Happy Birthday, Stephen Jay Gould!

Two weekends ago, the country was absorbed in remembering the events of September 11, 2001, but September 10 was another anniversary: the 70th birthday of Stephen Jay Gould, paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, historian of science, Harvard professor, prolific writer and columnist, and probably one of the most influential public scientists of the 20th century. A number of prominent evolutionary biologists and bloggers paid tribute to him, including P.Z. Myers, Jerry Coyne, and others. Even though Steve lived to the age of 60 and passed away on May 20, 2002, most of us were shocked when he was stricken so suddenly by cancer and wasted away to nothing in a matter of weeks. In spite of his rapid decline in health, during his final semester he gamely kept traveling up from his New York apartment to Harvard to teach his classes, even though he was so weak he could barely stand. Though he accomplished more in his lifetime than any other scientist of his generation (books, essays, research, scientific papers, etc.), most of us felt that his death at 60 was premature and that he had so much more to offer us had he lived his fullness of years.

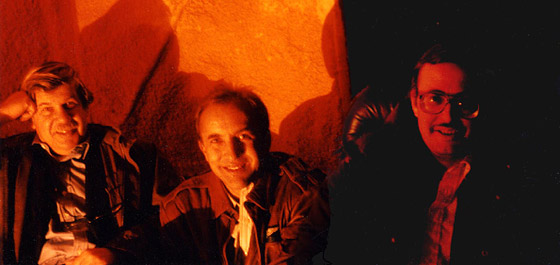

Yours truly (right) with Gould (left) and Michael Shermer (center) at Mount Wilson Observatory, 2001.

I should explain to the reader of my personal perspective in this matter. Although I was never formally his student, Stephen Jay Gould was a friend and mentor to me while I was at Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) as a graduate student from 1976-1982. When I arrived at the Columbia/AMNH program, all the grad students heard the legends of Steve when he was a grad student in the same program two generations earlier. Each year, the stories got more and more amazing: how he outshone all the other students with his brilliance, published his first paper early in grad school, wrote entire papers in a few hours of work, wrote his entire dissertation in a few hours/days/weeks when his advisor Dr. Norman Newell thought he should finish and defend, and so on. His were enormous shoes to fill, and we all felt his shadow when we were being evaluated as students. I saw him on numerous occasions when I was a grad student, not only at professional meetings, but also when he came down to Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory to see for himself the work that Dave Lazarus and I (Lazarus et al. 1982) were doing on gradual evolution in plankton (he was more open-minded that you would expect), or when fellow student Paul Sereno and I paid a visit to him at Harvard while we were working on a project on allometry and dwarfing in mammals (Prothero and Sereno 1982). Subsequently, he was extremely supportive to me during my professional career, recommending me for a Guggenheim Fellowship (which I got, thanks to him), plugging my work in his Natural History columns several times, and graciously replying to my letters whenever I had an idea that truly required his attention. When my job and my department at Knox College were about to be eliminated in 1983-1984, he spoke out not only in front of the audience at the GSA meeting, but also wrote letters on our behalf to try to reverse the decision. Thus, I cannot claim to be impartial about Steve, but I do speak from personal experience and from watching paleontology change over the past 40 years.

In many ways, Gould’s brilliance and success made him a target for fools and creationists, and turned him from merely a paleontologist into a media celebrity on par with Carl Sagan and Steven Hawking. Like Hollywood celebrities and other high-profile figures, Gould did not have as much privacy as he would have liked, dealt with the constant distraction of people demanding his time and attention, and everything he said or did was scrutinized. Shermer (2002) analyzes some of the criticisms of Stephen Jay Gould, and dissects his prodigious volume of writing about his favorite topics, and even the elements of his writing style. Much of the criticism stems from scientific jealousy and the complaint that Gould’s writing was too popular (the so-called “Sagan Effect”). As Raup (1986) noted, Carl Sagan was denied many honors (such as election to the National Academy of Sciences) in his field and dismissed as just a popularizer of science, rather than as a research scientist. However, Shermer showed that Sagan continued to publish peer-reviewed articles at the same pace, even as he worked on “Cosmos” and wrote trade books. By contrast, Gould actually published more peer-reviewed science than he did books or essays for the general public. Gould’s productivity in every category (peer-reviewed articles, books, popular essays, book reviews, and the like) outstrips all the big-name scientists of his era, including Carl Sagan, Ernst Mayr, E.O. Wilson, and Jared Diamond. Gould was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, and became one of the most respected scientists in America. He served as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the Paleontological Society, and the Society for the Study of Evolution (SSE). Gould received dozens of honorary degrees, and won nearly every award he was eligible for, including the MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called “genius award.” As a true measure of his fame across the culture, Gould was portrayed by a cartoon of himself (providing his own voice) on The Simpsons. Another episode of the same show that aired the week he died was dedicated to his memory.

