How the other half lives

Ever since I was a 4-year-old, hooked on dinosaurs, I knew that I wanted to study paleontology for the rest of my life. By the time I was in fourth grade, I was the only kid in my school who knew anything about dinosaurs (this was in the early 60s, before dinosaurs became cool for kids). I was asked to lecture about them to the sixth graders, and so I knew I liked to teach. Once I got into college and followed the normal route to a career in paleontology through my Ph.D. at Columbia University and the American Museum in Natural History in New York, I was committed to becoming a college professor. Starting with teaching at Columbia and Vassar, then at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, and then 27 years at Occidental College in Los Angeles, and at Caltech in Pasadena, I’ve been extremely fortunate in teaching at elite institutions with outstanding students every place I’ve worked. Most of my time has been spent in small private liberal arts colleges (Vassar, Knox, and Occidental), where the classes are small and full of dedicated, bright students who mostly want to learn and generally work very hard. I got to know every student in nearly every class very quickly, and got to be good at reading their faces to make sure they understand. I always challenged them without pushing them past their breaking point. I was very proud of the mature, thoughtful scholarship our senior geology majors would produce after four years of the best teaching and opportunities. I’ve been nominated for teaching awards many times and won a few times, and I always have alumni and alumnae coming back and telling me how important my class was in opening their eyes or changing their lives. At small private colleges where the tuition is high, we give them their money’s worth with highly intensive, personalized education (I have involved hundreds of students in my research over the years, and about 45 students have more than 50 published scientific papers co-authored with me). We know immediately if a student is missing from class (it’s hard to hide in a class of eight, but even in a class of 32, I kept track). The college practically flipped out if a student missed 2-3 meetings in a row without contacting us—we were instructed to notify the Dean of Students for any student doing poorly on a test, or showing signs of slipping, since they don’t want anyone to drop out if they can help it. And we were proud of our high retention rate, and virtually all our students graduated in four years.

After 35 years of teaching, I was prepared for a change, so I left Occidental when I reached the minimum retirement age of 58 to focus on my research and my writing. From the time my sabbatical began in May 2011 through fall of 2012, I was writing non-stop, and five different books finally came out this year, delayed by more than 1-2 years beyond what I expected. I had hoped that the books would be published 2 years earlier, so I would be able to replace most of my old salary with royalties this year and next. Unfortunately the unnecessary and sometimes stupid delays by my publishers meant I won’t be seeing real royalties on most of these books until 2015. To supplement my income until the royalties are enough to remain fully retired, I chose to return to teaching part-time. The only place where someone of my rank and experience can teach part-time these days is at junior colleges, so I’ve now been teaching at three different colleges: Pierce in Woodland Hills, Mt. San Antonio College near Pomona, and Glendale College, near where I live. All three are considered among the best of the junior colleges in California, so these students are supposedly better than those in the lower-ranked junior colleges. I expected there to be a drop in the caliber of most students compared to the elite private colleges where I’ve always taught, but I was teaching Intro Physical Geology and other subjects that I’ve done dozens of times, so at least I didn’t need to do much class prep—I know that material cold. I was told not to dumb down the course material in any way, because my course content was supposed to be transferable and the equivalent in rigor of the same course in a four-year college—so that’s the way I taught it.

What caught me by surprise, however, was not the caliber of the students. In every class, I’d have a least 10 out of 35 who were as good as my Oxy students, showed up every class meeting, worked hard, and got the good grades they deserved. The biggest difference lies in the motivation and attitude of the rest of the students at all three J.C.’s where I’ve taught, and I’m told this is the norm everywhere. Unlike students in private liberal arts colleges, who are there full-time, paying high tuitions, and living on campus, the average J.C. student is very different. Many were not college material when they left high school, and cannot really handle college-level instruction and writing and comprehension yet, and may have poor study skills. To be fair, many were working full-time jobs and had families and other demands on their lives, but generally the good students who were in that bind still made their best effort to attend, and contacted me if they had to miss something. Consequently, in every class I’ve taught at the J.C. level, we have this strange pattern. In the first three weeks, there is this stampede to fill every seat in the class, because most other classes are full and students will often sign up for anything that has an open slot. Then, after the week 3 “census” (when we tell the college who is officially in the class at that point), attendance drops drastically. By mid-semester, less than half of the original 30-35 students continue to attend, and it’s only a core of about 10-15 students who show up each day motivated that I see through the rest of the semester.

