by

Donald Prothero, Mar 27 2013

The “Lake Pit” in Hancock Park, with the fiberglass mammoth family on its edge. The Page Museum is in the background.

Two years ago this week, I began my weekly contributions to SkepticBlog. It seems amazing to realize that it has been that long, or that I’ve written over 100 essays in that time span. I now begin to appreciate how difficult and stressful it can be, and how newspaper columnists must work, always on the lookout for some germ of an idea to expand into 2000-3000 words. But it’s even harder in a science-based blog, where I’m not just flagging recent stories that I’ve encountered, but also try to write a column of substance full of background that is carefully researched, and adding some of my own scientific perspective on its importance. It’s more like the columns Stephen Jay Gould had to write for Natural History magazine, but he only did them once a month!

Given the occasion, I thought I’d indulge myself and actually blog about some of my own recently published research. I was one of those kids who got hooked on dinosaurs at age 4, and never grew up—except when I was a kid in the 1950s, dinosaurs were not cool with every kid under 12 as they are today. I was the only kid in the school who liked dinosaurs, and I was considered a freak because I knew all about them and could pronounce their names. Now every kid over 7 can do it, apparently. As soon as I knew what a paleontologist was, I knew that’s what I wanted to do. In sixth grade, my teacher Mrs. Helene treated her top boy and girl to a trip out to the Miocene fossil beds at Redrock Canyon (she was a member of the L.A. Natural History Museum, so we got to join her on a member’s tour). By the time I reached tenth grade, I had mapped out where I was going to college and what I was going to study. (I went to U.C. Riverside because it was then cheap for California residents, less than $200 a quarter, not too far from home, yet the large campus had only 4000 students but outstanding geology and biology programs with two paleontologists in the faculty). In the summer after 10th grade (1970), the La Brea tar pits were allowing volunteers to work on their new excavation in Pit 91, and I was eager to join in. As an untrained high school kid, I was relegated to the beginner’s task for all volunteers: sorting out the microfossils (tiny rodent and bird bones, snail and clam shells, insect and plant remains, etc. from the concentrated material left after they wash all the tar out with solvents). They plunked us down on a table beneath a big sycamore tree, and we each had a large lighted magnifier on a stand to see what we were doing hands-free, while we used a tiny wetted paintbrush to pick up these minuscule fossils and place them in the keeper vials. It was dull, tedious work most of the time, but every once in a while we’d find a spectacularly preserved tiny bird bone or rodent jaw, or beetle wing cases which are still iridescent, which made things interesting. I didn’t drive yet, so I had to spend almost 4 hours riding the buses down from Glendale to downtown Skid Row, and then out Wilshire Boulevard and back, just to work for about 4-5 hours a day. But it was lots of fun, and convinced me that no matter how difficult or tedious the work, I was determined to become a paleontologist. Continue reading…

comments (8)

by

Donald Prothero, Jan 30 2013

The tarbosaur specimen poached and smuggled from Mongolia by Prokopi and his partners, and almost sold at auction back in May.

Back on May 23, I posted about the story of a skeleton of the Mongolian tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus that was about to go up for auction. The specimen was a nearly complete skeleton, mislabeled “Tyrannosaurus” to increase its market value, and a major auction house was served with a restraining order just after it had auctioned off the specimen for over a million dollars. The paleontological community had been in an uproar for weeks when the sale was first announced, since it was clearly a smuggled and illegally poached specimen from Mongolia, where no fossil can be removed for sale legally. The Mongolian government, U.S. Customs and Homeland Security, and many others were investigating the specimen. Both American and Mongolian paleontologists pointed out that this species is only known from Mongolia, and furthermore, the matrix around the specimen and its distinctive bone texture and color demonstrated it came from the Nemegt Formation, the only Mongolian formation where tarbosaurs have been found.

Shortly after the story appeared, the sale was stopped pending further investigation. Then the wheels of justice began grinding slowly along as investigators dug into the data about the fossil, tracked down the anonymous “paleontologist” who had procured it, and then supplied the information to our legal system. Just before New Year’s Eve, the story broke that the culprit, poacher Eric Prokopi of Gainesville, Florida, had pled guilty. His sentencing is due in May, and he may get up to 17 years in prison for smuggling contraband into the U.S. Continue reading…

comments (11)

by

Donald Prothero, Jan 02 2013

Buried in all the news of the end of the world, the “fiscal cliff”, and the holiday season was another item that probably escaped most people’s attention. The Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, one of the world’s foremost natural history museums, is planning huge cutbacks in their scientific staff in the next few weeks. Details of who will be cut are sketchy, but the news raced through my professional community and made us all very upset. This is not only because many people who are our personal friends will be losing their jobs because of mismanagement at the top, but also because such a disastrous move would hurt science in many ways that the general public may not appreciate.

