Losing our religion

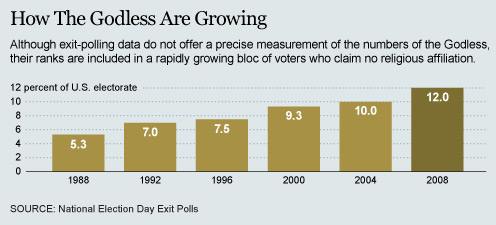

In previous posts, many of the contributors to this site (along with many scholars of religion in America) have commented on the steady decline in organized religion, especially the decline in the evangelical and fundamentalist churches. The same studies have also shown a remarkable increase in the “religiously unaffliated”, not only atheists and agnostics, but also those who say “nothing in particular” when polled about their religious affiliation and beliefs. According to a Pew study released last October, the “unaffliated” are now about 20% of the general population, outnumbering nearly every other group (Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, Mormons, and most Protestant denominations) by a big margin (each of the rest of these groups is 2% or less of the population). Only the Catholics and the Southern Baptists are still more numerous, and both of these are losing ground. And those who said that they had “nothing in particular” in the way of affiliation, 88% also said they were “not looking.” Thus, the decline in religiosity across the board in the U.S. is not some sort of hippy-dippy movement to “New Age” religions from the old stale Protestant churches—but a movement away from any form of organized religion.

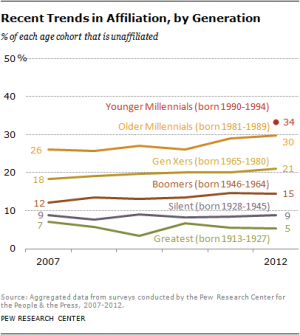

Even more striking is how this breaks down demographically. The most remarkable of the trends is how much it is stratified by age. Young people are becoming decreasingly religious, so much so that the youngest cohort (the “Young Millennials,” born 1990-1994) are 34% non-religious! About 30% of the “Older Millennials” (born 1980-1989) are also non-religious, while the “Gen Xers” (born 1965-1980) report 21% “unaffiliated”, so the percentage declines only very slightly as the cohorts age. All of these people together contribute to the overall 20% of “unaffiliated” in the poll, and will increase through time. Clearly, organized religion is fading rapidly in this country, driven by a combination of young people who see no need of it, and the dying off of the older generations that were raised in a strongly religious society. As sociologists like Phil Zuckerman have shown, such trends have already happened to most of the western industrialized nations (especially those in Scandinavia), as the benefits of a modern secular society and modern medicine and science become more central to their lives.

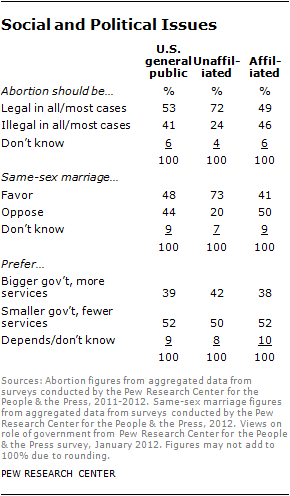

The percentages of “unaffiliated” vs. religious people who support or reject various key political causes

We can all speculate about why younger generations are alienated from organized religion, and certainly there are many reasons. But knowing the current political trends in this country, we might suggest that one factor of great importance is how “organized religion” in this country is largely driven by the shrill and intolerant evangelicals (including the extreme Catholics like Rick Santorum), and their hate-filled message against gays, women, and sometimes minorities. This showed up clearly in the demographics of those who voted for Obama vs. McCain and Obama vs. Romney in the past two elections. With the incredibly rapid shift in this country toward majority acceptance of gays (who are overwhelmingly supported by young people, among whom homophobia and religious intolerance is rare), it might seem that such an issue is driving people away from religious zealots in politics, and their causes. Sure enough, that is confirmed by recent polling. The Pew Study cited above shows almost mirror image percentages: those who are “unaffiliated” are largely supportive of gay rights and abortion rights; those who are religious are just the opposite. Another study drives the point home in stark relief. The single biggest factor driving people away from churches is indeed the intolerance and hatred shown by the evangelicals, and how they have manifested this whenever they have secured political power. As The Los Angeles Times describes it, this is a striking change from only 30 years ago:

During the 1980s, the public face of American religion turned sharply right. Political allegiances and religious observance became more closely aligned, and both religion and politics became more polarized. Abortion and homosexuality became more prominent issues on the national political agenda, and activists such as Jerry Falwell and Ralph Reed began looking to expand religious activism into electoral politics. Church attendance gradually became the primary dividing line between Republicans and Democrats in national elections.

