Talking ’bout my generation

Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans

—John Lennon

Forty years. In some contexts, it’s not very long, but in the span of a human lifetime, it’s huge. Only a few generations ago, most humans did not live past their 40th year, and in some parts of the developing world, they still don’t. However, in the Western World, most of us can not only assume that we’ll live at least 40 years, but many of us will survive for 80 years or more. Still, 40 years is a long span of time, when most people can assume that life will have changed in many ways and thrown a lot of surprises at them.

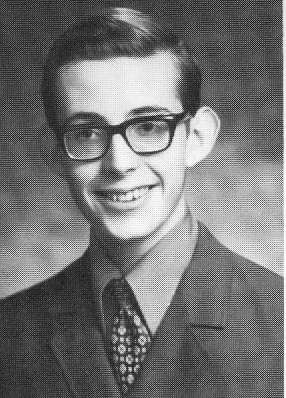

Last weekend, my high school class (Glendale, California, High School Class of ’72) had their 40th reunion. It was a real eye-opener for me. I missed the 5th year reunion in 1977 because I was in grad school at Columbia University in New York, and the tenth reunion because I was in my first teaching job at Knox College in central Illinois. I made the 20th reunion, but sometimes our class couldn’t get their act together, so there was no 15th, 25th, or 30th reunion that I know of. The last reunion before this one was the 35th, which was the first time I’d really seen most of my classmates in a long time. Then the big FOUR-OH came up, and a lot more of them made the effort to show up from around the world, and reconnect with people they’d grown up with. Most of them were not just my high school classmates, but I first met them in elementary school over 50 years ago, so we went back a LONG ways. Like in every reunion, it’s a mixed bag: people who I’ve remained in contact with over 40 years, but seldom see; people who I’d lost touch with since 1972, but we had once been close friends; many people whom I barely knew in high school, but I had to be friendly and try to remember them; and a surprising number of “guests” who came to the reunion who were just plain weird (along with a bunch of drunks in the back of the room). Time had not been kind to many of us. Some had aged much more than others, so I could barely recognize them without trying to squint at their tiny name badges (complete with our senior photos, which further cruelly reminded us of how much we’d all changed). But I was also reminded how I was a skinny nerdy kid with thick black glasses back then, excluded from the major social cliques, and so I feel fortunate that time hasn’t turned my hair gray yet or caused much hair loss, and I’m no longer underweight. (But I’m even more near-sighted than back then). I also was shy and awkward, and had difficulties relating with people back then, whereas after 40 years I was much more comfortable with these people I’d known since childhood.

Going to a reunion after all these years reminded me of a lot of other things, too—some not so pleasant. Back then, our high school was highly stratified by test scores and grades. The most academically proficient kids were always in the same classes in nearly every subject: math, English, social studies, etc. Thus, I saw the same 30-40 kids in nearly every class I took from 7th grade onward, and barely even met the rest of the 535 students that graduated with me. So at the reunion, there were at most 10-20 people whom I knew very well—and the rest I barely knew at all, since we rarely were classmates in any subject (except gym, where as an uncoordinated awkward kid with thick glasses, the jocks loved picking on me). Back then, the academically oriented kids (words like “nerd” and “geek” were not in common use yet) like me were just as bullied, picked on, socially outcast and excluded from the ruling elite cliques of jocks and cheerleaders as they are in high school today—but we didn’t have the computer revolution to make our social exclusion easier to bear. There were no academic decathlons or other competitions of intelligence and knowledge, as there are today, to give us an outlet for achievement comparable to what the jocks had. I was such a trivia buff (I later appeared on “Jeopardy!” and beat Ben Stein in “Win Ben Stein’s Money”) that I would have thrived in that setting—but it didn’t exist yet. Instead, we banded together and found refuge in groups that didn’t exclude us. We had a killer chess club, and I was as high as number 3 on the ladder, but I could never beat our top two players—although we always beat our rival high schools in chess, while our rival schools creamed us in athletics. I started playing trombone in 6th grade, so I was a member of our bands and orchestras every year, and music was my refuge. My closest friends were in the band and were almost “family” to me. (I didn’t realize until movies like “Revenge of the Nerds” and “American Pie” that the high-school band is also a Hollywood stereotype for kids who are not part of the power cliques). Our band was really serious, though, even though our district wasn’t as rich or devoted to music as our arch-rivals in Arcadia, California. We could barely scrape together 50 musicians for marching band, while Arcadia had (and still has) hundreds at their disposal. Our band director, Mr. Joseph Acciani, managed to work our tails off and produce award-winning halftime shows, and top prizes at every parade we marched in, and our concert band and orchestra toured around the state each year by invitation. Out of that tiny group, we had four or five go on to all-state Honor Band and Honor Orchestra, and several went on to become distinguished professional musicians. We even marched in the 1971 Rose Parade (a 5.5-mile ordeal, the hardest thing I’ve ever done). Then as we graduated in 1972, Mr. Acciani left for another school, and the instrumental music program collapsed in short order (and our successors soon trashed the brand new uniforms we’d spent years in fundraising to purchase).

