The dunning-kruger effect

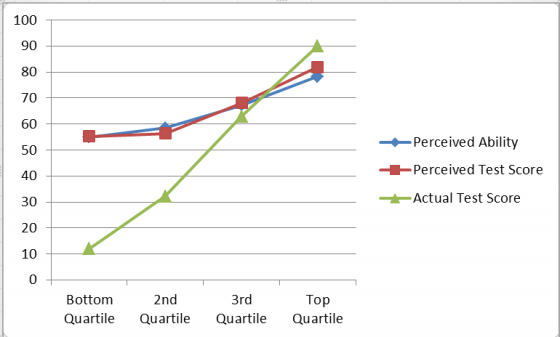

One of several graphs showing that people who know little (as revealed by tests) still think they know a lot.

“I know one thing: that I know nothing”

—Socrates

“Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge”

—Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

“The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt”

—Bertrand Russell

“The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.”

—William Shakespeare, As You Like It

“Welcome to Lake Wobegon, where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.”

—Garrison Keillor, A Prairie Home Companion

Most of the readers of this blog are familiar with the Dunning-Kruger effect (even if we don’t always know what the name means). Although the idea is an old one, going back at least as far as Socrates and Shakespeare, it was first formally named only 14 years ago by Cornell University psychologists Justin Kruger and David Dunning (not the Brian Dunning of this blog). Their title said it all: “Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments.” In other words, ignorant or unskilled people tend to overestimate their level of competence and expertise, while those who are truly expert sometimes underestimate their true level of expertise. Since its proposal and naming, it has become a well-known effect in cognitive psychology, and people have become even more aware of it in recent years due to non-experts trying to shout down people with expertise, or demagogues using the label of “elitism” to push their policies as they ridicule the experts who challenge them.

Since the original paper came out in 1999, there has been a lot of research into why the Dunning-Kruger effect is so common and what drives it. It mostly boils down to a cognitive bias related to confirmation bias (seeing only what we want to see, and ignoring the misses). In the case of the Dunning-Kruger effect, the bias is one where we cannot believe that we are wrong or less intelligent than others, so we have an artificially inflated sense of self-esteem. (And this effect is an ancient human foible, so it can’t be blamed on recent efforts to boost the self-esteem of young people, even at the expense of telling them the truth about their level of competence and intelligence).

Most of us can identify many recent examples of incompetents who don’t recognize their incompetence, often shouting out their inanities and attempting to drown out their expert critics. Some of my favorite examples include:

- —Deepak Chopra and other woo-meisters misappropriating the ideas of quantum physics and the Heisenberg uncertainty principle to give their mystical ideas a false scientific veneer. When challenged by a physicist (such as Leonard Mlodinow) who DOES understand quantum physics (as I’ve seen during debates hosted by the Skeptic Society), Chopra weasels out of the fact that physics does not support his woo, and uses rhetorical tricks to cover his ignorance of the subject. Then, in front of the next friendly audience, he goes right back to misleading his followers into thinking he’s an expert on quantum physics.

- —Creationists like Duane Gish and their ilk who have absolutely no training or firsthand experience in fossils or paleontology writing whole books about fossils as if they actually had studied them. As I showed in my 2007 book on evolution, when a real paleontologist goes through their writings, it is painfully obvious they don’t know one bone from another, but are just parroting stuff they’ve read in kiddie books, and quote-mining real paleontologists to sound like they don’t support the idea of evolution.

- —The follies of the Bush Administration, when they openly mocked the qualified experts who warned them about their disastrous policies (from chasing the non-existent WMDs in Iraq to their economic ideas, to their denial of climate science and evolution). Bush himself bragged about not thinking through things too much or using reason, but making decisions “from the gut”—and spawned a whole industry of experts who revealed that “gut-level” decisions are usually wrong, as well as comedians like Stephen Colbert whose character avoids using logic and reason and data, but makes decisions based on their “truthiness.”

- —The purveyors of quack medicines who blather on about the great benefits of their untested snake oil, and then demonize the FDA and the scientists who rigorously test their products to determine if they really work (and vigorously attack doctors like our own Steven Novella or David Gorski or Harriett Hall when these scientists point out that their “medicine” is pure snake oil).

- —The various global climate change deniers who have absolutely no training in climate science (including TV weathermen, who do not actually work on climate), who jump on the climate denial bandwagon and nitpick details in the scientific literature that they didn’t work on, and don’t understand enough about to critique it.

