvinced (even though they wanted to believe such a prominent member of their profession, and wanted to give him the benefit of the doubt). Louis died in 1972, heartbroken over his failure at Calico and suffering from a number of ailments. Leakey’s story is much like some of the other famous scientists who became known for embarrassing mistakes late in life (discussed in my “Linus Pauling effect” column of last spring).

Nevertheless, the Calico site continues to have a loyal amateur following who refuse to listen to professional archeologists or consider the problems with the site or the evidence against it. I’ve found they have an almost cult-like dedication to this lost cause, just like the amateur cryptozoologists who persist in tramping through the woods to find Bigfoot, no matter how poor the evidence is. And as long as the BLM and some local museums continue to refer to it as an archeological site, and the loyal followers keep working there, no amount of evidence or arguments by professional archeologists with much more training and experience will ever dissuade them. And, of course, it doesn’t help the situation that the BLM and other government bodies treat it as a legitimate site and not a monumental waste of time and money.

And so, as you drive I-15 between Barstow and Vegas some day, note the “Calico Early Man Site” road sign—and remember, even highway signs can be wrong…

References

- Bischoff, J.L., R.J. Shlemon, T.L. Ku, R.D. Simpson, R.J. Rosenbauer, & F.E. Budinger, Jr., 1981. Uranium-series and Soils-geomorphic Dating of the Calico Archaeological Site, California, Geology Vol. 9 (12), pp. 576–582.

- Debenham, N., (1998) Thermoluminescence Dating of Sediment from the Calico Site (California) (CAL1), Quaternary TL Surveys, Nottingham, United Kingdom, 1998.

- Duvall, James G., and Venner, William Thomas, “A Statistical Analysis of the Lithics from the Calico Site (SBCM 1500A), California”, Journal of Field Archaeology, Winter 1979: Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 455–462.

- Haynes, Vance (1973) The Calico Site: Artifacts or Geofacts?, Science, vol. 181, no. 4097, July 27, 1973, pp. 305–310.

- Morell, Virginia (1995) Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Humankind’s Beginnings, Simon & Schuster, New York, pp. 366–368.

- Payen, L., 1982. Artifacts or geofacts at Calico: Application of the Barnes test, in Ericson J., Taylor, R., and Berger, R., eds., Peopling of the New World. Los Altos, California: Ballena Press, pp. 193–201.

I completely agree with your post and your assessment of the Calico Hills site. However, your statement that “human or animal bone fragment”[s] are “nearly always found in legitimate archeological sites” raised some eyebrows with me (I am a professional archaeologist).

A very large number, perhaps even the majority, of (Palaeolithic) archaeological sites actually do not have any organics preserved. It is just that those who have, get more attention.

– Dr Marco Langbroek (palaeolithic archaeologist at the VU University Amsterdam)

As someone with a degree and some field experience in Anthropology (emphasis in Archaeology), I appreciate you bringing this bit of professional embarrassment to light. I’m glad you included the history of the Leaky’s and their separate and unequal contributions to the field as this is not widely known.

Why the BLM persists in lending their initials to this, I cannot imagine. Why would the views of these “amateurs” be taken seriously by any government agency to begin with? Amateurs are just wannabes who didn’t get the degrees–kinda just like all the other quacks!

I would hope, but not expect, that teaching students how to recognize when they are wrong is now part of a good science education? [And how to deal with it professionally.]

In the case of teaching students how to recognize questionable artifacts, I assume that this is taught somewhere in archeology classes, and I know that the Calico example is brought up as one of these cases gone wrong. But I’ve never taught anthro, so I can’t tell you for sure…

I’ve passed by the Calico sign a few times but always assumed it referred to a legitimate Native American site. Thanks for the info.

I have seen that sign a dozen times and never stopped to wonder what was behind it. Maybe I was too focused on the highway or just didn’t have brain in gear.

Thank you for writing up the story.

No kidding. Like others, I’ve driven by the sign a million times and always wondered what it referred to. Now I might want to go there more than ever!! :-)

Sounds like another Skeptics in the Jeep trip.

Another case when an extraordinary claim does not present the necessary extraordinary evidence. Thanks Dr. Prothero.

Such a cool story. This is the kind of story they *should* be relating in a critical / scientific thinking class for HS students and undergraduates. Lots of lessons here:

1. Even the smart guys get it wrong sometimes.

2. Sometimes the real smart guy is the smart guy’s wife.

3. Evidence matters.

4. Even in an historical science like archaeology, hypotheses can be tested.

5. Giving something a name does not automatically imbue the thing with all the properties normally associated with the name (“Calico Early Man Site,” “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” “Scientific Creationism,” “No Spin Zone,” “Fair and Balanced.”)

6. Not every self-described expert is a scientist.

Just think if the legitimate interest of the true believers could be channeled to something productive.

It’s nice that some folks have found a personally compelling reason to get outdoors, get some exercise and meet friends.

So if the Rock Wren biface is considered to be legitimate then isn’t this a legitimate Early Man site? It’s just not as old as Leakey was hoping.