Ironically, now people complain that the problem with science literacy in this country is that there are too few popularizers, and too few scientists who step out of their ivory towers to convey the importance of science for the general public. These critics include marine biologist Randy Olson, who made a documentary about creationism and scientific arrogance entitled “Flock of Dodos”, or Chris Mooney and Sheril Kirshenbaum, authors of Unscientific America: How Scientific Illiteracy Threatens our Future. It seems you can’t win. You can become a Carl Sagan or Stephen Jay Gould and have your professional peers snipe at you out of jealousy for your popularity, or you can retreat to your lab and let the culture critics complain that scientists are too aloof.

But the area where Gould is best known and most controversial is his lifelong quest to expand evolutionary biology, and bring paleontology to the “High Table” of evolutionary biology. As Gould (1983) himself pointed out, paleontology was virtually irrelevant to evolutionary theory from Darwin’s time until the 1940s. During the start of the Neo-Darwinian synthesis in the 1930s and 1940s, Gould (1983) argued that paleontology became subservient to evolutionary genetics, especially due to the work of paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson and his book Tempo and Mode in Evolution (1944). Although that book debunked a lot of false notions of earlier paleontologists, it also reduced all of the fossil record to just examples of gradual change and simple natural selection as preached by the Neo-Darwinists. When the Society for the Study of Evolution was founded in 1947 (with Simpson as first president), paleontological papers were published alongside those of geneticists in their flagship journal, Evolution.

By the time Gould’s generation of paleontologists came of age in the 1960s, paleontology was truly subservient to genetics. Few paleontology papers were published in Evolution any more. Both Gould and Niles Eldredge remarked that they came to the Columbia/AMNH program to study with Norman Newell and document evolutionary patterns in the fossil record, and found to their surprise that the expected pattern of gradual evolution was extremely unusual. As they detail in their books (Gould 2002; Eldredge 1995), the famous 1972 “punctuated equilibrium” paper was accidentally assigned to them by editor Tom Schopf, who wanted a review of speciation theory, not an area that Gould had worked on at that point. The “punctuated equilibrium” paper led to the realization that paleontologists who had long been trying to document gradualism had not kept up with implications of the allopatric speciation model developed 30 years earlier by Ernst Mayr and others during the Neo-Darwinian synthesis.

Once “punctuated equilibrium” became a hot topic, it dominated the journals and scientific debates. I vividly remember sessions at each professional meeting during the 1970s as knock-down drag-out fights between the old-guard gradualists and the “Young Turks” led by Gould, Eldredge, and Steve Stanley. Gould and Eldredge (1977) effectively answered most of the early criticisms of the “punctuated equilibria.” By the mid-1980s, a consensus had emerged from the paleontological community that nearly all metazoans (vertebrate and invertebrate, marine and terrestrial) show stasis and punctuated speciation through millions of years of geologic time and strata, with only minor possible examples of gradual anagenetic change in size (Geary 2009; Princehouse 2009; Hallam 2009). That has been the accepted view of paleontologists for better than 20 years now.