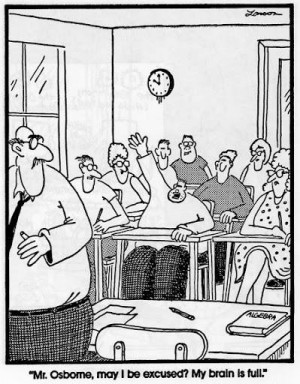

Believe me, I do everything I can to encourage attendance! I stress many times in the first weeks and in my syllabus that attendance is required to pass the course, throw pop quizzes often in the early part of the semester, have assignments almost every meeting that helps me track who’s still trying, and base my exams heavily on lecture, so they cannot pass them if they were not here. They get this reinforced loud and clear nearly every class meeting, but still the attendance lags. By mid-semester, about half the class has so few points that they cannot do any better than an “F”—but many of them do not bother to drop or take a “W” (Withdrawn), but stay on the class list and get their inevitable “F.” Some never even show up for the final exam at all; others show up at the final after weeks of no attendance and somehow think they can pass the final without having a clue what we did. During one semester, I gave a quiz or test on every lecture, which was overkill and became pointless when they still don’t show up. No matter how I taught the course, at least half of the class flunks each semester.

After a while, I began to realize what was going on here. This last semester, I warned them that if they missed two class meetings in a row without contacting me, I’d exclude them from the class. When I did this, I got protests from students I hadn’t seen in weeks! It turns out that many of the students are just parked in classes for which they have no interest just to keep parents off their backs (or the parole officer, in some cases). They are forced to enroll in classes to get their tuition checks, but once the first three weeks pass, they have no further interest in learning or attending, yet they want to keep their name on the list so the parents (or parole officer) doesn’t know they’re blowing off school. There is almost no real penalty to them to take an “F”, since they can take a course three times without passing before they’re prevented from trying again, and the tuition is so low that flunking costs very little. Most of these students have no real interest in a four-year college so their GPA is not really a motivator. Thanks to FERPA rules, we’re not allowed to discuss student performance with anyone without the student’s permission. Thus, they can be enrolled but not attending all semester, and no one will know until the final grades arrive—at which point, it’s too late for the parents or anyone else to undo the mess. All of my faculty colleagues knew this implicitly, but they were all resigned to the fact that it’s the way the system works. Junior colleges take almost anyone, even if they do not have college-level writing or study skills, and lets them sink or swim due to their own effort (or lack thereof). A few students are really motivated and using the J.C. as a cheap way to get the basic courses out of the way at low cost before transferring to an expensive four-year school. Others are “returning students” (older, more mature students who have already been in the work force), and they’re really hard-working and dedicated, because their life experience has told them how valuable time in college really is. They’re the ones at the top of the grade curve every semester. But the majority simply have no idea what to do with their lives, and waste everyone’s time and money signed up for classes they don’t attend as a substitute for unemployment or for dead-end jobs. It’s not a great system—but that’s what it has become.

Another thing that struck me was the huge difference in learning styles and what is demanded of students. In an elite private liberal arts college, students are expected to be articulate and be able to master and understand complex ideas, and to write about them fluently. We reinforced this emphasis with lots of writing and critical thinking in practically every course. Since classes were small, they rarely took multiple choice or true-false tests, but were expected to understand and write clearly about whatever topic we had taught them. Consequently, my exams are all essay questions that require understanding the subject and explaining the crucial point of the question clearly in your own words. I’d often frame the question in a realistic scenario, such as “A creationist comes up to you and says [something ridiculous they know how to debunk]” or “You hear the announcer on TV say [something wrong that they can clarify]“. These are practical examples of why it was important to deeply understand the topic, and be able to use it in real life, which is a real skill that makes the course worthwhile. In my entire 35-year career, I prided myself in never once giving a multiple choice test, even when I had a class of 80 students early in my career, and each had taken a 5-page essay test that I had to grade by myself. (I never once had grad student teaching assistants to help me, since I’ve always taught at liberal arts college with no grad program).

When I started teaching at J.C., I explained my pedagogical style to the department chairs who hired me, and they were all encouragement. But then I began to notice a big difference in the results on my tests. The students who worked hard generally were able to answer the questions in a correct and articulate fashion, just as my Oxy students could. The rest could barely put down one irrelevant sentence! Most of the tests given at a J.C. are multiple-choice and true-false, where you can guess your way to passing if you study just enough to associate a concept with a possible answer. Clearly, these students had been tested in this fashion all through grades K-12, and were still being tested this way in J.C. But what does it prove about your mastery of a subject if 25% of the time in a four-choice question, you will get the answer by random guessing? Does it really measure whether you have mastered a topic, and can think about it and articulate your ideas? NO! By contrast to my realistic essay questions based on real-life scenarios, no one ever comes up to you in the street and asks you a question, then gives you multiple choices! This even further reinforces my contempt for what multiple-choice tests do to pedagogy, and what kind of student they produce at the other end. Of course, I realize that in a big university with gigantic classes of 100 or more, no other system is practical, even with teaching assistants doing the grading. But I’m not sure what kind of “education” this produces. What I do know is that when our liberal arts seniors graduated, employers were eager to snap them up and asked for more of them, especially in preference to students taught in the big universities. They knew that students with a Vassar or Knox or Occidental education could be counted on to be able to write well, think independently, solve problems, do their own research with limited supervision, and show up and do their work on time.

