“Testable Claims” is Not a “Religious Exemption”

Today I thought I might share a short excerpt from my two-chapter “Why Is There a Skeptical Movement?” on the topic of scientific skepticism’s long-standing focus on testable claims (particularly those related to the paranormal or fringe science). It’s an issue that is in the air at the moment following a fantastic speech delivered by magician Jamy Ian Swiss at the Orange County Freethought Alliance conference last weekend. You can view the entirety of Jamy’s speech on YouTube. (For more on the conference, see Donald Prothero’s post here at Skepticblog.)”Why Is There a Skeptical Movement?” was almost two years in the making. As the Skeptics Society has shared it for free, the historical research alone may be worth your price of admission. I do hope you’ll consider delving further into the story of scientific skepticism’s long and proud public service tradition—the work of decades, even centuries, of activism and investigation. But this particular “testable claims” point is so critical to the understanding of skepticism, and so frequently not understood, that I feel that sharing this section from the piece here may be useful. With yet another ghastly news story again raising the question of predatory paranormal fraud, this may be a good time to say once again that the need for this work—the need for clarity, focus, and sustained, dedicated effort—is as urgent as it has ever been. I hope you will support skeptics in doing that work, even if your own primary cause is not the same.

“Testable Claims” is Not a “Religious Exemption”

Skeptics like Steven Novella insist that sticking to the realm of science is “about clarity of philosophy, logic, and definition”1 rather than strategic advantage or intellectual cowardice,2 but some critics find this position unsatisfying—or even suspicious. What are we to make of accusations that skepticism’s “testable claims” scope is a cynical political dodge, a way to present skeptics as brave investigators while conveniently arranging to leave religious feathers unruffled? Like the other clichés of my field (“skeptics are in the pocket of Big Pharma!”) this complaint is probably immortal. No matter how often this claim is debunked, it will never go away.

Nonetheless, it is grade-A horseshit. It’s become a kind of urban legend among a subset of the atheist community—a misleading myth in which a matter of principle is falsely presented as a disingenuous ploy. There is (and this cannot be emphasized enough) no “religious exemption” in skepticism. Skeptics do and always have busted religious claims.

That’s so important and so often misunderstood that I’m going to repeat it: collectively, scientific skepticism has never avoided claims because they are religious in nature—not for political expediency, not to “coddle” anyone, and not for any other reason. As magician Jamy Ian Swiss (founder of the New York Skeptics) explained in a thundering main stage speech at the James Randi Educational Foundation’s Amazing Meeting 2012 conference, the notion that skeptics grant religion “any sort of special pass…is not only a weak position, I don’t think it’s a real position. It’s an imaginary one. It’s one I only seem to hear or see as a straw man that atheist activists accuse skeptics of promoting.”3

Let me amplify that still further: anyone who makes the argument that the testable claims scope is a deliberate ploy to “avoid offending the religious” is either unfamiliar with the literature of scientific skepticism, or chooses to misrepresent it.

Now, here’s what actually is true: scientific skeptics investigate claims that can be investigated (religious or otherwise) and we set aside claims that cannot be investigated (again, religious or otherwise). The “religious” part is irrelevant. It comes up on both sides of the testability equation, so just cross it out and forget about it. The only relevant distinction is simply whether empirical evidence is possible. If we can’t collect evidence, then tough—we can’t. If we can collect evidence, then we do, regardless of whom that evidence may offend.

“If someone says she believes in God based on faith,” clarified Michael Shermer, “then we do not have much to say about it. If someone says he believes in God and he can prove it through rational arguments or empirical evidence, then, like Harry Truman, we say ‘show me.’”4

Skeptics have always been willing (and often eager) to confront central tenets proclaimed by venerated religious leaders—claims considered sacred and profound matters of faith by many sincere people—when any concrete, scientifically meaningful claim is advanced.

The textbook example of the testable claims scope applied to religion by scientific skeptics is James Randi’s exceedingly public humiliation of Peter Popoff, a popular Christian minister. Popoff’s multi-million-dollar ministry was built on his reputation as a faith healer who received (it appeared) miraculous knowledge about the medical health and personal details of the faithful in the audience.

Where an atheist activist might have railed against the a priori implausibility of these performances, Randi and his allies (from the Houston Society to Oppose Pseudoscience,5 the Society of American Magicians, and the Bay Area Skeptics6) instead took scientific skepticism’s much more concrete path: they broke Popoff’s schtick down to its testable components, and then literally tested them.

This point is worth highlighting. A lot of the work of “scientific skepticism,” such as my own historical sleuthing, is “scientific” only in the broadest sense: it is critical, evidence-based, and works within an empirical framework. But Randi’s 1986 Popoff investigation involved direct hypothesis testing (and, hell, even machines that go beep). Setting aside untestable metaphysical speculations, Randi’s team hypothesized that Popoff’s information was harvested directly from the audience. They tested this by seeding the audience with skeptical activists. Randi explained that before his dedicated group of volunteers distributed themselves throughout the audience,

I instructed them to allow themselves to be approached, and to give out incorrect names and other data whether they were “pumped” by questioners, asked to fill out healing cards, or both. They were told to supply slightly different sets of information to the two data inputs, so that if any of them were “called out” we could tell from the incorrect information just which method had been used.7

Sure enough, Popoff called out Randi’s people by their false names, and fed back their planted, bogus information. Armed with this result, Randi and his colleague Steve Shaw (a skeptic and professional magician who performs under the name Banachek) further hypothesized that this information was passed to Popoff electronically.

When Steve and I saw Popoff dashing up and down the aisles calling out as many as 20 names, illnesses, and other data, one after the other, we knew something more than a mnemonic system was at work. I said to Steve, “You know what to do?” He replied: “Yep. I’ll go look in his ears.” And he did, almost bowling the evangelist over as he bumped up against him to get a good look. Steve saw the electronic device in Popoff’s left ear. When he reported this to me, I knew what my next step would be.9

The following week, Randi, the Bay Area Skeptics, and an electronics specialist named Alexander Jason were ready for Popoff’s performance in San Francisco. The night before Popoff’s event, Jason scanned the radio frequencies active at the same auditorium. With those frequencies saved and filtered out, Jason and Bay Area Skeptics founder Robert Steiner were easily able to dial in to the Popoff operation’s radio frequency.10 Tape rolling, the team recorded Popoff’s wife secretly feeding him harvested information about members of the audience, which he fed back to the audience as an apparent miracle. Popoff was caught red-handed.