Yours truly in 2012, with a bunch of my classmates. I’m perhaps a bit less skinny and socially awkward after 40 years (although just as nerdy)

In many ways, my high school class was typical of the nation during a major change in society. Our school was one of the oldest in the region. It was established in 1901 as the first high school in the recently founded communities of Glendale, Burbank, La Crescenta, and Atwater Village. Thanks to our location in Entertainment Land, we claimed a number of actors and musicians among our famous alumni, such as John Wayne ’24 (known as Marion Morrison then), actress Kimberly Beck ’73 (two years behind me), actress Madeleine Stowe ’76, plus many more actors, actresses, directors, producers, screenwriters, and other Hollywood elite of the 20th century. We also turned out a number of famous musicians (we had the son of the legendary jazz guitarist Barney Kessel in our class, and many other famous musicians graduated from Glendale High), as well as many distinguished 20th century athletes, including world-class high-jumper Dwight Stones ’71 (one class ahead of me, he broke the world record when he was still in our school). In my own class, we had many that went on to careers as nationally known professional musicians and writers, calligraphers, educators at every level, computer geniuses, high-ranking state politicians, two students who won appointments to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, as well as many other careers. Knowing the state of education today, I realize how extraordinarily lucky we were to have nice stable supportive middle-class upbringings and a nationally-ranked high school which turned out some very good students, a high percentage of which went on to college and distinguished careers. Those among my class who are now teachers were complaining at the reunion how different things are now, how much more distracted, unmotivated, and unfocused most students are, and how much more likely even the best schools are to have incidents of violence and law-breaking and suicide. Society has changed in lots of ways, and it shows up first in the educational system.

Even though the kids today may have distracting backgrounds in some ways, my classmates were exposed to a lot of societal change, too: the Vietnam war and the radicalization of students across the country, the civil rights movement and its national effects (all of us vividly remember the Watts riots and how fearful we all were), the events of the JFK assassination (we were all in class in third grade when we heard the news from our crying teachers) to the years of the criminal Nixon administration, and the transformations of youth culture in general. Our generation was at the tail end of the Baby Boom and the radical ’60s and the hippie movement, so a glance through our yearbook reveals a lot of girls with very long hair and very short skirts, and fashion inspired by the hippie generation. During my senior year, our class forced the administration to get rid of lot of the dress code restrictions from decades earlier, so long hair was finally allowed for boys, along with shorter skirts and other superficial signs of rebellion. Yet in other ways, my high school class was highly conventional. We may have wanted to dress more like the hippies, but we came from fairly affluent upper-middle class families with mostly conservative parents and family backgrounds. We were never as rich as communities with elite schools like Beverly Hills, Palos Verdes, La Cañada, or San Marino, but we were no ghetto, either. We considered small pranks and a bit of wild driving to be the height of living dangerously, yet there were relatively few drugs (other than the ubiquitous pot) and other problems in our class. Even though we thought we were being rebellious, it was nothing compared to the outright riots and violence going on the university campuses around the U.S. at the time. This was partly because the Glendale we grew up in was one of the most conservative communities in the nation then. We used to joke that “the little old lady from Pasadena” in the Jan and Dean song really lived in Glendale, because our neighborhood then was very old and very white. The John Birch Society had its local offices in downtown Glendale, the KKK made appearances now and then (I remember at least one cross-burning), and our congressional district was so conservative that when our long-term Republican congressman, H. Allen Smith, decided to retire after 16 years in Congress, eight Republicans and one token Democrat ran for his seat. Most of my close friends and I had relatively liberal parents, so we were constantly sensitized to the problems of racism and discrimination and other societal problems that were part of our community and its ultra-right-wing political leanings.