Thus endeth my rant. After 35 years in the trenches of college education, and authoring five leading geology textbooks (two more in the works), I thought I’d seen everything. But now I better understand how my colleagues in huge universities with hundreds of students, in lower-ranked institutions, and in junior colleges, view the daily struggle with students over their education. I’d have burned out long ago if I’d had nothing but classes where more than half of the students didn’t give a shit. I now really appreciate how lucky I was to be at elite colleges for most of my teaching career.

A large part of the problem is that most of those students shouldn’t be there in the first place. There is a fascination with getting a college education, as if it will solve everything. Yes, we need good scientists, researchers, teachers, accountants, and whatnot, but the guy who changes my oil and the plumber and the roofer don’t necessarily need bachelor’s degrees. Don’t get me wrong; I would like to see everyone have the opportunity, and many students will shine given the chance, but college will be wasted on a large number of young people. Trade schools should have a larger part in the system.

I agree with David Hewitt. We have come to believe as a society that the trades are somehow “lesser” than jobs that require a college degree; you often hear politicians and pundits opining that every kid deserves a college education. But I’ve been to college — state college — fairly recently (as one of those old fogies who studied hard) and met a number of upper-division students who were not there because they wanted to be there. It showed in their work, and their mentality: they just needed good enough grades to keep off academic probation, so they could keep getting grants or tuition money from parents. They were there for a piece of paper, a degree, after which they would figure out what they really wanted to do with their lives. It was a sad situation.

This collection of elitist nonsense illustrates the fundamental problem pervading American education. Anyone can teach students who are motivated. It takes a real teacher, someone who loves the students more than the subject, as one aspect of their character, to understand how important it is to inspire dedication among students at every level in the system, and an convey an understanding of why a subject is important. In a modern democracy, EVERYONE needs a college degree or its equivalent. That plumber, or the guy who changes your oil, that you disrespect walks into a voting booth and cancels your contribution.

Jim, you’re full of it. I’ve been teaching as an adjunct for 25 years, and I know exactly the phenomenon Prothero is talking about.

No, “anyone” cannot teach students who are motivated, and, no, it isn’t a teacher’s responsibility to “inspire” everyone, including those who shouldn’t be there.

We recently had to junk a writing course that was designed to give an extra “lift” to students who scored below 500 on the SAT by offering an extra hour of instruction every week. It didn’t work.

Furthermore, when I had students read and write about essays with subjects related to evolution (Gould, Dawkins, Eiseley, etc.) half of them screamed at me in their evaluations of my course and accused me of “attacking their religion” and “laughing” at them in class.

In some respects higher ed is on the way down in the USA, but as Prothero indicates there will always be good students around to make our teaching jobs worthwile.

If you really think ‘…it isn’t a teacher’s responsibility to “inspire” everyone, including those who shouldn’t be there…,’ you are a clerk, not a teacher. Go sell shoes.

I attended Central Oregon Community College in Bend, Oregon (a JC) and Oregon State University. Didn’t finish. Changed my major from zoology to psychology and back to zoology. Dr Prothero is fortunate that he teaches mostly people who pursue careers in Earth science. If he taught courses for non-majors he would encounter some of what Mikeb does.

Examples: “I’m a business and finance major. Why do I have to know this?”

“How can knowing about the Ice Age help me get a good job and earn a living?”

“This is so hard!”

And of course, there’s “How can they say that potassium-argon dating proves that early humans lived 2 million years ago when the Bible says blah,blah,blah. . .”

Jim, you missed my central point. I’m an award-winning professor, and my JC students who show up LOVE me–but there’s nothing I can do to inspire students who don’t want to be there, let alone students who never show up.

Jeez, Donald, that makes you quite the shoe salesman!

I agree 100% that everyone needs a college degree, or at least a college degree level of general knowledge and reasoning ability. We can see all around us what the effects of not mandating this are.