Randi revealed this incontrovertible evidence on network television, on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, airing videotape from the Popoff event with the secret radio transmission overlaid for the television audience to hear. Ouch. The scandal broke the back of this popular Christian ministry: Popoff declared bankruptcy in 1987. (After a period of humiliated obscurity, Popoff built a new ministry—now even more profitable. Randi reflected in a 2007 Inside Edition interview that this was not surprising: “Flim flam is his profession. That’s what he does best: he’s very good at it, and naturally he’s going to go back to it.”11)

Scientific skeptics accept scientific limits. These limits are not conjured up to annoy people, nor adopted for strategic convenience; they’re simply baked into the nature of science. “If it is not measurable even in principle,” Michael Shermer explained, “then it is not knowable by science.”12

Contrary to common misconception, this empirical standard is not something skeptics apply only to claims that are considered sacred in modern traditions. The exact same scientific/non-scientific distinction applies to all claims, regardless of their content. Steven Novella explained yet again in 2010, “It is absolutely not about ghosts vs holy ghosts…. Any belief which is structured in such a way that it is positioned outside the realm of methodological naturalism by definition cannot be examined by the methods of science.” Novella went on: “The content of the beliefs, however, does not matter —it does not matter if they are part of a mainstream religion, a cult belief, a new age belief, or just a quirky personal belief. If someone believes in untestable ghosts, or ESP, or bigfoot, or whatever—they have positioned those claims outside the realm of science.”13 Science is not able to demonstrate that undetectable metaphysical ghosts do not exist; only that detectable ghosts appear not to, and that many alleged hauntings have other explanations. We cannot determine whether or not homeopathic preparations are really “dynamized” with undetectable vitalistic energy; we can discover whether they have greater treatment effects than a similarly administered placebo. We can’t demonstrate that we ought to value liberty above the common good, or value security over liberty. We can’t demonstrate that taxation is slavery, or that the means of production should be in the hands of the worker. We can’t demonstrate that there is no afterlife, or that gay marriage is morally good, or that Kirk is better than Picard. We cannot demonstrate that Carl Sagan’s neighbor has no invisible, undetectable dragon in his garage—but only proceed, as a methodological matter, on the basis that we are unable to discern any difference between an undetectable dragon and no dragon at all. Are untestable dragons ontologically identical to non-existent dragons? That’s a question for bong hits in freshmen dorms. Science can’t tell, and doesn’t care.

Individual skeptics may have opinions about all those philosophical matters, but none of these are questions science can answer. As Novella and Bloomberg explained [in a well-known 1999 Skeptical Inquirer article], “science can have only an agnostic view toward untestable hypotheses. A rationalist may argue that maintaining an arbitrary opinion about an untestable hypothesis is irrational—and he may be right. But this is a philosophical argument, not a scientific one.”14

Irrational or not, like everyone else, I hold many strong and (I feel) well-reasoned philosophical opinions. Those are not scientific conclusions—they are opinions grounded in my personal values. I’ll fight for them, but it would be dishonest for me to promote them while waving a “science-based” banner. Skeptics have a word for people who imply scientific authority for their non-scientific beliefs: “pseudoscientists.”

References

- Novella, Steven. “Skepticism and Religion—Again.” Neurologica. April 6, 2010. http://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/skepticism-and-religion-again/ (Accessed Aug 15, 2010)

- The accusation that the testable claims criterion is secretly intended to “coddle” religion is very common across the atheist blogosphere. For a specific response to Novella’s thoughts (cited above), see the (as of this writing) 230 comments following his post. For example, one commenter argued that the whole demarcation question arrises because “Skeptics are afraid to be seen criticising religion because religion is pervasive in the US,” to which Novella responded, “my position is NOT due to fear of pissing off the religious. It is a philosophical position that I have defended extensively. If you listen to the SGU and read this blog, it should be clear that I have no fears of pissing off huge segments of the population.” http://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/skepticism-and-religion-again/#comment-19298 (Accessed August 18, 2011)

- Swiss, Jamy Ian. “Overlapping Magisteria.” Speech delivered at The Amazing Meeting 2012. As posted on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIiznLE5Xno (Accessed August 31, 2012)

- Shermer, Michael. How We Believe. (New York: W.H. Freeman/Owl, 2003.) p. xiv

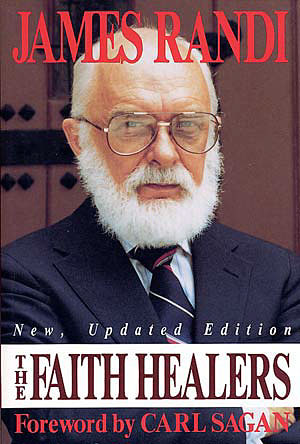

- Randi, James. The Faith Healers. (Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books, 1987.) p. 146

- Steiner, Robert. “Exposing the Faith-Healers.” Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 11, No. 1. (Fall 1986.) pp. 28–29

- Randi. (1987.) p. 146

- Shaw was also one of the “Alpha Kids” who, under Randi’s direction, misled parapsychologists into the belief that Shaw and colleague Michael Edwards had genuine psychic powers. See Randi, James. “The Project Alpha Experiment: Part 1. The First Two Years.” Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. VII, No. 4. Summer 1983. pp. 24–33 and Randi, James. “The Project Alpha Experiment: Part 2: Beyond the Laboratory.” Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. VIII, No. 1. Fall 1983. pp. 36–45

- Randi. (1987.) p. 147

- Randi. (1987.) pp. 147–148; Steiner. (1986.) p. 29

- Inside Edition. Feb 2007. As posted on Google Videos. http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-3999472423311387509 (Accessed September 10, 2011) [Link no longer current, but the video is easily found on YouTube.]

- Shermer, Michael. “God, ET, and the Supernatural.” Skepticblog. November 6, 2012. http://www.skepticblog.org/2012/11/06/why-there-cannot-be-a-deity/ (Accessed November 6, 2012)

- Novella. (2010)

- Novella, Steven and David Bloomberg. “Scientific Skepticism, CSICOP, and the Local Groups.” Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 23, No. 4. July/Aug 1999. pp. 44–46

Like Daniel Loxton’s work? Read more in the pages of Skeptic magazine. Subscribe today in print or digitally!

I think what bothers me about sticking to “testable claims” is not that it gives a pass to religious ideas, but that it privileges a very small segment of the skeptical community. JREF and the Independent Investigations Group may have the time and money to test claims, but most of us do nothing like that. In fact, the testing part isn’t even what I’m most enthusiastic about. For example, I love Skeptoid, but Skeptoid only does research, not testing. I like when Shermer talks about the psychology of beliefs, but that’s not about testing paranormal claims, it’s about scientific research that is relevant to skeptics. I love the discipline of critical thinking, but a lot of it is basically philosophy.