Yet you would never know this by looking at the popular accounts of the debate written by outsiders, who still think it is a controversial and unsettled question. Even more surprising is the lack of response, or complete misinterpretation of its implications, by evolutionary biologists. Since the famous battle at the 1980 Macroevolution Conference in Chicago, neontologists have persisted in misunderstanding the fundamental reasons why paleontologists regard punctuated equilibrium as important. Many have claimed that people like Simpson (1944) or other were thinking along the same lines, or that gradual change on the neontological time scale would look punctuated on a geologic time scale. They miss the point of the most important insight to emerge from the debate: the prevalence of stasis. Before 1972, paleontologists did overemphasize examples of gradual evolution, and they expected organisms to gradually change through geologic time, as they do on neontological time scales. But the overwhelming conclusion of the data collected since 1972 shows is that gradual, slow, adaptive change to environments rarely occurs in the fossil record. The prevalence of stasis is still, in my mind, the biggest conundrum that paleontology has posed for evolutionary biology, especially when we can document whole faunas (Prothero and Heaton 1996; Prothero 1999; Prothero et al. 2009) that show absolutely no change despite major changes in their environments. That fact alone rules out the “stabilizing selection” cop-out, and for years now paleontologists and neontologists alike have struggled to find (unsuccessfully, in my opinion) for a good explanation for why virtually all organisms are static over millions of years despite huge differences in their adaptive regime. The gradual adaptation of fruit flies and Galapagos finches may be good examples of short-term microevolutionary change, but they simply do not address what the fossil record has shown for over a century. This only became apparent when Gould, Eldredge, Stanley and others began to talk about species sorting, decoupling microevolution from macroevolution, and the importance of hierarchical thinking in evolutionary biology. Many neontologists appear to have a relentlessly reductionist attitude and simply “don’t get it,” no matter how many times and how clearly it has been explained to them.

Thus, almost 40 years since the original 1972 paper, we have a different kind of “two cultures” phenomenon of people with different mindsets talking past one another. Paleontologists have agreed for decades now that the prevailing message of the fossil record is stasis despite big changes in the environment. Based on the literature (Sepkoski and Ruse 2009), we have undergone a “paleontological revolution” with a less subservient approach to evolutionary biology. Most paleontologists are in agreement with Gould’s cry for the importance of species as entities, species sorting, and the hierarchical approach to macroevolution. As Gould and Eldredge wrote in 1977, “why be a paleontologist if we are condemned only to verify what students of living organisms can propose directly?” Although Gould was the loudest voice for paleontology’s claim to an important role at the evolutionary High Table, any review of the books, papers, and presentations that paleontologists are releasing shows a non-neo-Darwinian, more pluralistic approach to evolutionary theory, especially when it comes to concepts like evolutionary paleoecology, mass extinction theory, and coordinated stasis.

Yet I look at what neontologists write about the topic, and it seems as if they simply cannot grasp what paleontologists have said over and over again. When I (Prothero 2003) wrote a review of two recent evolutionary biology textbooks, it was apparent that the authors had no clue about the implications of punctuated equilibria, species sorting, and the stability of species despite environmental changes. Instead, their approach to the topic revealed a profound misunderstanding of the important points, distortions of what is being claimed and what is not, and pointless critiques of old outdated arguments and trivial side issues, as if they were still reading the debate as it stood in the 1970s. Now and then you find concessions, such as Mayr (1992, 2001) admitting that the prevalence of stasis is a puzzle that has no simple answer, but by and large the neontological community still “doesn’t get it.” Paleontologists have been trying to communicate their distinctive perspective for a generation, culminating with Gould’s (2002) magnum opus, published just as he was dying. Yet the harsh reviews of Gould (2002) by neontologists showed that they still didn’t understand the critical issues and were rehashing issues that had been resolved by paleontologists 30 years ago. The journal Evolution still publishes almost no contributions by paleontologists, and the meetings of the SSE I have attended just reinforced how large the culture gap had grown. If these bellwethers are representative of the relationship between paleontologists and neontologists, then it seems clear that paleontology has still not claimed its rightful seat at the “High Table”.

I’m not sure why this is so. It could be the huge conceptual and culture gap between paleontologists and neontologists, and how the differences in timescale shape their thinking. It could be an artifact of academic Balkanization, where paleontologists are still largely in geology departments and rarely encountered by evolutionary biologists. It could be professional territoriality and turf wars. If Gould (1980, 2002) was right and the best way to understand macroevolution comes from the fossil record, then a lot of fruit fly research is irrelevant. Even Simpson (1944) made this point: “Experimental biology . . . may reveal what happens to a hundreds rats in the course of ten years under fixed and simple conditions, but not what happened to a billion rats in the course of ten million years under the fluctuating conditions of natural history. Obviously, the latter problem is more important.”

