Dancing into an uncertain future

Eager young VP students dance through the night at the after-meeting party. (Photo by R. Hunt-Foster).

Last November, the 73rd annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) was held here in Los Angeles. SVP is my professional society, since my primary training and research is fossil vertebrates (especially fossil mammals like rhinos, peccaries, camels, horses, and others). My first SVP was the 1977 meeting, the last time it was held here in Los Angeles, when I was just a beginning graduate student. Since then, I’ve been to every meeting of SVP, a streak of 36 years in a row. It’s my lifeline, and I wouldn’t consider missing it for anything. Once a year I get to see all my closest professional friends and colleagues, people I spent months in the field with, former officemates from grad school, and find out the latest news about people I’ve known for 30 years or more. I also present my own research (I always do at least one presentation, and sometimes my name is on several more by my students), and I usually get to see my former students as they grow and thrive in their own careers. For five years (1999-2004), I was the Program Chair, running the entire meeting and producing (editing, typesetting, etc.) the abstract volume with over 600 individual abstracts. At that point, I couldn’t miss the meeting for anything, including my brother’s wedding (I told him in advance NOT to schedule it to conflict with SVP). Most importantly, I go each year to get some positive feedback and affirmation that my 40 years of research and scholarship is valued and means something to people who appreciate it. This is essential when you spend the other 51 weeks of the year in a hostile department where they don’t appreciate you and try to tear you down at every opportunity.

Over the 36 years between the two Los Angeles SVP meetings, I’ve seen enormous changes in our profession. When the SVP was first founded in 1940, it consisted of at most a dozen men and two women, and their meeting was small enough that they could all get together in Al Romer’s office at Harvard (their first venue) and take turns chatting about their latest projects. When I first started in 1977, the meeting was still small, as was the profession. The total attendance was less than 200, nearly all old white male professionals with jobs in museums or top universities, plus a few graduate students. Although jobs were scarce, only a few institutions were training Ph.D.s in VP, so the job market wasn’t severely glutted. The meeting barely lasted 3 days, with nearly everyone attending giving an informal presentation, many without slides. There was only one session, so most of us sat through nearly every talk to learn what was going on with fossil fish or fossil amphibians as well as within our own specialities. There were at most half a dozen dinosaur paleontologists in the entire profession, and their talks were a tiny part of the overall program. The meeting had a short one-page program listing the order of speakers, but there were no abstracts or bound volume containing them published by the society. Best of all, the profession was so tiny that after attending a few SVP meetings, I knew nearly everyone in the field, and they knew me.

The joy and excitement of studying what they love is palpable in their faces (along with the effects of a lot of alcohol). (Photo by R. Hunt-Foster).

Over the years, both the meeting and the SVP have grown dramatically. Last year’s meeting in Los Angeles topped 1400 participants, near the previous records set by meetings in Austin, Texas, and Las Vegas, Nevada. SVP’s total membership is over 2300, a dramatic increase over just a few decades. The meeting is now a huge four-day extravaganza, with three and sometimes four concurrent sessions running in different rooms (often blocks apart, so you can’t jump from one to the other), and almost 700 abstracts presented (both platform talks and posters), and a thick abstract volume both on line and printed on demand. When I was Program Chair for five years (the longest term anyone has held this impossible job), I had to review and screen them all, then program them into a sequence that would minimize the conflicts between talks in concurrent sessions that might appeal to the same audience. The nature of the program has changed as well: now the biggest of the three main rooms is a dedicated full-time dinosaur session, running with non-stop dinosaur talks from beginning to end of the meeting (mostly to appeal to the amateurs at the meeting, who care only about dinosaurs). Another meeting room is nearly always mammal-oriented talks, and the poor fish, amphibians, and non-dinosaurian reptiles get the remaining scraps of program time.