This political “God gap” is a recent development. Up until the 1970s, progressive Democrats were common in church pews and many conservative Republicans didn’t attend church. But after 1980, both churchgoing progressives and secular conservatives became rarer and rarer. Some Americans brought their religion and their politics into alignment by adjusting their political views to their religious faith. But, surprisingly, more of them adjusted their religion to fit their politics.

We were initially skeptical about that proposition, because it seemed implausible that people would make choices that might affect their eternal fate based on how they felt about George W. Bush. But the evidence convinced us that many Americans now are sorting themselves out on Sunday morning on the basis of their political views. For example, in our Faith Matters national survey of 3,000 Americans, we observed this sorting process in real time, when we interviewed the same people twice about one year apart.

For many religious Americans, this alignment of religion and politics was divinely ordained, a long-sought retort to the immorality of the 1960s. Other Americans were not so sure.

Throughout the 1990s and into the new century, the increasingly prominent association between religion and conservative politics provoked a backlash among moderates and progressives, many of whom had previously considered themselves religious. The fraction of Americans who agreed “strongly” that religious leaders should not try to influence government decisions nearly doubled from 22% in 1991 to 38% in 2008, and the fraction who insisted that religious leaders should not try to influence how people vote rose to 45% from 30%.

This backlash was especially forceful among youth coming of age in the 1990s and just forming their views about religion. Some of that generation, to be sure, held deeply conservative moral and political views, and they felt very comfortable in the ranks of increasingly conservative churchgoers. But a majority of the Millennial generation was liberal on most social issues, and above all, on homosexuality. The fraction of twentysomethings who said that homosexual relations were “always” or “almost always” wrong plummeted from about 75% in 1990 to about 40% in 2008. (Ironically, in polling, Millennials are actually more uneasy about abortion than their parents.)

But Hemant Mehta argues that the regressive social policies of fundamentalists isn’t the only factor. He points to the fact that younger generations are more likely to learn from the internet, and less likely to obey everything their parents tell them, especially when they have questions that organized religion has no good answers for. Certainly, the virtual community of web-enabled young people can explore and learn about topics like atheism and evolution in a way that would have been impossible in many small religious American towns just a generation ago. Even if the social pressure of the conservative community censors or hushes up these topics in school and at the library, the internet opens a window that cannot be shut by local authorities—and younger people are more likely to find their own answers this way than ever before.

For those of us who value science and science education in this country, this is good news. As I’ve argued in several previous posts, the single biggest factor that causes us to fall behind nearly all the other westernized industrial nations (including Japan, South Korea, China, and Singapore, along with most of Europe) is religion. When you break down the polling, it’s always questions about evolution, the age of the earth, cosmology, and human evolution that nearly always cause Americans to flunk science literacy tests compared to other nations. These are all questions that reflect the creationist-evangelical influence on our culture. Thank gods, it is apparently declining. It probably won’t become Denmark in the U.S. during my lifetime, but I’m optimistic that the never-ending battles with creationism in the U.S. will gradually end as all the old evangelicals die off and they are not replaced by a comparable cohort of the younger generation that was similarly brainwashed. One can only hope…

Unfortunately, a less optimistic, but equally plausible, interpretation of the first chart is that people become more religious as they grow older. Superficially, the second chart contradicts this interpretation, but it too could be confounded by age.

But what the studies I cited show is that younger people are non-religious at a MUCH higher rate than they were just a generation ago. Some will indeed become more conservative and religious as they get older, but there has been a HUGE drain of young people away from churches in this country–and that’s unlikely to reverse itself (as we see in the non-religious countries of western Europe). It’s just a question of how quickly it will happen–in a generation or two, like Quebec and northern Europe, or over a longer time.