In May 1984, the evolutionary biologist John Maynard Smith wrote in Nature, “The palaeontologists have too long been missing from the high table. Welcome back.” But judging from the way in which paleontology is presented in biology textbooks, the lack of paleontology papers in Evolution, and the harsh response to Gould’s (2002) final work, I think this welcome was premature. Now that the most articulate spokesman for paleontology has been gone for nine years, I doubt that this will ever change.

Even 9 years after his death, we paleontologists still miss Steve. I hear it all the time at paleontology meetings. Just like everyone can remember what they were doing and where they were when they first heard about the 9/11 attacks, every paleontologist I know vividly remembers how and when they heard the news of Steve’s death. Paleontology may never have a spokesman with such a high public profile again. His influence is still in the culture, as shown by the fact that bloggers commemorated his 70th birthday last weekend, and that his ideas are still being debated almost a decade after his death. Perhaps the ultimate tribute to him was “Project Steve” of the NCSE, where they tallied up scientists who accepted evolution whose names were Steven, Stephen, Stephan, Stephanie, or other cognates—and those names alone far outstrip the number of “scientists who question evolution” that the creationists are always touting. It is the ultimate send-up of these silly creationist efforts, and just the kind of clever idea against Gould’s old nemesis that he would appreciate most.

Happy Birthday, Steve!

Literature Cited

- Eldredge, N. 1985. Time Frames: The Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Eldredge, N and SJ Gould. 1972. Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism. In Models in Paleobiology. Ed. by TJM Schopf. San Francisco: Freeman Cooper. pp. 82-115.D

- Geary, DH. 2009. The legacy of punctuated equilibrium. In Stephen Jay Gould: Reflections on His View of Life. Ed. by WD Allmon, PH Kelley, and RM Ross. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pp. 27-146.

- Gould, SJ and N Eldredge. 1977. Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered. Paleobiology 3:115-151.

- Gould, SJ. 1980. Is a new and more general theory of evolution emerging? Paleobiology 6: 119-130.

- Gould, SJ. 1983. Irrelevance, submission, and partnership: the changing roles of paleontology in Darwin’s three centennials, and a modest proposal for macroevolution. In Evolution from Molecules to Men. Ed. by DS Bendall. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 347-366,

- Gould, SJ. 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Hallam, A. 2009. The problem of punctuational speciation and trends in the fossil record. In The Paleobiological Revolution. Ed. by D Sepkoski and M Ruse. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Pp. 423-432.

- Lazarus, DB, JD Hays, and DR Prothero. 1982. Evolution in the radiolarian species-complex Pterocanium. Proceedings of the 3rd North American Paleontological Convention, 2: 323-328.

- Maynard Smith, J. 1984. Palaeontology at the high table. Nature 309:401-402.

- Mayr, E. 1992. Speciational evolution or punctuated equilibria, In The Dynamics of Evolution: the Punctuated Equilibrium Debate in the Natural and Social Sciences. Ed. by A Somit and SA Peterson. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 21-53,

- Mayr, E. 2001. What Evolution Is. New York: Basic Books.

- Mooney, C and S Kirshenbaum. 2009. Unscientific America: How Scientific Illiteracy Threatens our Future. New York: Basic Books.

- Princehouse, P. 2009. Punctuated equilibrium and speciation: what does it mean to be a Darwinian? In The Paleobiological Revolution. Ed. by D Sepkoski and M Ruse. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Pp. 149-175.

- Prothero, DR. 1999. Does climatic change drive mammalian evolution? GSA Today 9(9):1-5.

- Prothero, DR. 2003. Did paleontology ever sit at the High Table? A review of “Genetics, Paleontology, and Macroevolution,” by J.S. Levinton, and “Evolution,” by M.W. Strickberger. Priscum 12 (1): 21-23.

- Prothero, DR and PC Sereno. 1982. Allometry and paleoecology of medial Miocene dwarf rhinoceroses from the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain. Paleobiology 8(1): 16-30.

- Prothero, DR and TH Heaton. 1996. Faunal stability during the early Oligocene climatic crash. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 127:239-256.

- Prothero, DR, KR Raymond, VJ Syverson, and S Molina. 2009. Stasis in late Pleistocene birds and mammals from La Brea tar pits over the last glacial-interglacial cycle. Cincinnati Museum Center Scientific Contributions 3: 291-292.

- Raup, DM. 1986. The Nemesis Affair: The Story of the Death of the Dinosaurs and the Ways of Science. New York: WW Norton.