Sometimes I think you make a good case, but unfortunately the case you seem to be making is that I’m in the wrong movement. Surely this couldn’t be right, so could you comment?

Yes, I’m happy to comment. I think that the testable claims scope is often misunderstood to be narrower than traditional scientific skeptics have ever intended. It’s often asked, if the scope of skepticism is testable claims, why not just call this “science” and be done with it?

If I may quickly borrow from a comment I left on another post that asked just that question:

Most of my own work, for example is not science, but science-informed historical research. I am not a scientist. Nonetheless, I consider my practice to be bound to the investigable, and try to investigate as responsibly as possible: finding evidence, presenting it transparently, considering critical responses honestly and fairly, and so on. In short, an evidence-based practice grounded in the ethos of science.

Returning to your examples, Brian Dunning’s work on Skeptoid is similar in kind to my own work: empirical in scope, largely historical in practice. This type of work is and always has been central to the skeptical literature, as is the type of work practiced by detectives and investigative journalists. It necessarily has to be, because much of the work of skeptics deals with intentional fraud. Consider the observation with which psychologist and pioneering skeptic Joseph Jastrow opened his May 14, 1910 Collier’s Weekly article about an investigative sting of a then-famous spirit medium:

The subject matter of skepticism requires a multi-disciplinary approach. At the same time, it cannot be a field at all without some scope of practice. A field that is about everything is about nothing. Skepticism has long “restricted” itself to a not-remotely-restrictive scope: questions on which rigorous, verifiable evidence is possible at all—at least in principle. (The argument for further focus on paranormal and fringe science claims is another topic, but one I’ve addressed often—see this PDF, and also this one.)

So I think that you are in the right movement. I think you would be even if the testable claims scope were more narrow than it is. After all, science itself is by definition restricted to scientific boundaries, and yet I am not prevented from being an enthusiast and advocate for science by the fact that I am not a scientist.

If you are literally going out and testing claims (or doing historical research on such investigations), there is an obviously important dividing line between empirically testable claims, and merely philosophically questionable claims! But it doesn’t seem quite as important when if I’m a lay skeptic or if I’m just interested in the psychology of beliefs. The psychology of testable beliefs is about the same as for untestable ones.

Another way of putting it: It seemed like Jamy Ian Swiss was perfectly willing to argue about religion in his personal life, but not willing to take that stance as a skeptical activist. But as a lay skeptic, there isn’t much of a dividing line because everything I say is part of my personal life. Skepticism is just one interest that blends with my other interests.

In short, these boundaries are much more porous for lay people than for leaders and activists. It’s unsurprising to me that arguments over the scope of skepticism are occurring right when skepticism is expanding its popular base. I suppose I just want skeptical leaders to be aware of that.

I’m half-way through Why Is There a Skeptical Movement? and it’s great so far.

I’m glad you’re enjoying it.

You make a good point about lay skeptics. People should of course arrange and prioritize their personal lives in whatever way seems best. For myself, I am not especially interested in building a subculture of self-indentifying skeptics, but in skepticism as a field of research and activity pursued by professional, semi-professional, and expert-amatuer practitioners (and by serious volunteers and learners at other stages of development of their practice). It’s a distinction I discussed in a two-part post here and here.

The problem is the passivity in the face of the abscence of evidence. This leaves people powerless to most claims because most claims are made without evidence. I just don’t understand why is the “testability” demarcation so important while ignoring the a priori onus of evidence.

This also rubs off wrong actual scientists who if interested in a problem do not simply give up if a claim is considered untestable. Part of being a scientist is to make a model that predicts testable outcomes and this can be applied to any claim. This can be done to each one of the items in your laundry list. Don’t economists study the effects of taxation?

Until the skeptic leadership doesn’t accept the need to point out that faith based claims are false because there is no evidence to back them up they will be doing a disservice to its followers.

Jamie said “there’s no fucking god” to a bunch of atheists. He will also say it at TAM, I hope.

Yes, Swiss has a very public and very firm personal belief that god does not exist. I happen to have the same belief, and am happy to say so in any context, at TAM or anywhere else. What neither Swiss nor I nor any science-based skeptic will ever do under any circumstances is to present our personal beliefs regarding the existence of gods as though these were demonstrable, verifiable scientific facts. They aren’t.

It is a scientific fact that there is no evidence for any god. This is not a personal peefreference. There truly is no evidence and no reason to postulate its existence.

There is an assumption here that one should only believe in claims that are backed by evidence, this is an epistemic belief, not a scientific one, and completely in the realm of philosophy, not science. Some would even argue that such a belief is self defeating. Sorry, Daniel is right, this has nothing to do with science.

This is a common unnecessary philosophical complication.

On the contrary, it is a crucial epistemic consideration, and it is a shame that many scientists cant see the forrest from the trees and deem these non-scientific considerations unnecessary. Especially since the whole skeptical movement is driven by epistemic considerations.

Within the claim of “epistemic considerations” lies the implication that there is something else besides ontological naturalism. Everywhere we have looked or measured that has been nothing but the natural and material world. You are proposing an alternate epistemology in complete absence of evidence.

So are you, but here is your problem, you require that all claims be supported by evidence and you have not and cannot provide evidence for naturalism. Simply saying that all we observe is the natural world is not evidence for naturalism since naturalism requires evidence that the natural world is all there is and this, once again (we are seeing a trend here) is pseudoscience.

“cannot provide evidence for naturalism”

All of science is evidence for naturalism.

“All of science is evidence for naturalism”

This is an absurd statement, you clearly have some very significant limitations in your understanding.

Care to present your evidence for something else besides naturalism?

What exactly do you think Naturalism is?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaphysical_naturalism

I wish you would have put it in your own words because what you linked to and what you are claiming are completely different things.

Naturalism requires you to prove that nature is all that exists, saying all of science is evidence for naturalism makes no sense because science does not prove that nature is all there is. Do you get this?

Again. Please provide your evidence that nature is not all there is.

Your question is nonsensical, since naturalism is not a default position.

Just because you have no evidence for extraterrestrial intelligent life, does not mean that humanity is all there is. In order to say that humanity is all there is, you must prove that there is no extraterrestrial intelligent life.

Likewise, just because you have no evidence for the supernatural, does not mean that the natural is all that exists. In order to say that the natural realm is all that exists, you must prove that there is no supernatural realm.

Saying “all of science is evidence for naturalism” is extremely ignorant.

If you cant understand this, then we are wasting each other’s time.

Your examples are not appropriate because the existence of extraterrestrial intelligent life would be entirely compatible with the scientific observation that there is intelligent life in at least one planet. This is just an issue of detection and how common it is not an alternate reality.