The meetings 30 or more years ago might have had an opening reception in the host museum on the first night, and a banquet on the last night. Now the meeting has non-stop social events each evening. There is not only a huge reception opening night at the museum, and a big banquet the last night when awards are given, but also a huge auction of VP-related paraphernalia (fossil casts, publications, art, knick-knacks) to raise money for the SVP and for students, another night devoted to a big reception for the students only, plus meetings of many smaller interest groups (Women in VP, LGBT in VP, Preparators’ Sessions, Blogger Groups, Government Employees in VP, and many, many more). The auction is a very lively event, with the entire auction committee creating costumes in a similar theme: Star Wars, Superheroes, Indiana Jones, and many others; this year, they were all characters from Hollywood horror movies. First there’s a silent auction, then the live auction begins once everyone is suitably drunk, and many are bidding way too much for something they could easily get much more cheaply elsewhere. (All items are donated, and all proceeds go to the SVP student fellowships). In recent years, they’ve added a huge after-party late into the final evening after the banquet is over, where the younger members dance the night away until 3 or 4 a.m.

The SVP Auction Committee, this year all in costume to represent characters from Hollywood horror movies. (Photo by R. Hunt-Foster).

A lot of this huge expansion of the SVP meeting has come through the growth in amateur attendance, since SVP is one of the few professional societies that encourages amateurs to join us. Almost half of the 1400 attendees are amateurs, who just want to see talks about dinosaurs, and rub shoulders with famous dinosaur paleontologists. Fewer than 200-300 of the 1400 attendees are VPs with jobs at museums or major universities. But the largest component of the attendance is the students.

All this youthful vitality and enthusiasm is wonderful, and I’m glad to see increasing numbers of people as excited about VP as I am. After all, I’m one of those kids who got hooked on dinosaurs at age 4 and never grew up! I knew I wanted to be a paleontologist as soon as I knew what that word meant. Back when I grew up in the 1950s and early 1960s, however, I was the only kid I knew who loved dinosaurs. Today nearly every kid goes through a dino-mania phase before age 10. But I also look at all the new young faces at the meeting with a touch of melancholy as well. Almost 40 years in the profession have taught me some of the hard realities, especially regarding employment. Despite a ten-fold increase in membership and meeting attendance, the job market for VPs has shrunken in that same time frame. The post-Baby Boom years since the 1970s meant most universities had fewer students and hired fewer faculty, and most did not replace the VP on their staff with someone of similar training when the VP died or retired or left. This was true when I finished my Ph.D. and graduate school in 1982, and there were at least 10-50 applicants for every job even remotely connected to VP. Now a job listing nets 100-500 applicants. The plum jobs at the few museums with VP collections open up once in a decade, and I remember spending a lot of time as a student wondering when certain people were going to retire. In the meanwhile, the few survivors of my cohort that DID get jobs took employment wherever we could find it. I spent my entire career in small liberal arts colleges (Vassar, Knox, and then Occidental College for 27 years) where they gave us heavy teaching loads and showed no interest in my research or publications. Ever optimistic that my hard work and publication would pay off, I was always applying for university or museum jobs that opened up in hopes of moving to a place that supported and appreciated research. Now the job market is so bad that any kind of employment—community colleges, environmental consulting firms, teaching human anatomy to medical students, even if much lower-paying that the traditional university professor’s salary—is better than unemployment. Never mind aspiring to one of the plum research positions at major museums! As the recent problems at the Field Museum in Chicago, and now the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh have shown, these jobs are no longer very secure. All it takes is a few incompetent administrators to botch up the museum’s planning and finances, and the first one out the door are the curators who perform the essential research function at a museum (not the administrators who actually caused the problem in the first place).