But take a look at the practical side of things. How are you proposing to make this work? Look at me for example. I was one of those motivated students. My attendance was almost perfect, I got good, sometimes excellent grades. But between being talked to sleep by some professors, being scheduled out of my education by others, and the general organisational chaos and pointless politicking, I flunked. How do you propose to help me to a degree?

And if you can, here’s the next challenge: How do you deal with people who simply aren’t smart and who don’t give a fuck about, or even disdain, ‘book knowledge’?

Some things seem solvable. Many people start at college before their time; it should be easier to start college later in life, but at least where I live the universities charge double for enrolment to anyone over twenty or so. We should get better professors too; most are utter shits. But while I’m much closer to your view and extremely upset at Prothero’s disdainful attitude, I don’t think it’s going to be practical to give everyone a college level understanding of the world.

Furthermore, looking at those who do make it, yet still screw up the world, and the fact that universities keep sucking in students even though they know they’ll shit out 2/3 of them, I am not at all convinced that universities as they are now are a useful thing to have around.

Thank you Jim for your perspective, and to others for contributing to this important discussion. There are huge differences in the elite traditional colleges, and those more recently created public institutions. To be a true democratic society, we need to give everyone a chance. I agree that many students entering the public university college system aren’t ready, but in many of those cases, it is because our system has failed them. I do agree, that there are students who don’t care and aren’t interested. But I also know that there are many barriers that interfere with student attendance: poverty being one of them, self esteem and motivation because of prior poor experiences, the cost of having to pay for additional developmental courses, the longer time to completion because of working full time to support families and only being able to attend part time.

I would strongly recommend reading Mike Rose “Lives on the boundary” and “Why School?” The issues are complex and run deep through our educational and political systems. We need to have a variety of educational opportunities to serve our diverse populations. It is the public schools that serve the most diverse populations, which requires a lot of creativity, patience, intelligence, compassion, energy, respect and understanding on the instructor’s part. Instructors need to have multiple approaches and a gift for understanding and compassion with individuals who have potential, but need support.

The diversity in our society will continue to grow, and the need for post-secondary education will continue to grow. If we only believe that certain students are promising, then we will have larger and larger portions of our population who will not be able to start or complete higher education, and won’t be able to contribute economically and politically. Underprepared students are not going to magically go away, this is not just a recent issue, nor a temporary one. Our education system must no longer be underprepared to help these students succeed.

Technical colleges and community colleges serve a very important and ever increasing need in our society to offer additional education for those students who have not been given adequate preparation for private colleges that cater to a specific population of privileged students.

Professor Prothero was very lucky to teach at elite schools and work with motivated students. But students who attend less privileged colleges are very lucky to have instructors who are versed in Universal Design, who understand that all students are capable of learning – but what they learn, if they learn, and how they learn is both the responsibility of the student (they need to show up and do the work), AND also the responsibility of the educational & social system (provide opportunities and access for students who had poor schooling at institutions with underfunded programs, who grew up in families and communities where education was not encouraged, for students who don’t have role models in education and careers.) Instructors of diverse populations need to be open to learning new ways to engage a diverse classroom, they must begin to realize that many students are prepared to learn, but in ways that the dominant culture doesn’t recognize. Rather than seeing students as deficient in areas, we need to realize that it is our education system that is deficient in providing a variety of learning options and different, more appropriate assessment options.

Again, read Mike Rose, or Deborah Brandt “Literacy in American Lives” or Lewis, C., Enciso, P., & Moje, E. in

“Reframing sociocultural research on literacy: Identity, agency, & power” or Gutirrez, K., Moralez, P. & Martinez, D. “Re-mediating literacy: Culture, difference and learning for students from nondominant communities” from the journal Review of research in Education.

An old and late, great friend of mine, Page Smith, an American Historian and founding provost of U.C. Santa Cruz has a wonderful book on this subject, much ignored by the Ivory Tower types. One may have one now for postage.

Killing The Spirit.

http://www.amazon.com/Killing-Spirit-Page-Smith/dp/0670828173/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1391108463&sr=1-1&keywords=killing+the+spirit+higher+education+in+america

“In a modern democracy, EVERYONE needs a college degree or its equivalent. That plumber, or the guy who changes your oil, that you disrespect walks into a voting booth and cancels your contribution.”

First off – where did he show disrespect for a plumber. and – do you have any fucking clue what it means today to be a plumber? 3. What kind of arrogance is here displayed by an utter arsehole to practically demand college education for everyone? 4. What gives you idiot the impression that just because one is a plumber, a car mechanic, an electrician etc. he/she is intellectually less capable than someone with a college education and are less skilled to elect officials based on rational thought than you? Your arrogance is however something I expect from representatives of your ilk.

