by

Michael Shermer, Feb 12 2013

In this year’s annual Edge.org question “What should we be worried about?” I answered that we should be worried about “ The Is-Ought Fallacy of Science and Morality.” I wrote: “We should be worried that scientists have given up the search for determining right and wrong and which values lead to human flourishing”. Evolutionary biologist and philosopher of science Massimo Pigliucci penned a thoughtful response, which I appreciate given his dual training in science and philosophy, including and especially evolutionary theory, a perspective that I share. But he felt that my scientific approach added nothing new to the philosophy of morality, so let me see if I can restate my argument for a scientific foundation of moral principles with new definitions and examples.

First, morality is derived from the Latin moralitas, or “manner, character, and proper behavior.” Morality has to do with how you act toward others. So I begin with a Principle of Moral Good:

Always act with someone else’s moral good in mind, and never act in a way that it leads to someone else’s moral loss (through force or fraud).

You can, of course, act in a way that has no effect on anyone else, and in this case morality isn’t involved. But given the choice between acting in a way that increases someone else’s moral good or not, it is more moral to do so than not. I added the parenthetical note “through force or fraud” to clarify intent instead of, say, neglect or acting out of ignorance. Morality involves conscious choice, and the choice to act in a manner that increases someone else’s moral good, then, is a moral act, and its opposite is an immoral act. Continue reading…

comments (78)

by

Michael Shermer, Jan 15 2013

The following article was first published on Edge.org on January 13, 2012 in response to this year’s Annual Question: “What Should We Be Worried About?” Read Michael Shermer’s response below, and read all responses at edge.org.

The Is-Ought Fallacy of Science and Morality

Ever since the philosophers David Hume and G. E. Moore identified the “Is-Ought problem” between descriptive statements (the way something “is”) and prescriptive statements (the way something “ought to be”), most scientists have conceded the high ground of determining human values, morals, and ethics to philosophers, agreeing that science can only describe the way things are but never tell us how they ought to be. This is a mistake.

We should be worried that scientists have given up the search for determining right and wrong and which values lead to human flourishing just as the research tools for doing so are coming online through such fields as evolutionary ethics, experimental ethics, neuroethics, and related fields. The Is-Ought problem (sometimes rendered as the “naturalistic fallacy”) is itself a fallacy. Morals and values must be based on the way things are in order to establish the best conditions for human flourishing. Before we abandon the ship just as it leaves port, let’s give science a chance to steer a course toward a destination where scientists at least have a voice in the conversation on how best we should live.

We begin with the individual organism as the primary unit of biology and society because the organism is the principal target of natural selection and social evolution. Thus, the survival and flourishing of the individual organism—people in this context—is the basis of establishing values and morals, and so determining the conditions by which humans best flourish ought to be the goal of a science of morality. The constitutions of human societies ought to be built on the constitution of human nature, and science is the best tool we have for understanding our nature. For example Continue reading…

comments (52)

by

Steven Novella, Jan 07 2013

What is the proper basis for morality? This question comes up frequently in skeptical circles for various reasons – it tests the limits of science, the role of philosophy, and is often used as a justification for religion. There has been a vibrant discussion of the issue, in fact, on my recent posts from last week. The comments seemed to contain more questions than anything else, however.

Religion and Morality

Often defenders of religion in general or of a particular set of religious beliefs will argue that religion is a source of morality. They may even argue that it is the only true source of morality, which then becomes defined as behavioral rules set down by God.

There are fatal problems with this position, however. The first is that there is no general agreement on whether or not there is a god or gods, and if there is what is the proper tradition of said god. There are scores of religions in the world, each with their own traditions. Of course, if god does not exist, any moral system based upon the commandments of god do not have a legitimate basis (at least not as absolute morality derived from an omniscient god).

Continue reading…

comments (110)

by

Michael Shermer, Sep 11 2012

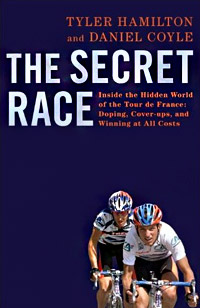

The Hidden Price of Immoral Acts

I’ve been reading Tyler Hamilton’s new book, The Secret Race: Inside the Hidden World of the Tour de France: Doping, Cover-ups, and Winning at All Costs, co-authored by Daniel Coyle, a journalist and author with considerable literary talent. It’s a gripping story about how Tyler Hamilton, Lance Armstrong, and all the other top cyclists have been doping for decades, using such advanced scientific programs of performance enhancement that estimates show the benefit could be as much as 10%, in races won by fractions of 1%. After nearly two decades of racing with both dope and no dope, Hamilton concludes that although a clean rider might be able to win a one-day race, it is not possible to compete in, much less win, a 3-week event like the Tour de France.

The lengths these guys go to win are almost beyond comprehension. All you do is train, eat, and sleep. And dope. The drug of choice is (or was—now that the drug testers have caught up riders use other drugs that have similar effects) EPO, or erythropoietin, a genetically modified hormone invented by Amgen that stimulates the body to produce more red blood cells, a life-saver for anemic patients undergoing chemo or suffering from other long-term ailments. Also on the menu is testosterone, human growth hormone, steroids (for injuries, not bulk, since cyclists get as skinny as they can), and others. Tyler nicknamed his EPO Edgar, as in Allen Poe. The drugs worked, he says, but only if Continue reading…

comments (47)

by

Michael Shermer, Nov 09 2010

As a skeptic and atheist I am often asked, “What do you believe in?” The ending preposition implies something more than what factual claims are to be believed, such as evolution, quantum physics, or the big bang. What is suggested by the question is what values does one believe in or hold to, especially without belief in God and religion. Here is my answer.