One of the most pernicious practices of all was the de facto segregation that was going on at the time, although it was never publicly acknowledged. Most of the cities in southern California were slowly changing demographically, with greater numbers of Latinos and African-Americans moving up from poorer neighborhoods. Direct segregation was illegal, but the realtors and other powers that be in Glendale were diligent at discriminating against anything that threatened white dominance. We watched as next-door Pasadena increased its population of African-Americans (even as the Rose Parade Association discriminated against minorities), but our neighborhood didn’t change. (One consequence is that Pasadena High and Muir High, both in our league, beat us consistently with their superior athletes). Then I graduated in 1972 and moved on to college and grad school and lost touch with Glendale until I returned to teach at Occidental College in 1985. Meanwhile, during the late 1970s and 1980s, the de facto segregation policy was finally overcome. Glendale then transformed completely from a ultra-conservative, lily-white community in the midst of many other mixed communities, to one that was minority Anglo by the 1990s. The largest single ethnic group in Glendale is now the Armenians, and apparently we now have the largest community of Armenians outside Yerevan (over 30% of Glendale’s population now). Hispanics make up the second largest ethnic group (over 20%), followed by Koreans, Chinese, Filipinos, and other Asians (more than 20%), with Anglos a distant fourth. My 1972 graduating class had no more than a handful of Armenians, Asians, or Hispanics, but now the pendulum has swung the other way. I am proud to see my three sons go through the same school system I went through, and they are color-blind: they have friends of nearly every ethnic group, but the youngest two boys don’t even know what the label “Armenian” or “Korean” or “Hispanic” means yet. They are all just fun kids to play with.

In many ways, this experience is a microcosm of the changes in America as a whole. The country is becoming more and more non-Anglo, with minorities increasing in most states (especially the Hispanic community, which is now the majority in Los Angeles and in much of southern California). Meanwhile, the old Anglo community and their politics are now in the reactionary backwater, caught up in a pre-1960s fantasy world that lived only in the world of TV sitcoms like “Leave it to Beaver” and “Father Knows Best.” Although the upheaval of the Sixties was not as big in Glendale as it was elsewhere, nonetheless my classmates that went on to college were almost all radicalized by the crimes and scandals of Nixon and Kissinger, and the threat of being drafted to go to Vietnam. (I was lucky in that even though I had a bad draft number, the draft ended the first year I was eligible—plus I had a student deferment as well). Those changes of the Sixties—civil rights, women’s rights, the environmental movement—have become a permanent part of our society, although there are some who would try to roll back those changes and bring back the bad old world of the 1950s, when polluters could do anything, discrimination was law, and women were expected to toe the line of homemaker, and not allowed to work or pursue their own dreams. Our mothers had few choices, but the girls in my class were among the first generations to reap the benefits of the women’s movement. Other changes came much later. The gay rights movement is now at a stage where it is accepted by a slim majority of Americans, although again it is being resisted by the conservative, white religious minority. When we grew up in the 1960s, any mention of homosexuality was strictly taboo, and no one risked coming out of the closet for fear of severe repercussions. But we could all guess which teachers, and which of our classmates, were gay but couldn’t come out. Now most of them are out of the closet, and their lives are much better as a result.

But watching my classmates and I go through life and its vicissitudes is still a sobering experience. Like many Americans, many have gone through at least one divorce, and some more than one. Most us no longer have living parents, or our parents are in their 80s and just hanging on. Most of my classmates married right out of high school, and now have kids and grandkids, while I married very late, so my youngest child is now 7—by far the youngest child in that group of 58-year-old people. Many had gone through health issues (especially cancer), although very few had been smokers (our generation was one of the first to be warned about the dangers of smoking, so it was no longer cool when I grew up). Their stories made me so grateful for how much modern medicine has done to reduce mortality rates for many types of cancer and other diseases. Many had gone through huge life-changing crises, deaths of loved ones, or multiple careers. Some had settled for their first job out of school, and had never had a chance to pursue their dreams. A few lucky ones, like me, had pursued the career of their dreams, and had a long and rewarding life history. (I got hooked on dinosaurs at age 4 and never considered any other career but paleontology. But unlike now where every 10 year old loves dinosaurs, I was the ONLY one in my class who loved dinosaurs). And a surprising number had retired already, even though we are all about 58 in age. Many have chosen to pursue new careers or to get out of the dead-end careers they had started before.