I hold a degree in agrology (Bsc. equivalent from a German university) that I never used in a professional context because I had more interesting things to do than the pursuit of a boring career.

I worked self employed as a plumber, gas fitter, did industrial camp maintenance in Canada’s north for over twenty five years, worked as heating technician laying out and installing hydronic systems, which took at least as much learning, thinking outside the box, troubleshooting skill as the education I had the pleasure to be able to enjoy, and now work as a salesman for commercial and residential heating and water supply systems.

My customers are tradesmen who without a college education and capable of managing their own businesses with several employees are intellectually your equal, but just not in the narrow range you would like to define it. I have all the respect for their capacity to learn, to rational thought and find them at average more interesting to engage in discussions with than your average college graduate with a big chip on their shoulder and a job at McDonald.

College education as M. Prothero described is useless for those who do not feel compelled to use it other than to

fulfill expectations by third parties or to fill some quotas.

I hail from Germany where the basis of education is – or was – a well functioning school system to either grade ten or twelve, then one had the opportunity to either choose a trade with the option to later on upgrade and attend university – my path – or enter university directly. The college route that is en vogue in anglosaxon countries never took hold in the German educational system, unless one wants to label the technical high schools as such, however those graduates exit with a marketable (or used to) degree in some field of engineering.

Thank you so much. It is so rare these days to see a display of authentic teutonic gibberish. I’m glad the kids were here to see it.

@ Jim: FYI, making fun of the grammatical errors of someone for whom English is not their first language does not make you look wise and informed. Nor does it do anything to refute their argument.

I have worked in the trades. I was an apprentice Plant Mechanic, and hated it. None of those guys needed a college education, most were vets, and they were all quite smart, articulate, and damn good at their jobs. No, tradesmen do not need traditional college, they have trade schools for that. And those schools prepare a tradesman fr better than any college will. I have zero disrespect for a tradesman, I know how hard they work, and I understand that a mechanic or electrician is plenty capable of doing what they are trained to do far better than I or any college educated person is able to do, as they have directed, concentrated training to do what they do. I did not see any elitism at all, more a practical sense of what the world is. College is not for everyone, that is very true, and college degrees are not “needed” to get by in this world, hell, most computer techs and programmers have the equivalent to a trade-school education, not college degrees. and trust me, an Oracle programmer makes more cash than most college educated folk.

Yes ,I agree, but where have all the trade schools and the non-academic schooling gone?

To Oldebabe –

Trade schools are called Technical Colleges or Community and Technical Colleges. This is where students who don’t need or want a 4 year bachelor’s can learn more specific things that apply directly to a career they want – like plumbing or mechanics or carpentry.

But not everyone is suited for college-level work. College-level work has become a stand-in for what everyone really needs to know: stuff that SHOULD not only be taught, but mastered, by 12th grade. Good reading skills, coherent writing skills, COMFORT with basic math including word problems that require basic algebra to solve and basic geometry. Enough of an overview of world and national history to put modern society in context. A good idea of how government works.

My brother-in-law is a good example. He did poorly in college because he doesn’t think well in the lecture/test environment. He went to trade school and became a top-notch welder (not just anyone gets qualified to weld on Navy submarines!) He became a self-taught computer expert and ran his own computer repair business for awhile. He became an in-house tech support manager for a medium-size company. Now he’s reinventing himself again with Windows advanced certification to do tech support on a contract basis. Not bad for a kid who couldn’t get through JC classes.

We don’t always agree on political issues — we disagree on some of the premises — but I find his reasoning well-thought-out.

When we can give people like this a proper education without resorting to a four-year or even two-year college, then we will have succeeded at educating our citizens.

“But not everyone is suited for college-level work.”

I’ve seen this. The results are sometimes ugly.

There’s a real pressure at our U to “retain” students because enrollment is dropping like stone as students flock to Community Colleges. In my writing courses, I’ve had 1/3 of the students fail outright because they are simply illiterate. It is not to be believed sometimes. I love the subject of the history of evolutionary thought and have attempted to use it as a subject for writing projects. About half the students hate me for it and saying I’m “shoving” my ideas “down their throat.”

We are a land grant U in New England, too. It’s scary sometimes. Adjuncts are under great pressures here because of cost overruns, budget cuts, and revamped work load formulas, so I’ve dropped the evolutionary readings from my syllabi because they’re too controversial. It’s depressing to no end.

“College-level work has become a stand-in for what everyone really needs to know: stuff that SHOULD not only be taught, but mastered, by 12th grade.”

Well put. There’s no question that having an educated populace is crucial in a democracy. But that’s not the same as saying everyone should have a college degree.