To suggest that there phenomena entirely different or separate from the observable natural world is something entirely different and has no basis in reality.

“Part of being a scientist is to make a model that predicts testable outcomes and this can be applied to any claim. This can be done to each one of the items in your laundry list.”

That is itself an empirically testable claim. Can you please offer a model that predicts testable outcomes for any of the items on Daniel Loxton’s “laundry list”?

“Don’t economists study the effects of taxation?”

Yes, they absolutely do, and there are certainly many claims about taxation that are empirically testable (cutting taxes and government spending leads to economic growth, for example, or, conversely, deficit spending during a downtown spurs growth). But how exactly would you test the claim that “taxation is slavery”? That’s not a claim about the effects of taxation – that’s a value judgement about the morality of taxation. At least, I currently think that is the case. I may be wrong. Can you show me a model that predicts testable outcomes for this claim?

Yes. Asking you what you think.

Huh?

You can certainly empirically test whether I believe “taxation is slavery”, but how do you empirically test whether the claim itself is true? Maybe I’m entirely missing your point here (actually, I’m pretty sure either I’m missing your point or you’re missing mine), but would you please explain to me what your model for “taxation is slavery” is, and what testable outcomes it predicts? Or for any of Daniel Loxton’s “laundry list”, as you’ve claimed this can be done for any of them. I don’t think it can, but I may be wrong, and I’d be very interested to see a method of empirically testing the claim that “taxation is slavery” or that “Kirk is better than Picard” (although clearly, of course, he is).

There’s a big difference between what one personally believes and professes, and what one insists others must believe as well. “Testable claims” is such a broad concept that I really don’t think you will often come up against someone who does not actually make a testable claim. Who has actually argued for the Flying Spaghetti Monster, Russell’s teapot, Sagan’s invisible, intangible, heat-less, fire-breathing dragon, and the like? These claims are not testable because they are crafted to not provide any claim which can be examined, but when someone says “prayer heals,” they do not need to provide evidence to be said to have made a testable claim.

Besides, if they do manage to whittle away their claim to something which cannot be tested, then what do they even have left? They have an empty claim which they cannot reasonably expect anyone else to believe.

Such as the glib response(to the question of whether God answers all prayers) “Sometimes the answer is NO”.

Now I would call that an empty claim.

Most claims are *not* made without evidence. That’s part of the misunderstanding here.

For example as Sean Carrol puts it, this group of actual scientists/philosophers do not seem to have a problem addressing the god question:

“Due to the efforts of many smart people over the course of many years, scholars who are experts in the fundamental nature of reality have by a wide majority concluded that God does not exist. We have better explanations for how things work. The shift in perspective from theism to atheism is arguably the single most important bit of progress in fundamental ontology over the last five hundred years. And it matters to people … a lot

Or at least, it would matter, if we made it more widely known. It’s the one piece of scientific/philosophical knowledge that could really change people’s lives.”

http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2013/05/08/on-templeton/

The blog post you link to is actually tackling a different issue – the idea which the Templeton Foundation supposedly backs that science and religion are just two different paths to the same ultimate truth. Which doesn’t seem to be what Daniel Loxton is arguing for at all.

And “this group of actual scientists/philosophers” is actually a group of philosophy faculty members who participated in a survey. Which survey did not actually ask them whether they believed the existence of God is an empirically testable question, but merely what their position on the existence of God was, with only three reported categories of repsonses – atheism, theism, and other.

It seems to me that by defining oneself as a scientific skeptic you are simply placing an arbitrary and unhelpful limit on skeptical inquiry. A limit that that even self decribed scientific skeptics often ignore when it suits them. An example may be the dismantling of an argument by identifying logical fallacies within it.

Science is a powerful tool, but one of limited utility. Why accept that limit when logic and rational philosophy can be employed to great affect?

I agree with you in that science has limited utility, however think this is where the pragmatism of skepticism comes into place.

One way to demarcate science from philosophy (by no means the only way, and it is not a firm solution to the demarcation problem) is on grounds of practicality. Science emerged when natural philosophy produced tools that were so precise, the predicted outcomes could be invested in by authorities. Empiricism is a clear revelation of this predictive power.

Skepticism developed as a means of asking just how useful the predictions made by particular sub-cultures are. It is intrinsically based on decision making surrounding specific claims, and not merely the holding of a belief.

That’s why atheism is not an inevitable outcome of scepticism. Only when a belief manifests into a prediction or claim can scepticism be of use.

I feel scientific scepticism is something of a tautology – there is no such thing as non-scientific scepticism. If anything, scepticism is historically interested in addressing predictions and claims that are made with confidence through non-scientific means, and is therefore merely a focussed subset of scientific inquiry.

“That’s why atheism is not an inevitable outcome of scepticism.”

Yes it is once it is understood that evidence is required for claims and that faith claims without evidence are indistinguishable from fantasy.

This is ridiculous, faith, by defenition is belief without evidence. Belief with evidence is not faith. You keep throwing out pseudoscientific self defeating claims and are trying to pass them as scientific.

Please show me evidence that “evidence is required for claims”…

Think about it. If you have to believe it, it is probably not true.

Indistinguishable from fantasy is not the same as demonstrated false. Scientific evidence is only useful once a belief makes a prediction.

Many non-predictive, non-scientific beliefs (such as deism, or Last Thursdayism) are simply non-parsimonious. Given parsimony is a useful scientific tool, and not a provable law, the ‘truthfulness’ of such ideas is scientifically irrelevant.

One can claim any old thing about the universe, and believe it true. Culturally and personally, this might be useful for comfort or social cohesion. For anything else, it’s neither here nor there.

Once it takes on predictive qualities science can be applied to determine the likelihood of that outcome. Until then, opposing it is little more than bigotry – a pure discomfort at the idea that somebody might not share your worldview.

Not all predictions and claims are made within a scientific framework. God will answer my prayer with a yes, a no, or a maybe later. This is both a prediction, a claim and a load of bollocks. It is not addressable by science, however is it addressable logically and philosophically.

As a specific claim this statement regarding prayer forms part of a wider belief system which involves many claims and predictions. Some addressable by scientific methods, others not. I would reiterate that that while a scientific skeptic may say that only the scientifically testable claims are with their purview, this in my view is arbitrary, limiting, and unnecessary.

Scientific skeptisism may not predict atheism, but a wider skeptical outlook probably does.

I would argue that Popoff’s audience buy into the non scientific claims, that God exists, and use that belief to ignore evidence against testable claims. In other words exposing Popoff addressed a symptom rather than the cause.

Andrew,I think your last statement got it exactly right (if I fully understood it). You cannot reason a person out of a position that they did not reason themself in to.