First, some background. The Field Museum was founded in 1893 after the Chicago’s Columbian Exhibition of that year ended, and named because of a large endowment from retail mogul Marshall Field (whose stores were a landmark in Chicago until bought out by Macy’s in 2005). It is one of the world’s largest natural history museums, with not only spectacular exhibit halls of dinosaurs and modern animals and gems and minerals and everything else (such as the famous “Lions of Tsavo” and “Tyrannosaurus Sue”), but even larger research collections—almost 400,000 fossil specimens alone! It seemed that such a longstanding landmark would never have trouble, but those of us who have worked in private museums know they are always scrambling for a buck to match their costs, and they are constantly staging fundraisers and schmoozing rich donors with gala events to keep the money coming. A few years ago they seemed to be on top of the world with the coup of acquiring (thanks to huge donations from McDonalds, Disney, and other corporations, not their own money) the famous tyrannosaur “Sue” (now featured in their main hall). But their CEO and trustees apparently made some risky investments, and gambled their endowment on financial instruments that got clobbered in the recession, and now they’re hurting for money. Thanks to the bad decisions of investors, everyone else will suffer (shades of the financial meltdown of 2008). They’ve already cut a lot of other expenses to the bone, fired a lot of the less-skilled support staff, and canceled expensive traveling exhibits. Now they’re about to cut their own hearts out and destroy the staff that makes the museum run in the first place.

Continue reading…

comments (27)

by

Daniel Loxton, Oct 15 2012

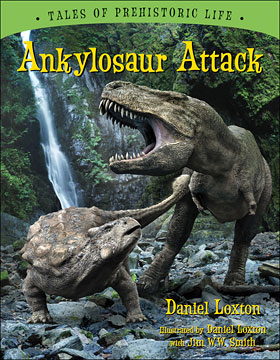

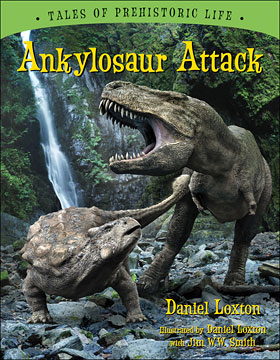

Click for Ankylosaur Attack listing at Shop Skeptic

I’m very excited to announce that Ankylosaur Attack, my first paleofiction storybook for young children (illustrated with Jim W.W. Smith) is among the 2013 Forest of Reading® Silver Birch® Express Award nominees revealed this morning by the Ontario Library Association. This will make the book part of Ontario’s province-wide school and library reading program—the largest such program in Canada.

I’d like to express my immense gratitude to the Ontario Library Association for this nomination (and of course to my publisher, Kids Can Press). The Forest of Reading awards are exceptionally competitive in every category, and it’s an honor to be in such fine company. (My nonfiction Evolution: How We and All Living Things Came to Be was nominated for the Silver Birch nonfiction award, which went that year to my friend Valerie Wyatt—Editor of both Evolution and Ankylosaur Attack, and veteran of over a hundred other children’s books).

Continue reading…

comments (5)

by

Daniel Loxton, Sep 18 2012

Original and revised version of Ankylosaur Attack spread. Click to enlarge and compare. (Popup gallery window will display the original version first. Click “next” on the right side of the popup image to see the revised version. Click “prev” on the left side of the image to jump back to the original version.)

At this point in my life I can claim a few trades. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say I have a reasonable amount of professional experience in sheep herding, in illustration, in writing for kids, or in critical scholarship regarding paranormal claims (or at least certain such claims in specific). But there are many things I’m not—things with which skeptics may sometimes feel more identification than we have expertise. I’m not a psychologist, sociologist, nor doctor, for example. My statements related to those (and indeed most) academic fields should not be considered remotely authoritative.

And despite my children’s books touching on topics of prehistoric life, I’m not a paleontologist.

I care about accuracy in all my work. But although I work hard to get things right in my natural history-informed paleofiction storybooks for kids (Tales of Prehistoric Life, from Kids Can Press), it was probably just a matter of time until some error came to light. That happened when we brought in paleozoologist (and Scientific American blogger) Darren Naish as Science Consultant early in the production cycle for Pterosaur Trouble (the upcoming second book in the series, following Ankylosaur Attack).

Continue reading…

comments (10)

by

Donald Prothero, May 23 2012

The Mongolian tyrannosaur specimen that was to be auctioned off on May 20.

