What Was in Patent Medicines

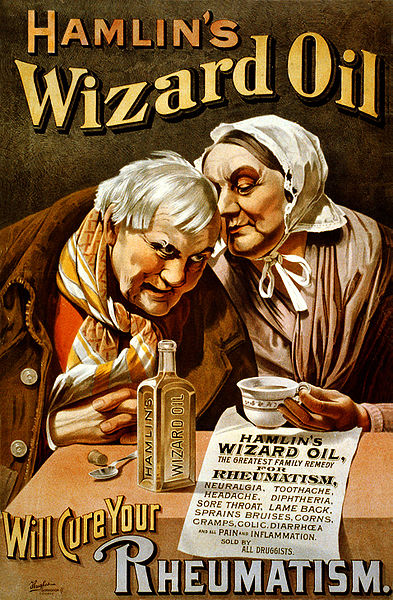

What was actually in Thompson’s Cattle Powder, Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, or Hamlin’s Wizard Oil?

What was actually in Thompson’s Cattle Powder, Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, or Hamlin’s Wizard Oil?

Prior to regulation by the FDA, over-the-counter medicine in this country was largely a creation of small businesses. There was a large variety of so-called “patent medicine,” each a proprietary blend of – what?

The term “patent medicine” has nothing to do with being issued a patent. The term refers to a letters patent, which is essentially permission to use a royal endorsement. Most patent medicines were not actually patented mainly because the promoters did not want to disclose their ingredients.

Instead, such products were branded and their brand heavily marketed.

As a result the ingredients of these patent medicine products were largely unknown. Compounding pharmacists were familiar with the ingredients, however, and often sold cheap knockoffs, making it all the more important for promoters to protect and promote their brand.

A study presented recently at a meeting of the American Chemical Society reports the analysis of 50 different patent medicine from a collection in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn Mich. The results will probably not surprise you:

“Many patent medicines had dangerous ingredients, not just potentially toxic substances like arsenic, mercury and lead, but cocaine, heroin and high concentrations of alcohol.”

The heavy metals were likely largely contaminants, but sometimes they may have been deliberate. Mercury and arsenic, for example, were used at the time as treatments for syphilis. The other common ingredients were often the true active ingredients. Heroin is a narcotic and would have been effective at treating pain. Cocaine is an addictive substance – which makes it good for repeat business. And alcohol is could certainly take the edge off of many complaints, at least in the short term.

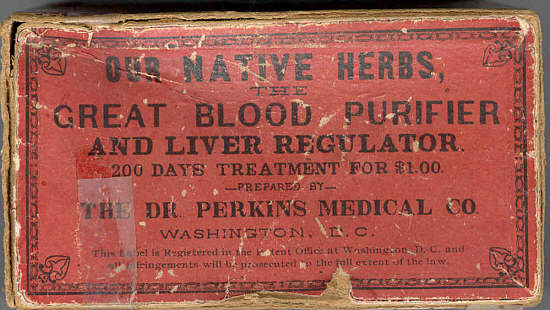

Ingredients were largely not advertised, although sometimes a main ingredient like heroin was part of the promotion. Often the implication given was that a special blend of natural herbs were the main ingredients, but that was just for show.

None of these products were the result of careful research. The manufacturers had no need for such expenses. They were motivated to make grandiose claims, promote their brands, to include cheap ingredients, and to include an ingredient that would give a good “kick” to their customers so that they would feel it was working.

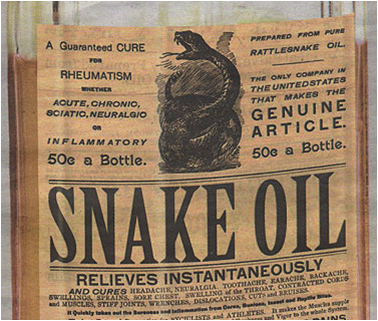

While we may look back at such products as quaint and hokey, there is essentially no difference between them and the supplements that are all the rage today. After the 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act that essentially removed supplements from FDA regulation, we have had a return of the patent medicine era.

