by

Donald Prothero, Nov 02 2011

Even before the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America (GSA) in Minneapolis started on October 9, there was a huge buzz among my colleagues about this remarkable abstract that claimed evidence of a giant squid, or “Kraken”, that had arranged the bones of the whale-sized ichthyosaurs (marine reptiles shaped like dolphins) from Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada. There was a post on the October 10 page of Pharyngula.org, and also one on Brian Switek’s Laelaps blog, “The Giant Prehistoric Squid that Ate Common Sense”. The only things geologists and paleontologists could evaluate was a short abstract, but it made such a sensational claim that the press was buzzing and the story was all over the internet.

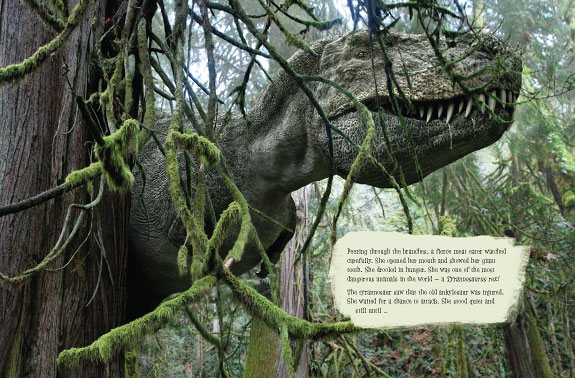

Image of the ichthyosaur bones, showing the "alignment" of the disk-shaped vertebral centra that are alleged evidence of cephalopods arranging the bones.

Based on the abstract and the GSA press release, the argument seemed to be absurd. The only positive evidence presented before the talk occurred was the claim that the bones were arranged in a pattern that resembled the alternating pattern of suckers on the arm of a giant squid. No actual physical evidence of the squid itself—no soft parts, no tentacle hooks, not even the hard “pen” that holds up the back of the animal, or its horny beak. The only “evidence” given in the press release was the alternating pattern of the vertebral centra (the large disk-shaped bones in the photograph). According to the author, this was evidence of a conscious effort on the part of a large cephalopod to “arrange” them that way! There was no mention of the possibility that any string of disks connected in the vertebral column would settle in that pattern once the tissues rotted and fell away from the backbone. No suggestion that the entire premise of the talk was just speculation based on a “pattern” of bone distribution, or “seeing patterns” where there are none, known as pareidolia (such as seeing the Virgin Mary in a grilled cheese sandwich, or reading “patterns” in tea leaves and clouds). PZ Myers of Pharyngula.org immediately got very suspicious, as did Brian Switek, and so everyone was itching to find out if there was more to this story than just a press release. Continue reading…

comments (9)

by

Daniel Loxton, Oct 11 2011

by

Donald Prothero, Sep 21 2011

Two weekends ago, the country was absorbed in remembering the events of September 11, 2001, but September 10 was another anniversary: the 70th birthday of Stephen Jay Gould, paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, historian of science, Harvard professor, prolific writer and columnist, and probably one of the most influential public scientists of the 20th century. A number of prominent evolutionary biologists and bloggers paid tribute to him, including P.Z. Myers, Jerry Coyne, and others. Even though Steve lived to the age of 60 and passed away on May 20, 2002, most of us were shocked when he was stricken so suddenly by cancer and wasted away to nothing in a matter of weeks. In spite of his rapid decline in health, during his final semester he gamely kept traveling up from his New York apartment to Harvard to teach his classes, even though he was so weak he could barely stand. Though he accomplished more in his lifetime than any other scientist of his generation (books, essays, research, scientific papers, etc.), most of us felt that his death at 60 was premature and that he had so much more to offer us had he lived his fullness of years.

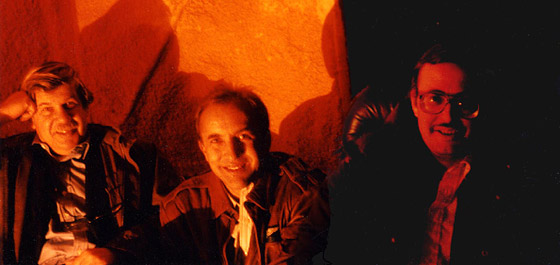

Yours truly (right) with Gould (left) and Michael Shermer (center) at Mount Wilson Observatory, 2001.