The buzz was going back and forth among my paleontologist colleagues for weeks: an important tyrannosaur skeleton (Tarbosaurus bataar) that had been poached from Mongolia was scheduled to auctioned off on May 20 in New York City. We paleontologists were all outraged, and spent days signing online petitions, blogging, and sending letters and emails to the appropriate parties, but the tiny scientific community of vertebrate paleontologists in the U.S. (no more than 2000 people) don’t hold any real positions of power beyond a handful of museum curator positions and top professorships. But our activity got the attention of the Mongolian government, and they sent formal letters of protest to the auction house and the American government. All the emails and blog posts were full of anger and despair that such blatant theft could be rewarded with a million-dollar sale. Then, just hours before the auction was to start, a Texas judge issued a Temporary Restraining Order, and it appeared that the the fate of the Mongolian tyrannosaur was put on hold. But the auction house went ahead with the sale anyway, getting a final bid over over $1 million, and arguing that the Texas judge has no jurisdiction over a New York auction house. This occurred, even as the attorney for the Mongolian government was in the auction room with the Texas judge on his cell phone, trying to make himself heard and to get anyone to listen to the judge. The sale went on pending resolution of legal issues, so now it is in limbo for a while until this could be sorted out.

This story highlights a much bigger problem that most people never hear about: the huge international market in stolen fossils and antiquities. Bit by bit, some governments are becoming better at protecting their national treasures, but the poachers and smugglers are always much better funded and quicker than even Interpol. Not only is there a big black-market trade in stolen artwork and artifacts, but the market in natural objects is equally brazen and profitable. The stories I’ve heard just want to make you cry! Now that all five species of rhinoceros are nearly extinct in the wild, mounted rhino heads in older natural history museums all over Europe have been stolen or defaced just for their valuable rhinoceros horn (worth more than cocaine or gold by the ounce, all because “traditional Chinese medicine” believe rhino horn reduces fever). Famous fossil localities in protected national parks all over the world are brazenly poached by thieves, destroying not only most of the fossils but ruining the locality for its scientific value as well. Museum research collections and even specimens on public display with security guards and video cameras protecting them are stolen or damaged by thieves. One-of-a-kind fossils that are certainly new species and genera and have the potential to revolutionize our understanding of life’s history are seen briefly and then end up on some rich person’s living room. (Lately, one of the biggest problems is the fad among rich Hollywood celebrities like Nicholas Cage and Leonardo di Caprio to have their own dinosaur in their living room). Even above-board organizations like some major auction houses and the more reputable fossil dealers have to be careful of poached specimens with fraudulent locality data hiding the illegality of their collection. I’ve heard the horror stories from my colleagues who had the proper permits and found an important bone bed on Federal land, only to come back a few days later and someone had plundered the best material and left the rest in broken piles, hacked out of the ground with no attempt to protect the fossil in a jacket—or record the location and stratigraphic horizon of the specimen, which is a big part of its scientific value. It’s common practice now to bury your excavation and hide it once you leave so this doesn’t happen, and I’ve had museums ask me to not publish my GPS coordinates of paleomagnetic sites that also might give away locations of fossil localities. My paleontologist friends in the fossil-rich National Parks are constantly having to spend more and more time planning on how to prevent poaching, and less time doing the science they are better qualified to do. The situation on private land is even messier: although it is usually legal to collect on most privately-held ranches with the consent of the landowner, the story of the tyrannosaur named “Sue” showed that handshake agreements, and disputes over where the specimen was found, and unclear property rights can make those specimens a legal nightmare. Continue reading…

comments (11)

by

Donald Prothero, Apr 25 2012

As someone who has frequently had his scientific research featured in the popular media, I’m painfully aware of the constant struggle between conveying science accurately and trying to make it sexy and newsworthy. Scientists are perpetually frustrated because reporters are often scientifically illiterate, and reduce the story to a level they can understand—which totally misrepresents what the science is about. The science reporters I know are equally frustrated at scientists who don’t know how to communicate the essence of what they are doing, or who are aloof and uninterested in making the public more aware of the reasons why their tax dollars should support pure scientific research. I’ve had my work oversimplified or misrepresented many times, and I’ve seen the work of others completely butchered by incompetent science reporters. I’ve also seen scientists who make outrageous claims and trust gullible science reporters to buy it, hook, line and sinker—and this happens FAR too often (see my April 4 post about the coverage of a ridiculous claim by an amateur that dinosaurs were aquatic, or my Nov.2 post about gigantic Triassic squids arranging ichthyosaur bones).