Every student who has come to me, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed and eager to pursue a VP career, gets my version of “The Talk” early on, before they have committed too much. I try to explain to them how daunting the odds are, how hard they will have to work, how they will have to publish like crazy while still in grad school to have at least a small chance of making the cut—and how even then, there is so much politics and cronyism and other stupid stuff going on that the most qualified candidate (as I often was in many searches) doesn’t get the job. Sadly, most of the rest of the profession doesn’t seem to realize that students need to hear this information early before they get too far in the profession. Over and over again at the meeting, I’m introduced to new graduate students who have no idea what they’re up against and how long the odds are, because no one who advises them told them the truth. So many academic institutions are now advertising themselves as places to get a graduate degree in VP. Yet only a handful of the elite institutions with multiple VP faculty or curators and sizable research collections of unstudied fossils (typically, it’s Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History where I was trained, plus Harvard, Yale, Michigan, Berkeley, Texas, and just a few others) turn out students who get jobs. Tiny podunk colleges with one VP staffer and limited research collections are now turning out dozens of students with no chance of getting a job, given their limited training, and lack of publications as a grad student. Yet they keep advertising and luring more and more students to enroll in their programs, never taking responsibility for what happens at the other end.

I was always glad that I was trained in one of the top programs in the country at Columbia/American Museum, and that my advisor, Malcolm McKenna, took at most one or two students a year, so there were never more than 3-5 of us at a time. We all got unlimited access to the best collections in the world, and plenty of time to do our own research and publish. Not surprisingly, the American Museum program has by far the best per capita success rate, with nearly every student who finished there getting a decent job. In fact, many of the curatorships in major museums (Bob Emry at the Smithsonian; John Flynn at the Field Museum and now as McKenna’s successor at the American Museum; Bob Hunt at the Nebraska State Museum; Bruce MacFadden at the Florida State Museum; Margery Coombs at the Beneski Museum, Amherst; Rich Cifelli at the Stovall Museum, University of Oklahoma; Tom Rich, Pat Rich, and Mike Archer at museums in Australia, and many others) were or are occupied by former McKenna students. No other academic institution can make such a claim.

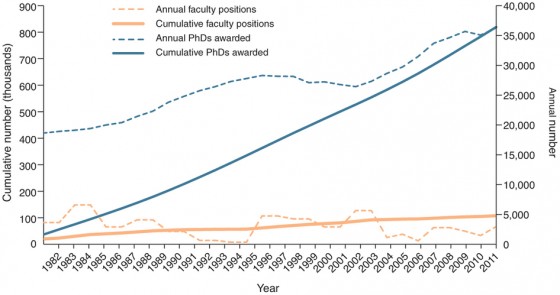

A plot showing the growth in number of Ph.D.’s (blue lines) versus the slow change in the academic job market (yellow lines) (From Schillebeeckx et al., 2013)

All of this was painfully obvious as I saw the ranks of clueless students grow and the job market shrink. Yet even I was not aware of how badly the trend for academic employment has become. A new study by Schillebeeckx et al. (2013) points out that Ph.D.s are being minted far in excess of the slow rate of growth of academic jobs. And this is for fields like molecular biology and chemistry and certain types of physics, which have generally had plenty of employment and funding, and lots of non-academic options to pursue. For the VP who has limited options of academic employment (geology, biology, or med school anatomy programs are the main choices), this is positively alarming. Basically, anyone pursuing a Ph.D. and wishing to remain in VP must be willing to take any opportunity that comes along, no matter how badly paid or how far it is from a plum research job. That’s going to be a bitter pill for these bright-eyed, bushy-tailed students, so full of energy and excitement and promise at their cool field of study, where they get to work on dinosaurs and other amazing prehistoric beasts. But after almost 40 years in this profession, I’ve watched a lot of outstanding students undergo huge psychological stress as they dealt with the realities of the job market that their advisor never warned them about. I’ve seen the cost in human capital, and in disappointment and ruined lives. I wish it were otherwise, but I have little power to warn all these students who are not being told the truth.

This recent article, entitled “The Odds are Never in your Favor”, in The Chronicle of Higher Education compares searching for academic jobs to “The Hunger Games”: young people pitted against each other in a battle for survival, cruel and unfair judging by the older generation determines your fate, poor odds of making it out alive, disappointment is the most likely ending. I wish it were a joke…

And so, I tell my story here. Pass it on to any student who thinks they might want to study dinosaurs for a living.

