She Protects Planets

One of the great pleasures of writing Junior Skeptic is getting to answer the questions that bother me at the back of my mind—the questions I daydream on the bus, that fill me with excited curiosity when I should be settling into sleep. Another great pleasure is the discovery that scholars and scientists are extraordinarily generous with their time.

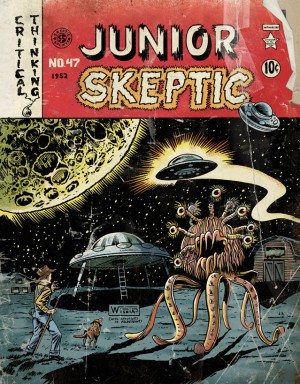

When I sat down to write the current Junior Skeptic, “Alien Invaders!” I was reminded of something that had long bugged me: is anyone concerned that our spacecraft might carry microbes that could contaminate other worlds? After all, bacteria are tough little buggers. And—consider The War of the Worlds as a cautionary tale. What if returning spacecraft carried dangerous microbes back to Earth? Could alien bacteria devastate our own planetary ecosystem, as H. G. Wells imagined terrestrial bacteria annihilating his Martians?

Turns out that there are people whose job it is to worry about those hypothetical contamination dangers—and to work to prevent them. With some pointers from Bad Astronomy’s Phil Plait and the Planetary Society’s Emily Lakdawalla, I soon learned that this is an entire field that dates back to the first tentative human steps beyond the Earth.

Planetary Protection

The work of preventing or minimizing contamination between bodies in space is called “planetary protection.” With the launch of Sputnik I and II in October and November of 1957, it became clear immediately to everyone that the Space Age was going to unfold in a hurry. Scientists realized that the nationalistic need to rush into space could badly conflict with the scientific point of going there. If human actions permanently altered the environments we were visiting through the introduction of microbes, exotic gases, or radioactivity, how could we study those environments? We wouldn’t know what was natural, and what was artificial. And, after all, pristine environments are only pristine once. We had to get it right the first time.

All the same, given Cold War antagonisms, it’s astonishing to me that the major players in the space race—and soon most of the nations of the Earth—agreed very quickly that space exploration should be conducted in such a way as to minimize environmental damage. This widely-shared concern did not reflect any soft-hearted green ideal, but pure scientific pragmatism. Scientific committees, international treaties, and offices within NASA and other space agencies quickly formed to work out protocols for what came to be called planetary protection. Should spacecraft be sterilized? How sterile is sterile? How do you sterilize the hidden surfaces of the screws holding delicate sensors in place? What about spacecraft that merely pass near a planet? Should all bodies be protected, or just the ones where life might have (or gain) a toehold? The ideal is simple, but the details are complex.

The story of how this unfolded is told admirably by Michael Meltzer’s 2011 book When Biospheres Collide: A History of NASA’s Planetary Protection Programs, published by NASA—and, happily, available in its entirety for free in PDF and other formats!

Dr. Catharine “Cassie” Conley, NASA’s

Planetary Protection Officer

She Protects Planets

Today, NASA has an Office of Planetary Protection to ensure compliance with planetary protection requirements—which is mandatory for every NASA mission design.

The person in charge of that work—NASA’s Planetary Protection Officer—is Dr. Catharine “Cassie” Conley. Dr. Conley was kind enough to take time from her schedule to help me with my fact-finding for Junior Skeptic. Her answers were so generous, and this topic so fascinating, that the short quotes I could include in the Junior Skeptic story barely scratched the surface. I asked her permission to share her answers here in greater length, with the understanding that I emphasize that this was an informal email exchange. My thanks once again to Dr. Conley for sharing her time and expertise.

Junior Skeptic: Do you think there ought to be an ethical component to Planetary Protection? Ought we to care about pristine extraterrestrial ecosystems for their own sake, in your opinion?

Conley: Planetary protection, as practiced over the past 50+ years, focuses explicitly on biology and the search for life, so in that context we don’t have significant concerns about what happens in places where biology does not. However, the COSPAR Panel on Planetary Protection was instrumental in supporting the formation of another COSPAR panel, the Panel on Exploration, where those sorts of ethical considerations are addressed—as well as historical preservation concerns, like damage to Apollo sites through access by later missions. The hardware belongs to NASA, but what about the footprints?

I consider questions of environmental and historical preservation, including particularly the ethical context of human activities in space, to be very important—but formally they’re not a part of biological planetary protection as practiced over the past 50+ years. We need park rangers as well as policemen, but it’s not necessarily the right approach to have one organization doing both.