My sister teaches remedial English at community college, and her experiences match Dr. Prothero’s. Our education system failed these kids long before they went near a college classroom.

A bachelor’s degree certainly isn’t for everyone, and many jobs are learned on the job. Unfortunately, many jobs that don’t really need a 4 year degree, require it or you can’t apply. It is a “lazy” way of screening through 100 – 200 applicants.

Yes, unfortunately many students don’t get what they need in high school – but percentage-wise it is the less privileged students attending less privileged schools. When politics and budgets run the education system, it can be difficult to offer what each student needs. And when a student grows up in culture that doesn’t encourage schooling or a student’s basic needs of food, shelter and safety aren’t even met – how can we expect them to value education or be prepared to learn – when they live in a community where they don’t see anyone moving out or forward, and it is a daily challenge to survive?

Sounds accurate. Many students are not ready for college level work. It’s absurd to put a student who hasn’t got basic study skills and got a C in HS algebra into a college class on calculus and think that the reason for the student’s failure is the professor’s elitism. If the students haven’t got basic writing or study skills and we think that attending college is important, then the student needs to take those kinds of courses before enrolling in the serious subject material.

Absolutely. The gap needs to be filled somewhere. Right now it seems that many institutions – whether higher ed or secondary are saying – that isn’t my job. It’s got to be somebody’s job – to help students who need basic skills attain them. and to help students who want a college degree, but are under-prepared to become prepared.

Welcome to the world of public community college. I am constantly on my students about taking pride in their work and their writing skills are atrocious. I have had colleagues tell me to lower my standards and I have even been told by one institution that writing is not that important anymore. I have suggested over and over that all students that score low on basic writing proficiency tests given by the college should, no must, take remedial writing courses before being able to continue on with their studies. I have been repeatedly ignored. I fear for my future. Theses are the people who will be taking care of me when I am old.

I agree that if a student doesn’t do well in writing, they need help with it. The problem too – is that one type of assessment is a skewed view of the student’s ability. Sometimes those assessments are accurate, but sometimes not. Especially not accurate if the student is not good at taking tests, or hurries through the assessment or doesn’t take it seriously.

It is sad that often writing is seen as not important, when indeed, it is the basis of many courses. And so many people don’t understand that writing is a very important tool for thinking – the 2 are intertwined.

I am a 41 year old returning student. One of those that Dr. Prothero talks about. I have taken two of his classes, and hope to be able to take more, as I found him to be an amazing professor. Ive been lucky on my return, I have had some great, inspiring professors that have helped me get my feet back on the ground in academia. Dr. Prothero and Professor John Zayac at Pierce College switched me from a social science, Anthropology/Archeology, to deciding to tackle a hard science, geology, and likely on to specialize in geophysics. Anyone that knew me when i was a kid is very surprised. I have always loved science, but the math scared me.

I have seen the difference Dr. Prothero is talking about as a student. I went to a 4 year, SDSU, right out of high school. I was not ready to take that plunge, I was immature, stupid, and had no real idea what was awaiting me in a real college. I lasted two years, dropped out with a 1.8 GPA, and probably can safely say that I majored in party. For the next 20 years, I did nothing notable with my life. I tried different things, from mechanic to retail clerk to help desk, and nothing “clicked.” I am disabled now, but hope to one day get off of it, and decided I need to do something to actually be marketable. I went back to school. At first to just get a degree, any degree, didn’t matter to me. Just get that paper that said I was smart and had the gumption to actually finish something. What I saw was worse than I could possible imagine. Students at JC are barely educated, no motivation, and no clue. When I took my English 101 class, I failed the first time, due to time management issues, but there were kids failing because they couldn’t write. Some had issues reading. In my Math 115 class there were kids that had trouble with basic arithmetic! When i was in High school, that was required, or you didn’t graduate, period. Now a days, kids feel they can get away with anything, as long as they are pretty, can dance, or whatever. They are not serious about education, just like I was, but more widespread. I was lucky, I got a second chance. Might have taken me 20 some odd years, but I am running with it. These kids just don’t understand, with the current economy, the current direction our society is headed, they might not get that second chance. If they don’t want to be there, they should either get a bloody job, or go to trade school. Find something to do with their life before its too late. Blowing off class wastes time, yours and the professors, takes a seat up for someone that IS serious, and causes financial problems for the school and the state.

I’m really bothered by the hostility and rage in some of these comments. It seems to me that the basic conversation about the value of education generally and college specifically has been completely corrupted. Too often the question “is college worth it” is framed in economic terms, and whether college is “needed” is only considered directly in relation to a person’s occupation. I don’t really agree with this framing of the conversation.