If that is “the cause”,then I think that we are defenseless trying to use facts and logic to persuade those who are use to dealing with gut feelings,tradition,and folk tales to decide the “truth” or “fiction” in a reality of their own construct.

I’m not sure I’d agree that it is a prediction, though the term might need better defining.

I can also say ‘God will change the universe in a way that nobody can detect’. Because I’ve said ‘will’ and included a verb, the statement looks like a prediction in terms of syntax. But nothing can be observed, so are we really using prediction in the same way?

It is illogical, absolutely. And it has zero predictive power. It’s as harmless as it is useless.

Its ironic that you use Michael Shermer’s words to support your thesis (which I agree with 100%) when Shermer’s last few posts on here have been about how science can determine morality. Talk about pseudoscience.

Harris and Shermer do not say that science can determine morality. This is a mischaracterization. They say science must be used to establish facts that will allow us to argue what is the most moral outcome. Very important distinction.

And the most moral outcome is thst which maximizes human flourishing, this, is not a scientific conclusion, it is purely a philosophical one. You cant scientifically conclude that we should value human flourishing above all else, say personal flourishing or pleasure. Their whole premise relies on a subjective non scientific axiom and to say that science can determine human values ( Harris’ subtitle) is pseudoscience.

“You cant scientifically conclude that we should value human flourishing above all else”

And no one ha said this is the cause. You only have to prefer human flourishing because you are a good moral human being. Do you agree with those that would oppose human flourishing?

This is circular, if my moral values should strive to maximize human flourishing, it is circular to claim that I have to prefer human flourishing because I am a moral person.

It is not circular because it originates within you as a moral person. Morality is a preference.

Well, I share Michael’s view that science can very usefully inform our decision-making and even inform our moral intuitions. I also share his 1997 view, expressed in conversation with Martin Gardner, that, “Some of these ethical issues seem irresolvable on a natural basis. Like abortion. How do you come down one side or the other using science or reason, without calling on something higher, like ‘rights,’ which is itself a metaphysical concept?” (Shermer, Michael. “The Annotated Gardner: An Interview with Martin Gardner—Founder of the Modern Skeptical Movement.” Skeptic. Vol. 5, No. 2. 1997. p. 58.)

On the other hand, I do not think that his suggestion that “The Is-Ought problem (sometimes rendered as the ‘naturalistic fallacy’) is itself a fallacy” is correct. He is aware that our views diverge on this issue—it’s a point of disagreement that I have expressed to him here in public at Skepticblog, and also touched upon in private communication. That’s not to say that his moral intuitions and philosophical arguments in favor of prioritizing “human flourishing” do not have much to recommend them. Human flourishing sounds like a pretty good goal to me. Still, appealing as those arguments may be, they are at the core philosophical arguments grounded in personal moral values, in my opinion.

It’s true that skeptical methods can’t disprove a faith-based, untestable claim. But that doesn’t make it reasonable for a skeptic to make such claims herself. Skeptics reach conclusions based on reason and hypothesis testing, not on faith. So if a theist and an astrologer both claim to be skeptics, and the theist’s claim is blithely accepted while the astrologer’s is met with derision, then that’s a religious exemption.

This is only true if your unstated major premis is that skeptical methods are limited to scientific methodology. If you use logic and reason you can happily refute untestable claims all day long.

I’d encourage readers not to get too hung up on “skeptic” as a label, nor as a portfolio of beliefs. The point of scientific skepticism is to see what light can be shed upon paranormal and fringe science claims using the tools of science and rigorous scholarship. There are many people who have made important contributions to the skeptical literature who held religious beliefs; likewise, many valuable contributors to the skeptical literature have held highly dubious beliefs about politics, society, science (think of the many prominent skeptics who have attempted to refute or debunk climate science), or even the paranormal. People are inconsistent, but what of it? It’s useful work we want, not a litmus test for a subcultural identity.

In the example you give, one would hope (but not assume) that the astrologer would be well-grounded in the skeptical literature on astrology, that the theist would distinguish between her faith claims and her scientific claims, and that both would be prepared to defend any testable claims they might make in support of their personal beliefs. But even if none of that is the case, I hope they’ll both find something in the skeptical literature that is useful to them.

How are the faith claims of the theist different from the claims of the astrologer?

They may be different, or they may not—it depends on the case. Often, astrologers have asserted that astrological effects can be demonstrated and measured, while theists typically do not. If our hypothetical astrologer instead asserts some sort of undetectable metaphysical effects of astrology, then it is just another untestable faith claim. If the theist asserts some sort of measurable effect of her deity, that is just another testable claim.

I’ll answer a lot more concisely. No evidence for either.

Somite – That is not concise not does it add to the discussion. You have stated your beliefs but have failed to back them up repeatedly. You have yet to affirm the consequent.

How do you view the claims of scientists like Richard Dawkins, Victor Stenger, Sean Carroll and others who think (and write) that the God question is within the purview of science?

Also Lawrence Krauss, Jerry Coyne, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, Larry Kroto, Stephen Hawking, Isaac Asimov, Carl Sagan, Arthur C. Clarke, Douglas Adams (OK, no a scientist but C’mon), PZ Myers, probably Proffessor Brian Cox, I know I am leaving out some..

Ah! I forgot Stephen Weinberg..couldn’t leave him out.

That’s right. It seems like the science these scientists offer is a much more useful and widely applicable tool than the skepticism the Skeptics Society offer.

What really get feathers ruffling is that the writers of the Skeptics Society insist on claiming that science can’t address the God question, or even religion more generally (“science as a whole has nothing to say about religion” in Loxton’s words). That’s a controversial claim to put it mildly. If the Skeptics Society had put something along the lines that “We are not interested in examining arguments for or against the existence of God, but in examining whether paranormal claims are real, which is our area of focus” then there would be much less heat surrounding this question. As long as they insist on maintaining a very controversial position as established fact, heat will persist.

Surprisingly Brian Greene agrees with the testable point of view

http://www.newstatesman.com/blogs/helen-lewis-hasteley/2011/06/physics-theory-ideas-universe

Interestingly he gets Templeton money. Is that what you are after?

I’ve heard Dawkins say that the existence of god “may be” a testable claim. If so, great. I’m not terribly familiar with Stenger’s work, apart from my sense that he thinks the universe looks like it does not require any sort of god. I agree with that. The traditional scientific answer is that of scientific skepticism: “I have no need of that hypothesis.”