Posted on behalf of Andrew Farke (who can’t seem to get through the moderation queue):

An excellent post, Don–there is much that is true here! (I speak as someone who is gainfully employed at a small museum, now 6 years out of grad school). My only minor addition to what you say above is that I wouldn’t discourage students from seeking employment at non-R1 institutions, if that is what they genuinely want. A big problem in academia is that students are often told that they are failures unless they get a certain kind of job (and advisors, apparently, are told _they_ are failures unless their students get a certain kind of job). This is, of course, completely untrue.

I did a lot of soul-searching when hitting the job market, and decided quite quickly that a large research university or museum really wasn’t for me. These places had expectations to roll in hundreds of thousands of dollars in grant money (at a time when NSF grant application success rates are at or below 13%) as well as to crank out a certain number of graduate students. I didn’t want the stress of the former, but it did take me a bit to warm to the idea that not having grad students was OK. I’m now firmly convinced of this! Maybe that disappointed a few people, but at the end of the day I’m the one who has to live with my choices. In my current position (which is a pretty special place in very many ways), I get research time, excellent facilities, fantastic colleagues (both in-house and down the street), and flexibility. Life is incredibly good, and I have absolutely no regrets about the path I took.

The bottom line–and you do touch on this–is that students need to be given an accurate picture of the job market (I think most are probably fairly savvy to this by the time they hit their stride in grad school) _and_ be trained to be versatile. I very fortunately had both!

I wanted to be a VP since I was about 8 years old and when I was 13 or so I wrote to Mike Archer (IIRC) at the Australian Natural History Museum, and he gave me the “facts of life” about getting a job and what I would have to do. I made a decision to not go for it, and found myself at the age of 22 starting study at a university in order to be a health inspector. Its been OK these last 21 years, the longest I have been out of a job is 6 months, they pay is pretty good, but it can be soul destroying at times, dealing with fools, scoundrels, and outright criminals for a job. Sometimes I wished I had taken the other route, and I still read as much as I can get hold of and keep up with the news in VP…. and IP which is an interest sparked by reading the late Stephen Jay Gould.

Speaking as a graduate student who is close (but not quite ready) to apply for jobs, I have to say that this speech has gotten old. I’m sure there are some students who haven’t heard it yet, but I sometimes feel as if all anyone talks about in VP today is how dismal the job market is.

To build a bit on Andrew’s point: I think the single most productive thing we can do within SVP is to support the variety of job opportunities out there. You imply that people have taken jobs teaching anatomy out of desperation, and while that might be true of some people, I know others who truly love doing just that. Instead of bemoaning the lack of curatorial and R1 jobs, why don’t we applaud those who teach undergraduates, work in BLM offices, work at small museums, do fossil remediation through environmental consulting firms, etc. When we teach students that there are many paths in VP, then it becomes less of a personal crisis when they realize they’d rather have those jobs than something at an R1 University or a major museum.

Karen, the speech may have gotten old for you–but I’m amazed and alarmed by how many students I meet at SVP who have NOT been given ANY of this advice, and think it’s all going to be easy. They are the audience for this blog post.

Don, I don’t know whether to be flattered or insulted to be front and center in the photo captioned, “eager young VP students dance through the night.” Eager, VP, and dancing — YES! But I’m an Associate Professor at a medical school, and you do my institution and others a grave injustice to imply that these jobs are somehow lesser or poorly paying. My institution started me at a salary tens of thousands (!) above what Arts and Sciences faculties were offering at the time. It supports Vertebrate Paleontology specifically and intentionally, has kept every promise it has made, and is slowly developing a quality program that is — unsurprisingly — strong in Anatomy. I have a rewarding job in which I am valued as a colleague, teacher, and researcher. What is the downside of that? Of course I am ready to dance all night!