I was the last person I knew to realize I was an atheist. Finally, at some point in my fifties (ah, youth), a friend described me as his favorite atheist. That surprised me. I thought about it a while and realized he was right. It wasn’t that I’d had some sort of reverse revelation (even though I was raised in a religious household). It’s just that I hadn’t cared enough to even think about it for a couple of decades. It’s not like there was some great aching hole that had to be filled. I wonder if it’s that way for a lot of people. When religious people get their claws into you, it’s like you’re supposed to worry about it. But if they never gain a purchase, you’re more likely to spend your energy thinking about things that matter.

The answer to the question “Do you believe in God” is “Huh?”.

It’s not just Pew that reports this, it’s also ARIS and Gallup.

I’ve also seen age breakdowns for previous years, and each generation seems to have the same average amount of religiosity for most of its life.

What’s happening is much like what’s happening in Europe: more and more people getting decoupled from organized religion and staying that way, despite whatever affiliation they may continue to profess.

Trends can reverse. Russia is religious now, not that it was much more tolerant or less homophobic in the Soviet days. Christianity is growing in China. France is up to 10% Muslim. Turkey turned more Islamist, with six out of ten people believing in the need for more religious facts instead of science. Israel is becoming more religious because of high birthrates in religious families. An influx of Mexican immigrants may boost Catholicism in the U.S.

True–but I specifically said “western Europe and westernized Asian nations like Japan, Singapore” etc. Christianity is still TINY in China, and I can’t imagine the Communist leadership letting it become a threat. As Phil Zuckerman and others have shown, the trend in Western Europe among non-Muslims is NOT reversing but becoming more secular in every generation.

According to this, there are 60 million Christians in China.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-14838749

Whether that’s “tiny”, I couldn’t tell you.

And I’ll just add that it speaks volumes that a supposedly serious person looks joyously at the prospect that the Communist party will do something before religion becomes “a threat”. You would have made an excellent addition to the NKVD.

The biopsychologist Nigel Barber believes that atheism is increasing globally as people have more material security. The most religious areas such as sub-Saharan Africa are also the poorest. See http://www.medicaldaily.com/nigel-barber-predicts-religion-will-be-irrelevant-most-2041-says-belief-just-way-control-uncertainty

The USA seems somewhat an exception since it’s affluent and also most people here claim to be religious. But Barber points out that there’s a lot of income inequality here, the USA doesn’t give its citizens as much security as do atheistic countries like Sweden and Japan. Also, a lot of people in the USA exaggerate their church attendance. The actual figures for church attendance in the USA don’t match with people’s claims.

Exactly! This trend has been noted by a LOT of people in the sociological community. See the excellent books by Phil Zuckerman on the topic.

China is a country that is becoming more Christian, while at the same time becoming more prosperous, or “materially secure”, and, supposedly anyway, is eating the US’s lunch when it comes to scientific research.

Hmm, maybe the thesis is incorrect, and the “sociological community” tends to conclude whatever it wants to.

Phil Zuckerman and others propose a difference between the officially imposed atheism of Communist countries and the “organic” atheism of many industrialized countries. It’s the latter that is growing, even if the former has not necessarily been growing.

I fit the Pew Forum’s numbers to a bent line, and here is what I found:

For people born in 1969, the unaffiliated fraction was 19%. For people born before that date, the fraction increased by about 0.29%/year, and for people after that, about 0.67%/year.

Someone born in 1969 came of age in the mid to late 1980’s, not long after the Religious Right became prominent. This seems to agree with the Religious-Right repulsion theory.

What’s curious here is the lack of a prominent Religious Left. Where did it go?

The Religious Left is “undocumented” ;-)

I also believe the last three contested Democratic primaries had a “Reverand” in the mix.

“When you break down the polling, it’s always questions about evolution, the age of the earth, cosmology, and human evolution that nearly always cause Americans to flunk science literacy tests compared to other nations.”

Again, you are wrong, per one of the very sources you cited in one of your previous posts:

“A slightly higher proportion of American adults qualify as scientifically literate than European or Japanese adults, but the truth is that no major industrial nation in the world today has a sufficient number of scientifically literate adults,” he said. “We should take no pride in a finding that 70 percent of Americans cannot read and understand the science section of the New York Times.”

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/02/070218134322.htm