Today you can find countless products, heavily branded and marketed, with grandiose claims, often cut with something like caffeine or another legal stimulant to give a nice kick, and marketed without the need to provide any evidence for safety or efficacy.

There are two main differences, however. The first is that the ingredients need to be disclosed. The second is that promoters cannot claim to cure diseases, but have to restrict their claims to “structure function” claims. This is a massive loophole, however, as they can make claims that their product supports some biological function with the clear implication of what it is treating.

There are two main differences, however. The first is that the ingredients need to be disclosed. The second is that promoters cannot claim to cure diseases, but have to restrict their claims to “structure function” claims. This is a massive loophole, however, as they can make claims that their product supports some biological function with the clear implication of what it is treating.

Airborne is a great example. This is heavily brand marketed, with the notion that it was created by a school teacher, as if that is a credible source for a medicine. The claim is that it will support your immune system, so take it before you get on a plane to prevent contracting a cold or other infection from all the close contact. In reality it’s just a mixture of vitamins and minerals, and there is no reason to think that it will support the immune system to prevent colds.

Today anyone can combine a random mixture of cheap ingredients – herbs, vitamins, or minerals – and then imply whatever health claims they wish for their mixture as long as they are slightly careful in how they word the claims.

This is a simple result of market forces in the absence of effective regulation. There is no reason to think that the snake oil herbs and supplements of today would be any different from that patent medicines of previous centuries.

s/alcohol is could/alcohol could/

The first response reads much like a deceptive label. Good work.

In my local drug stores, the medicine that doesn’t work costs as much as the medicine that does.

Information regarding the components of many of the patent medicines of the early 20th century can be found in the AMA publication Nostrums & Quackery which is available at archive.org and other sources.

Regarding the components of modern products, let me cite my own experiences from a period as consultant to the US Postal Inspection Service during the 1980s. Many products were marketed as herbal remedies, and had enough information about their formulation to be evaluated based on standard texts such at the United States Dispensatory 1980 edition and Martindale’s Extra Pharmacopoeia. These products commonly contained herbs or herbal extracts that had formerly been used in conventional medicine, however they were provided in significant underdoses. Before the development of high potency tinctures and extracts, medicinal doses were in terms of teacupful, ounces, and grams. Common use of medications that could be measured in milligrams did not appear until the mid-20th century, yet these products would commonly contain 100 – 250 milligram quantities of the herbs themselves. As a result, they were non-toxic, but valueless, and delayed the patient from obtaining effective treatment.

Products such as Airborn are commonly marketed as homeopathic remedies, which could be subject to extended discussion. Those interested should see http://www.fda.gov/ICECI/ComplianceManuals/CompliancePolicyGuidanceManual/ucm074360.htm

I might note that heroin, although a major drug of abuse, was widely used as a cough suppressant, as was codeine. Both were mixed with elixir terpin hydrate, itself of little value but containing 39 -44% alcohol. Elixir terpin hydrate with codeine was formerly available as an over-the-counter preparation and was widely abused. Even after heroin was banned in the United States, elixir terpin hydrate with heroin was available as a cough remedy in Europe.

May I also recommend James Harvey Young’s fascinating book on the subject of early quackery The Toadstool Millionaires, which is available on-line at Quackwatch.org

Great commentary!

I raised my children mostly in Washington State in the 70’s and 80’s and while I’m pretty sure this has now changed, I used to be able to go to the drugstore, sign my name in a big, important looking book as the white-coated pharmacist looked on very authoritatively, and then I could buy a smallish bottle of cough syrup with codeine. I have no idea how much codeine was in it, but it stopped the kids coughing all night long and keeping my awake as well. Once they could sleep, it was amazing how much faster they seemed to get better. I never gave them any other meds for colds unless the doc specifically directed something (but I did dole out lots of homemade soup and TLC).

I notice that these days there is a huge selection of cold/flu “medicine” for children and I find it alarming–mostly that people think they have to intervene at all in the average cold.

As for me, I find a hot toddy (generous on the toddy) helps a cold at least SEEM to get better. :-)