These jobs are not consolation prizes. They are a different paradigm, with different opportunities, including opportunities to take the field of vertebrate paleontology in new and interesting directions. Yes, paleontology is an interdisciplinary field in transition. Yes, tenure-track jobs are hard to find in all branches of academia. But you seem to look down on any job that is not what you define as a plum, and that does the entire field and many institutions an injustice.

Anne Weil

You should be flattered, Anne–I STILL think of you as young, and you’re a LOT younger than I am!

Certainly, the other jobs are not inferior, nor are they “consolation prizes.” The difference was that in my generation, a top post in a museum or 4-year R1 university was considered the ONLY suitable job track for my peers, and we drove ourselves REALLY hard to be competitive in those markets. All the people who mentored me thought that way, as did some of your mentors at UC Berkeley. I also considered the Med Anatomy route, but one year of human anatomy at Columbia P&S told me I was better off staying with my geology roots. I survived 35 years of teaching in small colleges with no encouragement of my research, and huge teaching loads, never getting the change to “move up”. Now it’s all behind me, my perspective is evolving.

And I’m looking at that photo again–and I can’t find you in there for the life of me–especially because it’s so blurry with the motion of the dancers…

Gold shirt, black pants, blue socks, waving my arms around (!!) front and center. I can’t be young anymore — ReBecca caught me with both feet on the ground!

The problem is much broader than just paleontology, or even academia. Overproduction of university degrees is certainly a factor. I’m in emergency management, where even 10 years ago you didn’t necessarily need a Bachelor’s degree to qualify for a decent job. Now you’re not competitive for an entry level position without a Masters degree. EM has always been a small field, and it used to be that actual specialized EM degrees were quite rare. (My own degree is in military history; hey, I was in the army at the time!) Then came 9/11, and a ton of new jobs were created – most of them grant funded – and every university started offering homeland security degrees/certificates. But ten years later, those post-9/11 grant glut positions are drying up, and the supply of jobs isn’t close to the number of students graduating. That’s not entirely a bad thing for the profession, of course, as it means we have our pick of the field. But like you, I feel bad for all these bright young kids graduating at a rate far in excess of the number of jobs available.

Lastly, old timers like us should be honest that part of the problem if our generation is working longer and retiring later, rather than moving aside to make room for the next generation.

As usual, Don, an excellent post. I tell my students, and others who are interested, that today you have to be (absolutely) the best to be considered for any position even remotely related to vertebrate paleontology, let alone a job that provides any paid time for research, writing and publishing, and attending meetings. I wish it were even that easy, as there are several filled, primo positions that are not necessarily occupied by the best and brightest but by those who shout the loudest, cater principally to the press/public, and/or who have attained their status under the aegis of a single politically endowed maven in their field. It seems to me that the average scholar in any field is about as good at what he/she does as the average restaurant cook is at what he/she does, and there are a lot of places I won’t eat. This circumstance is not unique to the field of paleontology, even though the voices of charlatans seem louder in smaller groups. For any student, my advice is to find out as soon as possible what it is you want to do, then figure out a way to get someone to pay you to do it.

I would like to mention something that I haven’t seen addressed here for the consideration of those reading this post.

I come from a generation or so after Don, and I am right in front in that second photograph. I am nearly 30 years old. In the photograph, I am surrounded (in my sunglasses) by my wife and many good friends. My friends are mostly graduate students of varying levels at several institutions across the globe. I am not a graduate student. I received a B.S. in Earth Sciences (their program had a paleontology emphasis) a few years ago from Montana State and within a few months of graduation I was plucked up by an environmental consulting firm in California.