A college degree has nothing to do with comparing the value of one person to another. Someone with a degree is not automatically better than someone without. The person with the degree is ideally better than their own past self. That is all. College gives you an opportunity to better yourself, and to do so with a selection of experts who will guide you relatively quickly through vast topics in order to get to the essence. There are certainly other ways to do that, but I find it hilarious how many people want to pretend that human beings are individually motivated to better themselves intellectually without structure and peer pressure. Is that 40 year old plumber better at critical thinking than the 22 year old college grad? More than likely, yes. But that has never been the point.

So what is it about? Critical thinking? Sure. But also understanding complex arguments, being exposed to a wide variety of fields and more importantly doing more than scratch the surface, learning to communicate complicated ideas with those around you, understanding the history of your culture, of other cultures, of science. And these things change how people think about the world. Don’t believe me then go look at some opinion polls that separate the demographics by education level.

Can you get these things in different ways? Sure. But in my experience “apprenticing” in these area with skilled thinkers and experts in their field is the most efficient and rewarding way to gain those skills. I could have read Plato, Aristotle, or Hume on my own and eventually gained the understanding that I did in undergrad. But it would have taken a lot longer and been a lot more frustrating. Being self taught at something does not automatically make you less skilled but the odds are very high that it took you a lot longer to get to your skill level than if you had been provided structure and a deadline.

Thank you Lumen for your civil tone and reframing of the question and discussion. I agree, the question is not whether a person with a college education is better than one without, and it definitely not about if a person who uses his hands to earn a living is less intelligent than someone who uses their head.

These are not either/or questions and they aren’t relevant.

There are many complex issues at hand – the motivation of students, understanding the difference between someone who has many barriers to schooling or someone who isn’t ready. Understanding that someone who isn’t ready now, may be very ready at some point in the future. Understanding that each person must find their own path and sometimes that takes many roads, risks and mistakes along the way. All those students who don’t show up because they don’t care – some do care but just have other issues. Some will come back later when they are ready. Those students who aren’t ready – it is their time to make mistakes. I work with many students who were those students that didn’t care – at one time in their past. Now they are back and motivated. We all make mistakes, and students are no different. Hopefully, we all learn from our mistakes and hopefully there are people who are helping us and not holding our mistakes against us when we are ready to change and move forward.

Coincidentally, I just came across this great article on the economics of higher education. Tldr – we can’t even sustain the current system, let alone expand it to give everyone a college degree.

http://www.shirky.com/weblog/2014/01/there-isnt-enough-money-to-keep-educating-adults-the-way-were-doing-it/

A few money quotes relevant to this discussion:

“Part of the reason this change is so disorienting is that the public conversation focuses, obsessively, on a few elite institutions…the collapse of Antioch College in 2008 was more widely reported than the threatened loss of accreditation for the Community College of San Francisco last year, even though CCSF has 85,000 students, and Antioch had fewer than 400 when it lost accreditation.”

“The value of our core product—the Bachelor’s degree—has fallen in every year since 2000, while tuition continues to increase faster than inflation.”

“The other way to help these students would be to dramatically reduce the price or time required to get an education of acceptable quality (and for acceptable read “enabling the student to get a better job”, their commonest goal.) This is a worse option in every respect except one, which is that it may be possible.”

“Many of my colleagues believe that if we just explain our plight clearly enough, legislators will come to their senses and give us enough money to save us from painful restructuring. I’ve never seen anyone explain why this argument will be persuasive, and we are nearing the 40th year in which similar pleas have failed, but “Someday the government will give us lots of money” remains in circulation, largely because contemplating our future without that faith is so bleak. If we can’t keep raising costs for students (we can’t) and if no one is coming to save us (they aren’t), then the only remaining way to help these students is to make a cheaper version of higher education for the new student majority.”

The new version of higher education should be implemented in K-12 — especially high school. I overheard a student and a teacher seriously discussing the “face on Mars” in my son’s high school. High school is failing our children on a much grander scale than community colleges…

An interesting post.

I think that the education systems in Canada and the US are deeply, deeply, screwed up. And have been for a few generations.

I suspect that this problem is, in a sort of passive-aggressive, yet nonetheless intentional manor, generally A-OK with the larger corporate world. Stupid and/or uneducated people are very easy to control, manipulate, and influence. Smart and well educated people, much less so. And, aside from the bottom-line profit motive, if there’s anything the larger corporate world thrives on and desires, it is control of the population.