I believe in the Principle of Freedom: All people are free to think, believe, and act as they choose, so long as they do not infringe on the equal freedom of others.

I believe in civil liberties, civil rights, and the freedoms guaranteed in the United States Constitution, including and especially freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom to assemble peacefully, freedom to petition grievances, freedom to worship (or not), freedom of the press, freedom of reproductive choice, freedom to bear arms, etc. Continue reading…

comments (139)

by

Michael Shermer, Sep 07 2010

A reply to Jerry Coyne

In his endearingly titled blog, “Michael, we hardly knew ye,” the venerable evolutionary biologist and slayer of creationist dragons Jerry Coyne (author of Why Evolution is True) wonders if I’ve gone ‘round the bend over capitalism and sold my skeptical soul to the Templeton Foundation, the alleged evil subsidizers of religious and capitalist propaganda. Allow me to set the record straight (again) for all my critics out there (and in reading the comments to Jerry’s blog there’s more than I thought, and many of them are darned right caustic!). Continue reading…

comments (71)

by

Daniel Loxton, Aug 27 2010

Skeptics and parallel rationalist communities spend a lot of time on “inside baseball” — jargon-filled debates about technical matters that seem incomprehensible, dull, or ridiculous to outsiders. These shouldn’t be the main skeptical topics (shouldn’t we be busy solving mysteries and educating the public?) but some discussion on these matters is unavoidable and worthwhile. Many movement-oriented skeptics and organizations have things they hope to accomplish; with goals, there comes discussion of best practices.

Skeptics and parallel rationalist communities spend a lot of time on “inside baseball” — jargon-filled debates about technical matters that seem incomprehensible, dull, or ridiculous to outsiders. These shouldn’t be the main skeptical topics (shouldn’t we be busy solving mysteries and educating the public?) but some discussion on these matters is unavoidable and worthwhile. Many movement-oriented skeptics and organizations have things they hope to accomplish; with goals, there comes discussion of best practices.

Among these insider debates, none is more persistent than that of “tone.” Hardly a week goes by that some tone-related tempest doesn’t spill out of its teacup and across the blogosphere. And yet, these issues matter to many (including me). When people devote enormous energy to skepticism, dedicate careers to skeptical outreach, or generously commit volunteer hours or donations to skeptical projects and organizations, it’s natural that abstract internal debates about the soul of skepticism are perceived to have powerful importance.

Continue reading…

comments (243)

by

Michael Shermer, Jan 12 2010

Nothing fuels religious extremism more than the belief that one has found the absolute moral truth. Islamic terrorism, for example, has gradually shifted from secular motives in the 1960s to religious motives today. A 2000 study by the state department that resulted in the publication Patterns of Global Terrorism, found that in 1980 there were only two out of sixty-four militant Islamic groups whose mission was religiously based. In 1995 that figure had climbed to nearly half. The figure is undoubtedly higher today. (http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/54249.pdf)

It is a type of fuel that can lead to what Clay Farris Naff, Executive Director of the Center for the Advancement of Rational Solutions in Lincoln, Nebraska, cleverly calls the “neuron bomb,” after its cold-war counterpart, the “neutron bomb,” designed to kill people while leaving buildings and infrastructure in tack. A schematic of the neuron bomb looks like this: Continue reading…

comments (52)

by

Michael Shermer, Aug 18 2009

Did humans evolve to be religious and believe in God? In the most general sense, yes we did. Here’s what happened.

Long long ago, in an environment far far away from the modern world, humans evolved to find meaningful causal patterns in nature to make sense of the world, and infuse many of those patterns with intentional agency, some of which became animistic spirits and powerful gods. And as a social primate species we also evolved social organizations designed to promote group cohesiveness and enforce moral rules.

People believe in God because we are pattern-seeking primates. We connect A to B to C, and often A really is connected to B, and B really is connected to C. This is called association learning. But we do not have a false-pattern-detection device in our brains to help us discriminate between true and false patterns, and so we make errors in our thinking Continue reading…

comments (138)

Skeptics and parallel rationalist communities spend a lot of time on “inside baseball” — jargon-filled debates about technical matters that seem incomprehensible, dull, or ridiculous to outsiders. These shouldn’t be the main skeptical topics (shouldn’t we be busy solving mysteries and educating the public?) but some discussion on these matters is unavoidable and worthwhile. Many movement-oriented skeptics and organizations have things they hope to accomplish; with goals, there comes discussion of best practices.

Skeptics and parallel rationalist communities spend a lot of time on “inside baseball” — jargon-filled debates about technical matters that seem incomprehensible, dull, or ridiculous to outsiders. These shouldn’t be the main skeptical topics (shouldn’t we be busy solving mysteries and educating the public?) but some discussion on these matters is unavoidable and worthwhile. Many movement-oriented skeptics and organizations have things they hope to accomplish; with goals, there comes discussion of best practices.