For the better part of a decade I worked as a field team member for the Museum of the Rockies. I started young (in high school) and worked with the Museum up until the week I moved from Montana to California. I loved ‘digging dinosaurs.’ I earned a decent summer paycheck doing it, filled out my resume, helped my friends find specimens for their research, and met a lot of great people from all over the world. I learned a lot about how science works as a process, and why careful data collection in the field is an uncompromisable necessity. During my stint as an undergrad, I did a few small research projects, some based on my field work, others on whatever interesting things came my way. They all led to posters at some SVP meetings, and even a few manuscripts. It was good experience.

By the time I was finishing my bachelor’s degree, I knew that I loved working with scientists and contributing to research, but I wasn’t quite ready to make the jump into grad school. There were a lot of variables to consider (the job market certainly was one of them) and I wanted to be sure that if I was going to commit time and money to another degree that I would be ready. I decided that I would take some time off from school and realistically assess what my priorities were. Although I didn’t feel ready for grad school, I knew I wanted to work in paleontology in any fashion that I could.

During my last summer of work in the Hell Creek formation with the MOR I would pull up a laptop after a long day in the field and look for paleontology and geology jobs around the Los Angeles area (Full disclosure: my girlfriend [Wife now] lived in CA and we were moving in together). I was extraordinarily lucky. After less than a week of poking around I had sent two copies of my resume out. I heard back from one employer the very next day. They were an environmental consulting firm looking for a field paleontologist, and when I called them to discuss the position on the crew’s next town day, I was given the job. I couldn’t believe it. Full time, permanent, with *benefits*. Interestingly, they hadn’t appeared to be hiring but I had sent them my resume for kicks. Their previous full-time paleontologist was stepping down to pursue a master’s degree.

For the past 3 or so years I have served as a consultant/mitigation paleontologist for the greater southern California area. Before I started work as a consultant I knew absolutely nothing of this type of work, save the occasional story about, say, a mammoth uncovered in a field or a road cut. If I were to go back in time, before I started this job, and read Don’s article I would think that pursuing a career in mitigation is to be looked down upon and certainly not a valuable use of my knowledge and experience. I’m referring to this sentence:

” Now the job market is so bad that any kind of employment—community colleges, environmental consulting firms, teaching human anatomy to medical students, even if much lower-paying that the traditional university professor’s salary—is better than unemployment.”

I’ve seen others comment about this sentence from an academic standpoint so I’m not going to address those subjects. I cannot comment from that perspective because I currently do not have an advanced degree and have been removed from academia for a few years now. Additionally, I can only speak from the perspective of life in the United States. I write this strictly as a professional paleontologist who feels the need to amend “The Talk.”

Don’s tone about professional paleontology (i.e. mitigation) is written from the perspective of a very accomplished research paleontologist. His CV is voluminous. I used some of his textbooks during my undergraduate course work. He is very well known, and works very hard to produce his research. He also gives students lots of research opportunities (my wife among them). I can understand why from his point of view, after years in his field teaching, researching, and writing, employment by a consulting firm would seem unfitting. It doesn’t make much sense to go from that to monitoring a pipeline installation in the middle of the Colorado Desert. But “The Talk” isn’t for people like Don. It’s for people like me- people whose academic careers still lie mostly ahead of them.

Mitigation paleontology is a far cry from a research lab where you may call the shots. Your research is directed by where land development happens to occur. Because of this, within the course of a few months you can find yourself working in a wide array of units- from a college campus housing project in marine shale to a solar field on an ancient desert lake shore to a transmission line in Paleozoic limestone to an oil well pad in uplifted estuarine sands. Sometimes you find some cool stuff, and lots of times you don’t. Brief periods of excitement followed by long periods of the day-to-day grind. Days in the field can be long and tiresome. At times it feels like there is little reward to the work. Mitigation doesn’t appear as glamorous as the “plum jobs”, but it is *important* and it needs good, qualified paleontologists.