- Sepkoski, D and M Ruse (Eds.). 2009. The Paleobiological Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Shermer, MB. 2002. This view of science: Stephen Jay Gould as historian of science and scientific historian, popular scientist and scientific popularizer. Social Studies of Science 32(4): 489-525.

- Simpson, GG. 1944. Tempo and Mode of Evolution. New York: Columbia University Press.

Absolutely wonderful. Thank you Dr. Prothero.

Just by chance I have been listening to Dawkin’s “The Blind Watchmaker” where an entire chapter is sort of “the other side”. Dawkins has nothing but professional praise for Gould and Eldredge in The Watchmaker and it is emphatic about the point you make; punctuated equilibria is not about sudden change but about exposing the long stasis of evolution. What Dawkins seems to argue is that the paleontologists like Gould chose to popularize the “punctuated” part. This is the recollection I have from reading all of Gould’s books. (As an aside, “Eight little piggies” was instrumental during my graduate career. My dissertation was about limb development).

Also, Dawkins points out that the importance of stasis is not newly understood and that Darwin himself understood how important was stasis. This is opposed to the misconception that Gould and Eldredge proved neo-Darwinism “wrong”:

“… natural selection will generally act very slowly, only at long intervals of time, and only on a few of the inhabitants of the same region. I further believe that these slow, intermittent results accord well with what geology tells us of the rate and manner at which the inhabitants of the world have changed.” (Darwin, Ch. 4, “Natural Selection,” pp. 140-141)

But I must here remark that I do not suppose that the process ever goes on so regularly as is represented in the diagram, though in itself made somewhat irregular, nor that it goes on continuously; it is far more probable that each form remains for long periods unaltered, and then again undergoes modification. (Darwin, Ch. 4, “Natural Selection,” pp. 152)

http://theobald.brandeis.edu/pe.html

The rivalry between Gould and Dawkins, or the paleontologists Vs neontologists is a battle of intellectually stimulating giants that us outsiders get to enjoy. I wish all rivalries would benefit human knowledge this much! It showed me personally that in true knowledge there is no such thing as splitting hairs.

Yes, exactly. The frustrating thing for paleontologists is the neontologists’ narrow focus on fruit flies and lab rats, and claiming that the Galapagos finch model is the ne plus ultra explaining all of speciation, when the fossil record clearly shows that the Galapagos finches are probably NOT a good model of how species really form, or how insensitive species really are to climate change. Nonetheless, that’s what is taught in biology across the country, and biology textbooks either get “punk eek” wrong or ignore it entirely.

One other thing to note, an idea of Gould’s that has less acceptance today — that life is contingent.

I totally agree, and think the “progress” view of evolution held by Dawkins and many others is simply wrong. So is the claim of Dennett and others that evolution is algorithmic.

Very true–Gould had already factored in Dawkins’ concept of “progress” by pointing out that if you start with bacteria, life can ONLY go in the direction of larger and more complex. This is hardly “progress” simply random drift away from a barrier of minimum size and complexity. And Conway MOrris’ concepts are highly questionable (see my review of his book) and tainted by his religious biases…

Donald: Agreed on Morris, too.

On issues of evolution’s contingency, or not, and its being non-algorithmic or algorithmic, how much of this, on the pro-algorithmic/anti-contingency side, overlaps with Gnu Atheism?

Have any of Gould’s followers or associates responded to this paper PLoS?

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/14/science/14skull.html

Particularly this claim from the NY Times article:

But Ralph L. Holloway, an expert on human evolution at Columbia and a co-author of the new study, was less willing to give Dr. Gould benefit of the doubt [about Gould's criticism of Morton's work].

“I just didn’t trust Gould,” he said. “I had the feeling that his ideological stance was supreme. When the 1996 version of ‘The Mismeasure of Man’ came and he never even bothered to mention Michael’s study, I just felt he was a charlatan.”

See also “Neo-Lysenkoism, IQ, and the press”, by Bernard Davis.

http://www.nationalaffairs.com/doclib/200604071_issue_073_article_3.pdf

I can’t speak for the dead, nor would any of his students or friends or colleagues presume to do so. I’m sure if Steve were alive, he would be able to counter these accusations in his own inimitable way–and just because he’s not alive to answer them does not mean that we should assume his critics are right.