Dawkins is very explicit in The God Delusion that the existence of God is a scientific hypothesis:

“Perhaps you feel that agnosticism is a reasonable position, but that atheism is just as dogmatic as religious belief? If so, I hope Chapter 2 will change your mind, by persuading you that ‘the God Hypothesis’ is a scientific hypothesis about the universe, which should be analysed as sceptically as any other.” – Page 2

“Contrary to Huxley, I shall suggest that the existence of God is a scientific hypothesis like any other. … God’s existence or non-existence is a scientific fact about the universe, discoverable in principle if not in practice. … And even if God’s existence is never proved or disproved with certainty one way or the other, available evidence and reasoning may yield an estimate of probability far from 50 per cent.” – Page 50

Stenger has a book written called “God: The Failed Hypothesis: How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist”.

Sean Carroll (theoretical physicist) has also written extensively on the topic. For example “Why (Almost All) Cosmologists are Atheists” ( http://preposterousuniverse.com/writings/nd-paper/ ) and “Does the Universe Need God?” ( http://preposterousuniverse.com/writings/dtung/ ) and the blogpost “Science and Religion are Not Compatible” ( http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/cosmicvariance/2009/06/23/science-and-religion-are-not-compatible/ ).

Again, it would result in much less heat to declare that atheism/religion in not wiyhin your focus or interest, rather than insisting on a controversial position that plenty of scientists apparently don’t agree with.

I’m not about to accept the controversial positions of handful of atheist activists as representative of the wider view of scientists. (These are, you realize, positions novel enough to them that they felt they were good hooks for controversial books?) But regardless, many skeptics have argued just as you ask: that for reasons of division of labour, skeptics will stick to the testable paranormal claims that we do best. Paul Kurtz, for example, argued in 1999 that,

Atheist hardliners are no more willing to accept that pragmatic argument than any other. The only answer that will satisfy atheist activists, apparently, is that skeptics must accept that atheist activism is the most important cause in town.

That’s an impasse that skeptics resolve by getting back to our own work.

I imagine that it goes right over your head that what you are saying here is that the atheism is not a skeptical position.

“Atheist hardliners are no more willing to accept that pragmatic argument than any other. The only answer that will satisfy atheist activists, apparently, is that skeptics must accept that atheist activism is the most important cause in town.”

This is not true. I think what is jarring to atheists is the unwillingness of the new skeptics to simply state there is no evidence to the God hypothesis. Paul Kurtz position is a lot more honest than the philosophical “testable claims” position. Paul is just saying “we just don’t want to” which is a perfectly acceptable reason.

“These are, you realize, positions novel enough to them that they felt they were good hooks for controversial books?”

I don’t see what that’s supposed to mean. Books are still written to defend evolution, more than a century after it was widely accepted by the scientific community.

“But regardless, many skeptics have argued just as you ask: that for reasons of division of labour, skeptics will stick to the testable paranormal claims that we do best.”

Sure. The heat arises when the same skeptics insist on a controversial position (that science has nothing to say about God and/or religion) rather than saying that they are not interested in that subject.

If skeptics simply stated their disinterest in God/religion instead of taking stances on what science can and cannot do, much less controversy would result.

To be clear, skeptics have said both for decades—that the “testable claims” distinction is meaningful and important, and also that we have a useful area of niche speciality that deals with empirical paranormal and fringe science claims. The philosophical distinction between claims that can be investigated and claim-like utterances that cannot be investigated is the most important reason for scientific skeptics to maintain clarity on our “testable claims” mandate, but there are a perfect storm of additional, converging practical reasons to do so as well. Pick any reason you happen to find congenial, but the historical fact is that scientific skeptics and other parallel rationalist movements have always broken naturally along those lines. My expectation is that roughly the same natural breaking lines will always re-emerge as a result of the diverging interests of the people involved, no matter what you or I say about it.

I’m not entirely certain that you’re serious on this point, as “taking stances on what science can and cannot do” is what skeptics do. That’s why this blog exists. It is, for example, the role that skeptics have played in combatting intrusions of “scientific creationism” and Intelligent Design into science classrooms—explaining to the courts and the public that ideas about gods and miracles are outside of science by definition, no matter how much creationists wish to position any of these as “just another valid scientific hypothesis.”

As well, many skeptics in fact are very interested in god or religion. Insofar as religions make testable claims, scientific skeptics are typically eager to tackle them. Indeed, some skeptics (such as Eugenie Scott or Joe Nickell) have specialized in engaging with claims of that type. But many skeptics are also personally interested in the untestable claims of religion (whether for, against, or what have you). We just explore those ideas outside the framework of the organized project of scientific skepticism.

All the views that you have quoted point to the extremely unsophisticated philosophical thinking that litters popular atheism. It is predicated on the very ironic and ignorant claim that belief in god is simply about natural explanation and that this is the reason why theism even exists.

This is a terrible misrepresentation, a strawman if you will, in order to bring belief in god completely within the realm of science and refute it against more plausible scientific hypotheses.

This ignorant line of argumentation is not only very disappointing, as an atheist, it is also an extension of what many in the skeptic community defend. Many of the most important beliefs that we hold are unscientific in nature and cannot be tested through any kind of scientific inquiry. I say that these things are the most important because science itself is permeated with beliefs and axioms that cannot be scientifically proven. These are basic philosophical limitations that unfortunately, renown scientists chose to ignore.

To say that nothing is out of the scope of scientific inquiry, including the existence of god, makes me really question the objectivity that we skeptics claim to be driven by.

Please provide evidence that there is something beyond the scope of scientific inquiry.

Thats a non sequitor, if there is evidence for something beyond the scope of scientific inquiry, then it is not beyond the scope of scientific inquiry.

I would suggest that you read “What Questions Can Science Answer?” by Sean Carroll: http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2009/07/15/what-questions-can-science-answer/

Very well written, and might shed some light on your concerns.

And no, science can’t answer all questions. It can’t answer questions of morality (but it can inform them). This does not mean that religion can though.

NOMA fails because religion not only make moral statements, but also statements of fact. Jews, Christians and Muslims will disagree with you if you say that the exodus from Egypt is a mythological story that never happened (which is what history and archeology tell us).

Some philosophers point to the anthropic principle as evidence of design. You could counter with parallel universes, but how testable is that?

“explaining to the courts and the public that ideas about gods and miracles are outside of science by definition”

They are not outside of science. Science is very clear about gods and miracles. There exists no evidence for either of them everywhere we have looked. The Higgs field and particle show that there is no room for anything else in the fabric of the universe.

Gods and miracles are outside of science only in the sense that they are imaginary.

Does string theory fit into this discussion at all? (I am especially interested in Somite’s thoughts).