But the most sobering thing of all was how many of our classmates were gone now. Two of them died in a car crash just weeks after we graduated, but almost 40 of them (out of 535 students over 40 years) have passed on now, largely due to car accidents and cancer. I’m not sure if that mortality rate is typical for a cohort like ours with relatively stable lifestyles, good healthcare, and low rates of smoking and alcoholism, but I’d be interested to know what the actuaries say.

So that’s my generation. We were not in the forefront in the change brought by the hippies of the 1960s, but many of us were involved in the social changes that occurred in the 1970s, and now our country is a completely different place. Our generation was fortunate in many ways, from our privileged upbringing, to being part of the new youth culture and enjoying the fruits of one of the greatest periods of popular music ever. We grew up with the Beatles, the Stones, the Who, the Doors, and great rockers of the late 60s; CCR and CSNY was played at every party I attended during my senior year. We may have been a bit too sheltered and affluent to experience the harsh realities of life in some parts of America, but some of us are now among the leadership that is trying to change the bad old customs we grew up with, and move America forward. Certainly, when you grow up in a lily-white ultra-conservative racist community, you can follow the path of your parents, or try to change the evils and inequities you see before you. I’m proud to say that most of my classmates chose the latter path.

A lot must have changed between 1968 and 1972. I was “brainy” (always in honors classes), but not “nerdy” or socially awkward and the same was true for most of my “honors” classmates. I was never bullied (or even teased) for my intellectual ability–quite the contrary, it made me more “popular”. I wasn’t a cheerleader type, but neither was I marginalized in any way. What brought about the shift to deriding those with academic ability?

I remain “popular” on fb with many classmates–especially guys I dated once or twice! Go figure. I’ve “kept myself up” as my grandmother would have said, but what these guys usually mention in their “comments” is how “smart” I was.

I’m sure it varies from region to region, and some school districts manage to make “nerds” cooler than others (I would presume this is true of academically competitive private schools especially). But if American movies and TV are to be believed, in most schools the jocks and cheerleaders are the most powerful cliques, and the brainy are marginalized–and so it was in my school. It may be even worse for guys than for girls, because the jock culture tends to physically bully the weaker kids. I”m not sure if girls do the same–they bully by catty behavior and social stigmas, which can be worse. And judging from my son’s high school, this has not changed–although the schools are trying to crack down on bullying and teasing and harassment more than ever…

If American movies and TV are to be believed, gangs break out into song and dance.

Public schools have de facto segregation. It’s Mexican gangs versus Black gangs versus Armenian gangs.

“Keep it cool, boy. Real cool…”

In my school it was the Nortenos vs. the Surenos. Even the Blacks and Anglos were expected to side with one or the other.

“You gotta keep ‘em separated.”

My (public) school culture was very different than Dr. Prothero’s – the top quarterback and head cheerleader were in my AP classes (we were also stratified by academic ability). The jocks and band mostly got along (the only way to get out of marching band was to play football – so the team had a number of band members on board). Most of the meanness came from a group of rich kids (mostly girls) who just had nothing better to do with themselves. They were easy to avoid if you picked the right classes. I never identified with John Hughes movies like everyone I went to college with seemed to, despite having attended public school in the area in which the movies are supposed to take place.

Wow! None of you look 58. I had always assumed that you were closer to my age, 43. Oh, thanks for all that social justice stuff.

Sorry my generations kinda “dropped the ball” on that one. All my punk rock, anarchist cohorts realized that they were confused fascists, and are now unwavering Ron Paul libertarians. :-/

There is only one reason to go to a class reunion, to bone the chicks you couldn’t bone when you were in high school. Judging from your picture and your own self description, I think it is safe to say that you couldn’t bone any. Hopefully at your reunion you finally put some points up on the board. Better late than never.

Really classy Nyar.

I bet you have women falling all over you.

Grow up.

Really CLASSY? Groan. Tmac, you made a bad pun and you should feel bad.

Donald, you won Ben Stein’s money? Cool! That must have felt especially good for a biologist, given Stein’s idiotic Expelled anti-science propaganda. (I don’t know which came first; maybe it felt especially good in retrospect.)

Ben Stein’s Money came first,and I actually use to like that show.It was several years later that I learned what an ass that Stein turned out to be.

Yeah, and if you watch the taping (it was Season 2, with Jimmy Kimmel still serving as sidekick), I beat Ben because there were several science questions in the final round, and he bombed. We all know now how abysmally ignorant of science he is. Believe me, after “Expelled” came out, I was GLAD I kicked his ass!