From personal knowledge, when I was at Columbia I knew both Steve and Ralph Holloway well, and there’s more there than just professional rivalry going on. So take Holloway’s opinion with a grain of salt. I also know from personal knowledge that a LOT of Gould’s work was reporting on other studies (just as we all do when we popularize anyone’s research other than our own). He did not do most of the actual measurements in “The Mismeasure of Man” but reported on other’s measurements and how they changed with different types of materials placed in skull cavities.

Paul Sereno and I discovered a similar issue in a paper he did which we had to recheck–it was based on other people’s data that turned out to be flawed, which Gould did not have the time or opportunity to check. That’s the way it is in science: most of the time we trust that our colleagues have done their job properly if the paper passed peer review, since none of us has time to recheck and remeasure everything that we report on. Gould told us that the particular paper, he was in a big rush to turn something in on deadline, so he used data others had given him, and replotted and extracted something new from it. That’s the price one pays for being as busy and productive as Gould. He had to write an enormous amount each month to keep up with the demand, so he may have used other people’s data once in a while that (without knowing otherwise) he shouldn’t have trusted.

Given the serious nature of the accusations in the NY Times article, I’m shocked that there hasn’t been more a public response from Gould’s defenders (at least that I am aware of).

Again, I think people have a mistaken idea about Gould and his students and colleagues. Gould didn’t have a “lab” where his students all worked on the same projects as their mentor, and were obliged to defend his work. Each student did a project entirely unrelated to Gould’s research, and he just served on their committee and gave advice. Most of Gould’s work (especially the work in question) was his and his alone, and none of his former students and colleagues are in the position to defend it or second-guess it, let alone try to get into Gould’s mind posthumously and figure out what happened. When he was alive Gould defended himself quite well and needed no help. Since he can no longer do it, and none of his students or colleagues are in a position to do it, we are leaving the issue alone. Gould’s reputation rests on his entire body of work, and his gigantic influence on science and especially paleontology and evolutionary biology, not just on one project that may or may not have been done correctly.

If Holloway could defend Morton’s work, then surely someone can defend Gould’s work.

A Christian friend noted the red tint in your photo and suggested it implied your future in hell.

Seriously.

Next time I’ll Photoshop in some horns on our heads…

Seriously, the shot was taken at night in the open dome of the third telescope at Mt. Wilson using available light, which must have had some weird color balance to affect the film (NOT a digital image originally). This is probably because the lights in that telescope dome had to be a color that did not ruin the light reception of the telescope itself…

Dr. Prothero, thank you for writing such an eloquent piece on one of my scientific heroes. Even though I am an electrical engineer, I have had a lifelong passion for biology and have read most of Dr. Gould’s writings with a mixture of admiration for his knowledge and jealousy for his facility with the English language!

Also, I am shocked that Carl Sagan was not a member of the National Academy of Sciences! I know that one is nominated/elected by one’s peers to this esteemed organization, but I find his exclusion to be an act of extreme churlishness. Surely, I would expected that there would have been a quorum of members who would have appreciated his monumental contributions to improving the state of human knowledge as a contribution worthy of consideration for membership. What a travesty!

Awesome. SJG the fraud. I have long divorced myself from the skeptic community for issues JUST LIKE THIS. Skeptics are just as dogmatic about their beliefs and gods (in this case, SJG) as the religionists. Scammed by one of your own. Haha! Next time try you try science, try it WITHOUT your half-baked, biased, politically correct presumptions on human differences. If I want biased dogmatic pseudo-science, I’ll get it from the religionists!!!

As a skeptic, I feel hero worship is a dangerous game. It should be all about the data. Science changes and we, as skeptics, have a duty to evaluate the best evidence in an impartial manner. Canonizing one of “ours” create insurmountable prejudice with respect to his body of work.

SJG and, in general, the genetic basis of intelligence makes some in the skeptic community (http://www.skepdic.com/iqrace.html) freak out and revert to straw man arguments, argument from authority and, IN PARTICULAR with this issue, argument from final consequence.

SJG was proven, at least once, to be a sloppy scientist. What needs to happen is the skeptic community need to re-evaluate his body of work for more evidence of bias. Worshipping the guy is a bit too christian, wouldn’t you say?