My knowledge of string theory is limited to what I can understand in programs on Nova and the Science Channel, so my assumptions may be completely off base (in which case, please let me know). That said, my understanding is that string theory is currently, and might forever be untestable, and may ultimately remain a set of esoteric formulas. Some physicists I recall, have basically argued this point, and have denigrated string theory as “not even wrong”.

IF this is correct, is string theory, at bottom, the same thing as the claim that god exists, perhaps in the way that a deist might believe? That is, string theorists appear to arrive at their conclusion based on logic and reason alone. In the same way though, a deist could reason, albeit in a much more simple way, that there was, roughly speaking, a “Big Banger”.

So, from people who make up the skepticism = atheism camp, what do you believe the “correct” skeptical view of string theory is.

Curious what people that appear to be a lot smarter than I am might think.

String theory is a hypothesis and as soon as someone starts trying to pass laws restricting rights because string theory says so I will point out that they have no evidence for their beliefs and then laugh at them.

Hi Daniel. Mathematical models do not necessarily reflect reality. They are of interest to mathematicians because they can be derived from mathematical rules. Some are hypothesized to reflect reality in which case they must match experimental observations or predictions.

String theory is a correct mathematical theory that has been hypothesized to describe reality and it has made some predictions that have yet to be tested.

The difference between mathematical models and the paranormal or the god hypothesis is that the latter two are not models and have not even a mathematical basis and yet are predictions of the nature of reality.

Being that biblical scholars have argued for centuries about what the Christian bible(s) say or mean,I am not sure how you could ever pin down any claim that the bible makes that someone couldn’t move the goal posts on by claiming a mistranslation,metaphor,etc.

Robert Price’s “The Human Bible” podcast has a segment called “Apologetics Is Never Having To Say You’re Sorry” that pointedly demonstrates that believers (highly educated ones at that)will use the bible as what Price calls a “ventriloquist dummy” to get it to say whatever they want it too.

So,how do you put such a system to a test,when they have an infinite amount of ‘get out of jail free’ cards to play?

Skeptics traditionally don’t bother with the whole vague system. If someone wants our attention, they can propose something less vague. When big vague claims can be broken down into concrete components, we’ll happily look at those…to the extent that skeptics qua skeptics are qualified to do so. For discussion of the danger of skeptics blundering as unqualified amateurs into other people’s areas of domain expertise, see “Why Is There a Skeptical Movement?” (PDF), pp. 42–46 (“Skeptics are Not Everythingologists”).

Stephanie Zvan has a response to this post up: http://freethoughtblogs.com/almostdiamonds/2013/05/08/skepticism-religion-and-strawmen/

Her basic point, as I understand it, is that the “testable claims” exclusion is unequally applied to some topics, like religion, while not applied to others, like homeopathy, even though there are false testable claims (and untestable claims) made by both.

I (and I suspect others) would be curious about your response, if any.

My guess is that there are an unequal number of testable claims between something like homeopathy and all of the religions that I’m aware of. I suppose a biblical literalist will candidly admit that humans cannot and never will be able to reproduce the burning bush or explain it by the scientific method. If that’s what you’re asserting, there’s really nothing to test, even in theory.

Or maybe, when it comes to what skeptics ought to be interested in examining, the answer is “I know it when I see it”.

Stephanie’s argument – as usual – is all over the place.

In her personal experience, she’s never come across deists who describe non-interventionist gods. Fine. An argument from ignorance, but so be it. I’ve come across plenty, but really it’s irrelevant. The argument is about claims which cannot be tested and its relevance to skepticism.

She also misses the point with homeopathy. Even prominent skeptics like Randi claim if it can be shown, show it. No, vitalism as a nebulous, non-empirical hypothesis can’t be tested. In fact, the history of vitalism is a lot more convoluted and wrapped up in the nature of materialism than Zvan alludes to. It’s not a simple thing to define, which is why it’s ignored as vague and useless.

Yet historically, every time a vitalistic quality has been described in empirical, testable terms (and there have been plenty), it has become a materialistic theory in biology. Many things, from endocrinology to neurology, has had origins in vitalistic theories which evolved into testable concepts.

Can physics answer why there’s something instead of nothing? Is that testable?

I just read Lawrence Krauss’s latest book Why There is Something Rather Than Nothing. What I got from it is that it depends on what you mean by “nothing.”

He’s gotten some push-back from some philosophers.

Unfortunately, there is a trend in the popular science community where the more accomplished a popular scientist becomes, the more idiotic and retarded a philosopher they turned into. Lawrence Krauss is yet another example of this.

I don’t see science or philosophy or faith here. I see tribal politics. The atheists want to fold the skeptics into their tribe, to join their war with the God-worshipper tribe. If they can convince enough others to join them, they can take the God-worshipper tribe’s food and women.

By concentrating on their own fight against the paranormal fraud tribe, the skeptic tribe aren’t helping the atheist tribe. This makes the atheist tribe angry, because they hate the God-worshipper tribe much more than the paranormal fraud tribe. So now they’re threatening the skeptic tribe. Maybe the atheists will take the skeptic tribe’s food and women instead.

Reply to http://www.skepticblog.org/2013/05/08/testable-claims-is-not-a-religious-exemption/#comment-84871 by Daniel Loxton:

“Pick any reason you happen to find congenial, but the historical fact is that scientific skeptics and other parallel rationalist movements have always broken naturally along those lines. My expectation is that roughly the same natural breaking lines will always re-emerge as a result of the diverging interests of the people involved, no matter what you or I say about it.”

I’m curious where you would put the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science in your taxonomy. It does not contain “atheism” in its name or in its mission statement ( http://www.richarddawkins.net/home/about ). It clearly bills itself as a pro-science organization, yet it seems not to fit in with the self-identified scientific skeptics.

“I’m not entirely certain that you’re serious on this point, as “taking stances on what science can and cannot do” is what skeptics do.”

Didn’t you just write that skeptics investigate paranormal claims?

And it seems something is seriously out of place if the skeptics’ view of what science can and cannot do is not in agreement with the views of many scientists.

I’m not able to comment with any authority about the Richard Dawkins Foundation, but my impression as a casual outside observer is that they are first and foremost an atheist activism organization. Their projects page seems to support that interpretation. Their resources page specifies, for example, “We have assembled a superlative team to lead secularism and atheism into the future. The Richard Dawkins Foundation, US has unparalleled resources to achieve that mission.”

Scientific skepticism’s understanding that claims that are not in any empirical sense “testable” or investigable using empirical tools are therefore outside of science is a run-of-the-mill, mainstream view within the scientific community. See for example, the position of the National Academy of Sciences that “Science is…a way of knowing that differs from other ways in its dependence on empirical evidence and testable explanations.… Because they are not a part of nature, supernatural entities cannot be investigated by science.”