COSPAR, as background, is the venue where international planetary protection policy is set—the COmmittee on SPAce Research is a standing committee of the International Council for Science (ICSU) that advises the UN on scientific matters, just as national science academies advise national governments. COSPAR advises the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, which is responsible for the 1967 Outer Space Treaty—the COSPAR Panel on Planetary Protection maintains policy supporting compliance with Article IX of the OST, which covers “harmful contamination” of planetary bodies and “adverse changes to the environment of the Earth” resulting from from the introduction of extraterrestrial matter.

The major national space agencies (e.g., NASA, ESA and affiliated national space agencies, RosKosmos, JAXA, ISRO) have agreed to follow COSPAR policy on international missions—this forms a framework under which all national space exploration is carried out using the same rules.

Article VI of the OST specifies that States Parties to the Treaty are responsible for the actions of non-governmental entities, so this means that commercial activities are already covered by national responsibilities.

Making sure that everybody in the various communities understands this, however, is a bit more of a challenge….

Junior Skeptic: What role might Planetary Protection play in a manned mission to Mars? Does the concept become obsolete once humans step onto Mars?

Conley: Planetary protection is at least as important on human missions as it is on robotic missions, because in most cases we expect the astronauts to come back to Earth. This means that a lack of attention, if Mars does have life that can survive and spread on Earth, might result in significant “adverse changes to the environment of the Earth”—which would affect everyone on this planet. We’ve demonstrated the environmental consequences of moving invasive Earth species from one location to another, at least enough to realize that preventing Mars life from doing the same would be a very good idea…

COSPAR established guidelines and policy for human missions to Mars in 2008, after a nearly decade-long process of meetings and scientific/engineering/technical discussion about what makes sense and what is possible to do. From the policy standpoint we have the same objectives—don’t contaminate Mars and don’t contaminate the Earth—but we’ll have to go about meeting those in somewhat different ways. It’s possible to engineer human support systems such that they release only limited biological contamination into the Mars environment—this is exactly what closed-loop life support systems try to do, because cost and mass are reduced the more the support systems can recycle materials internally.

The overall approach on planetary protection for human exploration of Mars has three prongs, if you will: minimize release of human-associated contamination to locations on Mars where Earth life could survive; minimize exposure of humans to uncharacterized Mars materials; and monitor human health and the microbial populations associated with humans and support systems, in order to identify any perturbations to those indicators that might suggest exposure of the astronauts to possible Mars life.

In support of this last activity, which we don’t have to do for robotic missions, it will be very important to develop and test such microbial and human health monitoring systems on missions to other planetary bodies, such as the Moon and asteroids, where we don’t expect to find local life—in that way, we can assemble a body of information about how humans interact with non-living planetary materials, such that if we document only similar/equivalent changes on Mars missions then we increase confidence that we can justify bringing even a sick astronaut back to Earth.

If an astronaut gets sick after exposure to Mars materials, and we don’t have this supporting information, then it might be rather difficult to convince the rest of the planet to allow return—maritime law for centuries has allowed ports to tell a ship to go back to the previous port of origin.

Junior Skeptic: Does NASA’s Planetary Protection Office have a role to play in (or jurisdiction over?) private space travel?

Conley: Under the NASA Authorization Act, as amended, section 203(c)8 authorizes NASA to coordinate our activities with scientific and other activities carried out by public and private organizations. NASA is not a regulatory agency within the US government, but NASA does provide expert input to other regulatory agencies, for example the FAA launch certification process. What mechanisms the US could use to regulate activities that happen outside the Earth’s atmosphere is still in work.

Junior Skeptic: And this one, suggested by conversation with kids about this topic: Should we be scared about getting sick from dangerous germs from outer space?

Conley: We don’t know whether living organisms exist anywhere else than the Earth. What we do know about Earth germs is that they generally infect only a small subset of organisms, because they have all grown up together and evolved the capability to be infectious. For this reason, it’s quite unlikely that organisms evolving somewhere else would somehow coincidentally be able to infect humans. There aren’t any humans on other planets yet, for those organisms to interact with.

Although this is very unlikely, planetary protection does explicitly address the possibility that astronauts could get infected by life from elsewhere—in that case, we’d have to be very careful about bringing them back to Earth.

A more likely, but still remote, possibility is that Mars organisms might find specific locations on Earth to be pleasant, and by growing there could change the environmental conditions on Earth—like rabbits in Australia eating all the grass. Mars organisms might think that the Antarctic is a wonderful warm pleasant place—if they were to grow on top of the ice sheets and absorb more sunlight, that might cause faster melting.

We don’t expect that Mars organisms could cause harm to the Earth, but the policies of planetary protection are designed to ensure we take appropriate precautions even against unlikely events—that’s the only way to be responsible to the people and environment of the Earth, as humans explore space.

Like Daniel Loxton’s work? Read more in the pages of Skeptic magazine. Subscribe today in print or digitally!