One of the problems both scientists and reporters face is how to make the research sound interesting to a lay public that knows almost nothing about science—and much of what the public thinks they know is wrong. Much of chemistry and physics is incomprehensible and uninteresting to people that never took a single class in high school on physics or chemistry, and even something more immediate like biology is full of subjects that are obscure to the lay audience. Geologists usually have it slightly better, since topics like earthquakes, volcanoes, landslides, climate change, etc., are easier to relate to.

We paleontologists usually have it even easier, because a few of us work on something immensely popular—dinosaurs—although I’m really a Cenozoic fossil mammal specialist and only rarely has my research ventured back to the Mesozoic. Just add dinosaurs and the research goes to the front page of most science news websites or The New York Times, or gets published in high-profile journals like Nature, Science, or PNAS. But when I make an important discovery on a group such as rhinos or peccaries or camels, I’m lucky to get it published in a third-tier journal, and I typically get no reporters calling at all. The Cretaceous-Tertiary extinctions that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs generated huge interest when the asteroid impact theory first emerged in 1980, with thousands of papers published and dozens of books on the topic. But it’s only the third or fourth largest extinction in earth history. The great Permian extinction 250 m.y. ago, which wiped out 95% of species on earth, is lucky to get ANY press attention. Who cares about productid brachiopods, or fusulinids, or tabulate or rugose corals, among the many victims of this event? Continue reading…

comments (20)

by

Donald Prothero, Mar 07 2012

Last Feb. 11, the day before Darwin’s 203rd Birthday, I was invited by Ross Blocher and Carrie Poppy of the “Oh, no, it’s Ross and Carrie” podcast to accompany them, along with Emery Emery and Heather Henderson of the Ardent Atheist podcast, to visit the Creation Museum in Santee, east of San Diego, California (videoblog available here). This museum was originally built by the Institute of Creation “Research” (ICR), once led by the late Henry Morris and Duane Gish, which has since relocated to Texas. At one time ICR was the leading creationist organization in the U.S., but lately they seem to have lost their influence (they couldn’t even get their school accredited in conservative Texas!). Now they are overshadowed by Ken Ham of Answers in Genesis and his multi-million-dollar creation museum in Petersburg, Kentucky (which I saw back in 2009). When ICR left California, they sold their museum to Tom Cantor, who made his fortune with a biotech firm, Scantibodies Laboratory, Inc. Cantor bills himself as a Jew converted to creationism, and gives away free DVDs of his story (complete with the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem in the background) subtitled “A Message of Hope and Gladness for the Jewish people”! With the new ownership, the drab building in an industrial park that long housed the creation museum is now shared with Scantibodies. In one of the many ironies of the place, Scantibodies Inc. makes antibodies, blockers, serum, plasma, and other medical kits, all of which demonstrate the process of evolution in action, and require evolutionary principles to work with….

Emery Emery and Heather Henderson mug in front of the tail-dragging T. rex in front of the drab industrial building that houses the museum.

You arrive and drive through heavy black iron gates and walk past a few cheesy dino sculptures in front. These include a miniature T. rex based on the outdated concept with tail dragging behind it. (At least they don’t claim that the predatory dinos ate coconuts. not meat, with their long sharp teeth, as Ken Ham’s museum does). There is a Galapagos tortoise model, a small ankylosaur, and a replica of a dinosaur egg nest, with the false statement that dinosaurs did not take care of their young (long ago debunked by Jack Horner’s Maiasaura nests in Montana). Once inside, there is a lobby with a reception desk and a gift shop which has more products from Ken Ham’s organization than it does from the old ICR gang. The docent that Ross and Carrie wanted to interview was already inside giving a tour, so we headed right in.

Continue reading…

comments (34)

by

Donald Prothero, Feb 15 2012

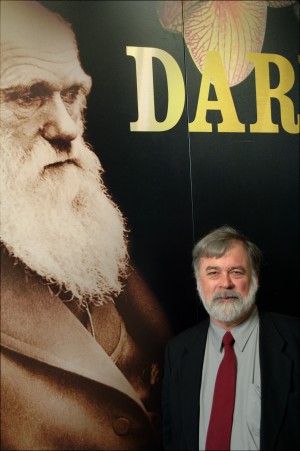

Niles Eldredge as he looks today, Curator Emeritus at the American Museum of Natural History

Experimental biology … may reveal what happens to a hundred rats in the course of ten years under fixed and simple conditions, but not what happened to a billion rats in the course of ten million years under the fluctuating conditions of earth history. Obviously the latter problem is more important.