Also the NCSE and they have both been soundly criticized by the list of scientists above.

“Their resources page specifies, for example, “We have assembled a superlative team to lead secularism and atheism into the future. The Richard Dawkins Foundation, US has unparalleled resources to achieve that mission.””

Okay, but what of, say, their donations to Oklahomans for Excellences in Science Education? Of Dawkins’ books, only one deals with religion explicitly, the others are about science, though many of them to touch on religion (which is unavoidable).

Michael Shermer has taken part in several debates about religion, saying numerous times that science shows that religions are made up. It’s even at the frontpage of skeptic.com. Yet to refer to Shermer as an atheist activist would be narrow-minded.

“Scientific skepticism’s understanding that claims that are not in any empirical sense “testable” or investigable using empirical tools are therefore outside of science is a run-of-the-mill, mainstream view within the scientific community.”

The view of religion you have seems to be that it’s about a being that exists outside of the universe and doesn’t do and never did anything, and that’s it. Yet that’s not what your average believer believes. Religious books are full of historical and scientific claims.

Is the story of the exodus in the Bible (and Quran) true? Does prayer improve chances of recovering from disease? These claims have been tested, and in both cases religion ended up with the short stick.

“See for example, the position of the National Academy of Sciences that “Science is…a way of knowing that differs from other ways in its dependence on empirical evidence and testable explanations.… Because they are not a part of nature, supernatural entities cannot be investigated by science.””

As you probably know, the aforementioned scientists disagree. Heck there are even academic studies on the relationship between science and religion.

What should really be said is that scientists disagree on the issue, rather than a blanket statement that science has nothing to say about religion (not true, as demonstrated above).

The very fact that in the US so many scientists are atheists compared to the general population should tell us something. I doubt that the religiousity of, say, bakers or accountants differ in significant ways from the population as a whole. The two possibilities I can see are that either science is corrosive to religious beliefs or atheists are more likely to be into science in the first place.

You didn’t ask about Richard Dawkins the person. His personal contributions to science and the promotion of science literacy are obvious. Nor did I deny that his foundation is friendly to science. Of course it is. Nonetheless, my impression is that it is most accurate to describe the central concerns of the RDF as focused upon atheism, secularism, and religion.

Michael and I are both atheists personally, and the Skeptics Society that we represent professionally is neighborly toward parallel rationalist movements. Nonetheless, Michael’s position on the testability of god is not dissimilar to my own. For example, see his quote in the post above. For much of his career in skepticism, Michael described himself as an agnostic specifically to underline the fact that science is not able to resolve untestable faith claims.

Yes, and to the extent that it is is possible to shed light upon those claims using evidence, all of them are in scope for scientific skepticism—at least in principle. That is the theme of the article above. (Whether we are in practical terms qualified to contribute to the scholarship on those questions is another matter.) The empirical scope of skepticism seems to strike some people as restrictive, but that sentiment seems utterly bizarre to me. “Testable claims” is almost synonymous with “answerable questions” or “knowable facts”—essentially the whole of the scope and literature of every branch of experimental and observational science and social science, historical scholarship, journalism and law enforcement combined. This is not too narrow, but impractically broad.

Well Dawkins has stated in interviews that he doesn’t view his advocacy for science and his advocacy for atheism as separate, but that they belong together. But of course one can disagree with that.

The introduction video to his foundation ( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OAcFseob0oA ) doesn’t even mention atheism.

Again, it seems the disagreement is exactly about how broad the scope of scientific investigation is. It also seems unlikely that it’s going to be resolved here. But I’d like to ask, is your position that if something is (in principle) answerable by science, it is within the scope of scientific skepticism?

Yes. Expressing that position was the intention of this post. If I may quote the piece above:

Note that this ridiculously broad scope is so vast as to be almost meaningless. In principle, all topics are in scope if evidence is possible even in principle; as a practical matter, additional factors constrain the topics that skeptics qua skeptics can tackle responsibly or well, such as knowing what we are talking about.

Just read in the New Yorker

“To emphasize the qualitative conclusion (X has not been absolutely proven to be false) while ignoring the collective weight of the quantitative data (i.e., that most evidence points away from X) is a fallacy, akin to holding out a belief in flying reindeer on the grounds that there could yet be sleighs that we have not yet seen.”

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/elements/2013/04/schmidhuber-eagleman-science-religion-artificial-intelligence.html?mbid=social_retweet?mobify=0&intcid=full-site-mobile&mobify=0

This says absolutely nothing new since there is no such thing as “absolutely proving something”, everything that we prove is of the “most evidence points to X” variety. On top of that, even if you could definetly prove something, that proof is predicated on other assumptions that are not absolutely proven.

It seems to me that religious experience may not be verifiable but there is a class of experience that comes close on the continuum of experience and is verifiable. Aesthetic experience can be tested and I suspect that there will occasionally be cases where measurable experience cannot be attributed to determinism. If this is the case and even one such instance can be established, then there will be proof that ALL experience is not deterministic. I believe William James posited something of this nature in his writings (atheists likely fear the answer). Personally, my belief is that it is already settled. If I were a brilliant scientist and not an average artist – this is what I’d be testing. For now I’m content to create things.

Given that this article is at least in part a reply to Myers’ (very justified) rant I think it’s extremely cowardly not to mention him, and a feat of great intellectual dishonesty not to take on his (easily justifiable) reasons and views.

You disappoint.

To be clear, this was written almost two years ago, and published last February. I haven’t read the piece you refer to.

>>“If someone says she believes in God based on faith,” clarified Michael Shermer, “then we do not have much to say about it. …”

I would hate to fall for the argument from ignorance and conclude that a claim is untestable merely because I couldn’t think of how to test it.

What does a constructive proof that something is untestable look like?

What is a “constructive proof” outside of mathematics?

Just because there is no way to test it doesn’t mean it’s true. People are building strawmen out of a very straight-forward, concise blog post. I think the anti-theist emotions have clouded so many wanna-be skeptics thinking. Richard Dawkins is a scientist and an atheist. He doesn’t promote skepticism, per se. There is a difference that zealous atheists don’t want to accept the definition of scientific skepticism no matter how clearly it’s explained to them.

If religious guys are right that the real methods of getting to know the truth are revelation, talking the gods, participating in miracles etc. then this whole enterprise of skepticism is quite worthless, as it’s based on the investigation of reality, using methods derived from reality. Reality being only a tiny, non-important part of the bigger whole according to theists with their eternal paradises, and gods transcending and even controllig it.

So if a skeptic cares about what the VALUE of skepticism is, then he must make a decision on ideologies of religions. Skepticism is only of high-value if these are false.