The landscape of career possibilities is ever changing in our field. With the passing of the Paleontological Resources Protection Act in the US, paleontological resources were granted their most comprehensive protection in American history. Because of this, agencies like the USDA Forest Service have been revamping their guidelines for the assessment and protection of fossils. This means that more and more projects are going to need consultant paleontologists. Historically, construction projects situated in regions containing fossils have had very little oversight from scientists. The presence of a monitor on site, or a consulting firm doing a museum records search or a literature review for a project area, is a fairly recent development in the US. In California where I work, we are lucky to have several tiers of protection for fossils here, whether it be Federal (PRPA), State (CEQA, NEPA, CA Public Resources Code) or Local (County and City General Plans). Because of these measures, every project undertaken on public lands within this state must include a consideration of its potential to have adverse effects on paleontological resources. That means that a company wishing to modify the ground for structure installation must hire a consulting firm to investigate the sensitivity of the underlying bedrock units and evaluate their potential to yield significant fossils. The BLM and the USFS use a system called Potential Fossil Yield Classification (PFYC) to rate geologic units for their paleontological sensitivity. Something like the Morrison Formation would receive a (4) on this 1-4 scale whereas a volcanic tuff would receive a (1). Using these guidelines, firms like the one I am employed with research the literature and contact regional museums inquiring about fossil sites near the proposed project’s area of potential impact. We then determine whether or not a paleontologist should be on site to monitor ground-disturbing activities. If it weren’t for the people in these positions, we would certainly be losing irreplaceable specimens that those with the “plum jobs” conduct research on.

To sum up, what I am doing for my career right now may not be the gleaming finish line for many students who are pursuing a paleontology path, but I find it to be satisfying. I get out into the field a lot. I do a fair bit of research and writing. I am the middle-person between the people who don’t care about fossils and the people that do. I am a protector of our irreplaceable natural history. It fits where I am in life right now, and I am contributing to the preservation of our shared natural heritage in much the same way a collections manager or preparator does. Professional paleontology certainly seems to suffer from a distinct notoriety, like it isn’t “good enough” or is somehow a second-class or dead end job. But you have to be smart to survive in this field. You have to be good with people, and you have to know what laws apply to where you are working. You have to be adaptable to working in many different environments, and you do get to see some amazing sights and go places sometimes where even a BLM permit wouldn’t get you.

I don’t want this to sound like I have a chip on my shoulder about anything because I don’t. I have many friends who are currently pursuing degrees, or are professors or researchers and I am very happy for their successes. And for the most part, Don’s points about the competitiveness of the field should be heeded. But lots of good, talented people work in mitigation. Some PhD’s even own consulting companies (and make pretty good money). Lots of paleontologists float their time between degrees or semesters by working monitoring gigs for a few months or a few years before moving on to something that better suits them.

Consider this from here on out: Don’s idea of a “plum job” is only that if it’s *really* what you want to end up doing. Working with a consulting firm, or a BLM office, or a Forest Service station isn’t a waste of your knowledge, your skills, or your energy. It can be the ultimate utilization of your talent. The best and brightest of our people need to be calling the shots in all professional niches, not just the Ivy League. The idea that academia is the single best pursuit is historically outdated now. The landscape has changed, and it certainly won’t help paleontology as a whole if students are told that the only worthy career path leads to a brass plate on a mahogany door.

I agree with you, Lee. Currently I’m also serving as a consulting paleontologist for an environmental firm here in LA, so I know that world pretty well. My point is that when I was trained, and when most VPs (until recently) were trained in grad school, we were all judged on whether we could find good academic jobs that allowed us to continue doing research and contributing new ideas and material to VP. THAT model is indeed vanishing, as both you and I agree. Certainly, working in environmental consulting, government agencies, etc. are worthy careers, but they largely do not pay as well as academic jobs (especially compared to top universities), nor do they have the job security of tenure. In my own career in consulting, I’ve watched my workload go from too much to nothing for months as the contracts come in or don’t come in–a tough way to make a living if you need a steady income. I’ve watched lots of my friends and former students working hard for months, then laid off for years when the demand drops. It’s not an easy way to make a living, even if you do find it more rewarding.