All that being said, I still tend to wish that instead of returning to college for five years, as I did from 1995 to 2000, to gain an Associate Arts degree and some other related stuff, I had instead taken some kind of trades course. Even with my degree, and 15 years of professional experience, I am still unemployed more than I am employed. I was even homeless for a year from November 2005 to November 2006. Degrees, as nice as they may be, certainly don’t build roofs over your head.

Useful degrees build roofs over your head because they’re required for many jobs. A dental hygienist with a two-year community-college degree can make over $70K, while English majors wait tables.

The problem with trades is that they’ll be automated eventually :-)

Valid points, Max.

However, I think my rejoinder (other than to ponder your qualifier of “useful degrees” — what’s considered useful seems to change from generation to generation) would be to say that degrees might, or can potentially, build roofs over your head, but they are not a guarantee of such — my own case in point.

And, yes, trades will almost certainly eventually be automated, or, as is the case with such intellectual pursuits as English degrees, rendered in some other way obsolete.

One of my current beefs with contemporary educational institutions is this robotic focus on education as a specific goal to a specific career, rather than what I feel is the healthier focus of education for the simple sake of improving one’s ability to think and one’s overall knowledge.

But, then, I guess I am old fashioned, curmudgeonly, and something of a luddite.

Perhaps.

Yeah, it’s sort of a tautology like “survival of the fittest.” The fittest are the ones who survive, and useful degrees are the ones that put a roof over your head.

Speaking of which, did you see this?

http://chronicle.com/blogs/ticker/obama-questions-value-of-art-history-degrees/72073

Of course nothing is guaranteed. Even lottery winners often go broke.

What institutions focus on a specific career? Does Common Core do that? Obviously trade schools and professional schools do that by definition. A lawyer needs a law degree and a surgeon needs an MD.

Still, employers complain about a “skills gap,” though some of that is just their unwillingness to offer on-the-job training, and ignorant recruiters who majored in English and only know how to look for specific keywords in resumes.

Max, I’m a Canuckistan, so I am not familiar with Common Core.

My experience with colleges and universities in Western Canada, in particular their recruiting strategies, as well as much of what I’ve read in various media over the last 20 or so years, leads me to believe that the focus in educational institutions, at all levels, has left general knowledge skills (English, arts, intellectually-focussed courses, etc.) far, far behind, in the pursuit of specific, job-oriented, especially corporate-focussed, scholastic pursuits (business; accounting; management, etc.).

And I think that is a real shame, and a sure way to ensure the eventual decline of the human animal as a (somewhat; sometimes) rational entity.

Yes, I know that sounds a bit extreme, but that is how I feel about it. I hope I am wrong and being conspiracy-swayed, so to speak. But I don’t think I am.

As to employers complaining about so-called skills gaps, I think that is a combination of a sort of moral panic, and a reflection of a truly ridiculous increase in demand for potential employees to be way, way, way, overtrained/over-educated for any particular job. I mean, a bachelor of science for a plumbers assistant — that, is, of course, a hyperbolic example, but at the moment I cannot recall any of the actual nonsense demands for over-educated employees, but they do exist.

Max said:

“… ignorant recruiters who majored in English and only know how to look for specific keywords in resumes.”

Doesn’t that represent just about all current corporate hiring strategies? Especially the current trend of online job application forms/programs?

Financial literacy is useful and empowering in general. If anything, a lack of financial literacy is why people get ripped off and lottery winners go broke. I wish my high school taught finance. It would’ve been a lot more useful than ceramics.

In the U.S., the skills gap, especially in STEM, is a subject of debate. On the one hand, there are statistics about Americans ranking below other countries in math, science, and problem solving skills. On the other hand, as Paul Krugman argued, if companies are so desperate for skilled workers, they could just raise the salaries. They want a bigger supply of skilled workers to lower their salaries.

Also, a large number of job applicants lets headhunters use search engines to search for keywords in job applications to find the closest match.

About interviews, the senior VP of people operations at Google said this:

“Years ago, we did a study to determine whether anyone at Google is particularly good at hiring. We looked at tens of thousands of interviews, and everyone who had done the interviews and what they scored the candidate, and how that person ultimately performed in their job. We found zero relationship. It’s a complete random mess, except for one guy who was highly predictive because he only interviewed people for a very specialized area, where he happened to be the world’s leading expert.”

Whats with the references to ‘parole officers?’

I’ve had several students who were on parole, and one of the conditions of their parole was that they stay in school and pass their classes. As I said, the JC student body is a very different mix from what I was used to…

I’ve had parolees, and last spring I had someone who was still in jail (they got out to only attend classes, went right back in after class ended). They were one of the most attentive and interactive students, as you can well imagine.