I should explain to the reader of my personal perspective in this matter. Although I was never formally his student, Stephen Jay Gould was a friend and mentor to me while I was at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) as a graduate student from 1976-1982. When I arrived at the Columbia/AMNH program, all the grad students heard the legends of Steve when he was a grad student in the same program two generations earlier. Each year, the stories got more and more amazing: how he outshone all the other students with his brilliance, published his first paper early in grad school, wrote entire papers in a few hours of work, wrote his entire dissertation in a few hours/days/weeks when his advisor Dr. Norman Newell thought he should finish and defend, and so on. His were enormous shoes to fill, and we all felt his shadow when we were being evaluated as students. I saw him on numerous occasions when I was a grad student, not only at professional meetings, but also when he came down to Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory to see for himself the work that Dave Lazarus and I (Lazarus et al. 1982) were doing on gradual evolution in plankton (he was more open-minded that you would expect), or when fellow student Paul Sereno and I paid a visit to him at Harvard while we were working on a project on allometry and dwarfing in mammals (Prothero and Sereno 1982). Subsequently, he was extremely supportive to me during my professional career, recommending me for a Guggenheim Fellowship (which I got, thanks to him), plugging my work in his Natural History columns several times, and graciously replying to my letters whenever I had an idea that truly required his attention. When my job and my department at Knox College were about to be eliminated in 1983-1984, he spoke out not only in front of the audience at the GSA meeting, but also wrote letters on our behalf to try to reverse the decision. Thus, I cannot claim to be impartial about Steve, but I do speak from personal experience and from watching paleontology change over the past 40 years.

Continue reading…

comments (17)

by

Donald Prothero, Aug 17 2011

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

—William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

ITEM: A few years ago there was a big fuss in the media about the fact that astronomers had demoted Pluto from one of the classic nine planets to a “minor planet,” just another body in the solar system. Some people were shocked and upset, since they had always learned that Pluto was the ninth planet and didn’t want to unlearn it, no matter what astronomers said. Astronomers pointed out that numerous other small icy objects had been found in the Kuiper belt outside Neptune, including some that were larger than Pluto—but no one was ready to promote 2060 Chiron to the 10th planet. Instead, the logical solution was to demote Pluto to the class of “dwarf planets” along with these other objects, since it really didn’t have much in common with the other eight planets. The state legislatures of Illinois (where Pluto discoverer Clyde Tombaugh was born), New Mexico, and California passed resolutions against the change (despite the fact they had no legal authority in the matter). Caltech astronomer Mike Brown, who spearheaded the change, wrote in his book How I Killed Pluto and Why it Had it Coming that “I’ve been accosted on the street, cornered on airplanes, harangued by e-mail, with everyone wanting to know: why did poor Pluto have to get the boot? What did Pluto ever do to you?” In 2007, the American Dialect Society recognized the neologism “to pluto” (meaning “to demote or degrade”) as the 2006 Word of the Year.

ITEM: In 2010, paleontologists Jack Horner and John Scannella suggested that Triceratops was just the juvenile form of the longer-frilled dinosaur Torosaurus. Once again, there was public outrage and protests. People complained that their beloved three-horned dinosaur was being snatched away from them. Unfortunately, the public and the media got the story completely backward. IF other scientists eventually agree with Horner and Scannella, and formally decide to ratify the idea that Triceratops and Torosaurus were the same animal, then the invalid name would be Torosaurus, not Triceratops. As Brian Switek pointed out in his blog “Relax—Triceratops really did exist”, Triceratops was named by Yale paleontologist O.C. Marsh in 1889; the same scientist named Torosaurus in 1891. According to the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), Triceratops has priority over Torosaurus, so no one will weep or gnash their teeth if Torosaurus becomes the invalid synonym and is officially demoted. Continue reading…

comments (23)

by

Donald Prothero, May 11 2011

I am a vertebrate paleontologist. I have collected fossil bones out in the Big Badlands of South Dakota and many other places all over the western United States. Although I have collected plenty of dinosaur fossils, I don’t do research on them, but on fossil mammals that are equally cool, including North American rhinoceroses, horses, camels, musk deer, peccaries, and a number of extinct groups that only another mammalian paleontologist would recognize, such as oreodonts and dromomerycids.

People seem to think that my primary job is to collect new fossils and describe them, but in most cases, this is not true. I could spend dozens of man-years getting sunburned in the desert, and not find but a few really scientifically important specimens. Luckily for me and many other paleontologists, there have been many collectors over the past century who have done the hard work in the field, building up large collections in the major museums. What has been missing for a long time is people who want to spend the months and years figuring out what these new fossils are, describing and publishing them, and giving us a correct and up-to-date picture of what fossil animals lived when and where. This is called systematics, and although it’s not as glamorous as the “Indiana Jones”-“Jurassic Park” image of paleontology that most people think of, it is the most important job in paleontology. Without hundreds of hours of careful work in museums, measuring and studying and photographing and then publishing the fossils in highly specialized monographs that only a few people can understand, all the computer-driven arm-waving about how many species lived at a given time, or what caused their extinction (all based on outdated names or incorrect identifications) is “garbage in, garbage out.”

Continue reading…

comments (13)