—George Gaylord Simpson, 1944, Tempo and Mode in Evolution

Last Sunday, Feb. 12, we celebrated the 203rd birthday of two of the most important figures in world history, Abraham Lincoln—and Charles Darwin. To mark the occasion properly, I spent part of my weekend visiting the Creation Museum in Santee, California, with Carrie Poppy and Ross Blocher of the podcast “Oh no, Ross and Carrie!” (more on that trip in my March 7 post). But I thought I’d mark this anniversary with a discussion of another important anniversary in the history of evolutionary science.

(left to right) Stephen Jay Gould, Michael Shermer, and yours truly, Mt. Wilson Observatory, 2001

It was 40 years ago this year that the most frequently cited paper in the history of paleontology was published. That was none other than the legendary 1972 article by Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould which proposed the “punctuated equilibrium” hypothesis. (Full disclosure: I took seminars from Niles while I was a student at the American Museum of Natural History, and Steve Gould was very interested in and supportive of my research even though I was not his student in a formal sense). At the time the paper came out, the dominant concept about speciation was the allopatric speciation model. In a nutshell, good biological evidence showed that new species arise not in the large mainland populations (with their extensive gene mixing) but in small isolated populations with unusual gene frequencies (peripheral isolates), usually living separate (allopatric) from the mainland population. Once these allopatric populations were no longer isolated but remixed with the mainland population, they would be genetically and behaviorally distinct from their parent species. Thus, they would be no longer capable of interbreeding, which is part of the definition of a biological species.

Even though the allopatric speciation model was accepted by biologists as early as 1942, it took paleontologists 30 years to recognize its implications. In their historic 1972 paper, Niles and Steve pointed out that if you took Ernst Mayr’s allopatric speciation model seriously, it would predict that species should arise in a normal biological time frame: a few years to a few hundred years at most. That’s a geologic instant, the difference between one bedding plane and the next in strata that span millions of years. The allopatric speciation model also predicted that species should arise in small, peripherally isolated areas, so they were unlikely to be fossilized in the few places for which we have a good fossil record. Rather than slow gradual change through millions of years of strata (the “phyletic gradualism” model), the allopatric speciation model accepted by biologists should give a fossil record where species seem to appear suddenly without any gradual transition preserved (“punctuation”), and then persist for long periods of time without change (“equilibrium”). Continue reading…

comments (11)

by

Donald Prothero, Nov 23 2011

JIngmai O'Connor '04 collecting fossils in the Triassic Ichigualasto Formation, Argentina

A teacher affects eternity; he can never tell where his influence stops.

—Henry Adams

In teaching you cannot see the fruits of a day’s work. It is invisible and remains so, maybe for 20 years.

—Jacques Barzun

Having taught at small liberal arts colleges (first Vassar, then Knox College in Illinois, now Occidental College in Los Angeles and also Caltech in Pasadena) for over 30 years now, I’ve experienced all sorts of highs and lows. Sure, there are the bored unmotivated students, the nasty administrators and colleagues, the grind of teaching all my own labs with no help, and teaching the same intro courses year after year, the low pay for long hours with no support for research, the difficulty of getting any time off from teaching to attend essential professional meetings. But there are also the pluses: flexibility of schedule, freedom to teach what I want to teach with minimal interference from above, the small classes where I really get to know the students, and can make sure they understand the material,

But the best benefit of all is the outstanding students who want to do research as undergrads. Since we have no grad program, for years I’ve been treating undergrads as grad students and getting them involved in research. I include them in my field crews or museum research trips (where they find their own projects), help them attend professional meetings and do their own presentations, and help them publish their research. I’ve had many such students over the years, including over 50 different student coauthors on quite a few of my papers. Some, like John Foster ’89, have made it professionally (he’s Curator of Paleontology at the Museum of Western Colorado), and many others are working in environmental or energy firms, earning twice what I make. One never knows how you change the lives of your students when you work closely with them. Of the recent grads, Linda Donohoo-Hurley ’00 finished her Ph.D. at Univ. New Mexico—and I inadvertently introduced her to her future husband, John Hurley, when she presented our research at a Penrose Conference I organized. Others are about to finish their doctorates. These include Jonathan Hoffman ’03, who came specifically to study with me (M.A. at Florida, nearly done with his Ph.D. at Wyoming); Josh Ludtke ’04. who took care of my eldest son at times (M.S. at San Diego State, finishing his Ph.D. at Univ. Calgary); and Kristina Raymond ’08, just finishing her master’s at ETSU. Our program is small (only 3-7 graduating geology seniors each year, yet we have 5 full-time tenured faculty), but we turn out a lot of good grad students per capita.

Continue reading…

comments (12)