- —The comically incompetent efforts of Andrew Schlafly (son of right-wing activist Phyllis Schlafly) to rewrite science to fit conservative Christian ideology on his Conservapedia website. As I pointed out in

- , this includes his uninformed and ignorant attacks on evolution, climate science, geology, astronomy and cosmology, and other areas of science that creationists try to deny. But his most hilarious efforts are his attempt to deny Einsteinian relativity because he confuses it with the philosophical idea of relativism, because Barack Obama once talked about relativism, and because it’s not in the Bible! Then he shows his complete inability to understand it by bumbling through mathematical equations that prove nothing except that he doesn’t understand physics.

These examples can be multiplied endlessly, so I won’t continue them here, but let the commenters add their own personal favorites.

“Specialist Knowledge Is Useless and Unhelpful: When data prediction is a game, the experts lose out”

http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/new_scientist/2012/12/kaggle_president_jeremy_howard_amateurs_beat_specialists_in_data_prediction.html

Peter Aldhous: What separates the winners from the also-rans?

Jeremy Howard: The difference between the good participants and the bad is the information they feed to the algorithms. You have to decide what to abstract from the data. Winners of Kaggle competitions tend to be curious and creative people. They come up with a dozen totally new ways to think about the problem. The nice thing about algorithms like the random forest is that you can chuck as many crazy ideas at them as you like, and the algorithms figure out which ones work.

PA: That sounds very different from the traditional approach to building predictive models. How have experts reacted?

JH: The messages are uncomfortable for a lot of people. It’s controversial because we’re telling them: “Your decades of specialist knowledge are not only useless, they’re actually unhelpful; your sophisticated techniques are worse than generic methods.” It’s difficult for people who are used to that old type of science. They spend so much time discussing whether an idea makes sense. They check the visualizations and noodle over it. That is all actively unhelpful.

I wonder if people viewing that graph, on seeing that those with the highest actual scores underestimate their abilities, will assume that they are also underestimating their own abilities, leading to an even greater disparity in their own graph points.

That viral Dove commercial.

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=you-are-less-beautiful-than-you-think

“The video ends: ‘You are more beautiful than you think.’

However, what Dove is suggesting is not actually true. The evidence from psychological research suggests instead that we tend to think of our appearance in ways that are more flattering than are warranted.”

Also from the above article:

“Most people state that they are more likely than others to provide accurate self-assessments.”

“Of college professors, 94 percent say that they do above-average work.”

That reminds me of those Windows commercials where people claimed it was their idea. In their minds eye, they all looked like models and body builders.

Funnily enough, they seem to be the most parodied-commercials on YouTube.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is interesting but unimportant compared to how others view them. Bush is an idiot, but the voters gave him a second term, there in lies the problem.

Compare with Kerry

http://reverent.org/stupid_or_clever.html

My favorite are experts in one area who pontificate across areas in which they’re not trained. You see this a lot in bloggers, especially MDs, JDs and those with PhDs in science (of all things).

Being an expert in, oh, biology, doesn’t mean you actually know anything about economics or accounting or law or history beyond some ‘feel good’ pablum that confirms your particular bias. Yet, being no more than ill-educated laymen with, at best, a shallow understanding of complex issues and systems they stand upon high and give their dead-wrong pronouncements.

And this goes across the entire political spectrum — liberal to conservative. And while you rightly pointed out Schlafly and Conservapedia, their opposites (RationalWiki) does a lot of the same. Not so much fast and loose with hard science, but very fast and loose with science (such as evolutionary psychology) that casts doubts on their particular societal/gender beliefs.

It would be interesting to explore how this effect manifests differently in different areas. Take sports, for example. If you asked kids in a high school PE class how good they are at basketball, I would imagine the bottom quartile know full well that they are below average. (I sure did when I was that age!) Is that because their poor performance is obvious and immediate? Because it’s physical, not intellectual? Because there’s no “I just don’t test well” rationalization? Or does it have to do with peer feedback? (“I always get picked last, therefore I must suck.”)

Or how about math? Americans don’t seem ashamed to say that they’re bad at math, though they should be.

I’m not sure that poor math skills would be a motivator for most people being ashamed,any more than being a poor brick layer would be. Not that I want to equate those things myself,but that they perceive math skills as something unnecessary for them to carry out their day to day lives.

I personally attribute that to the way that math has been taught to most Americans (at least).I don’t know what the emphasis is today for training in math,but my teachers were not enthusiastic about the subject,never showed how it applied to real world situations,depended on rote memorization of operations and tables,and recited the rather dry text,without any real explanation,to the point of the whole exercise being one big abstract system that beyond the basics of addition,subtraction,division and multiplication, was just another obstacle in our path to graduation.

Later on you begin to see where those skills can be useful,and if you have the time,motivation,or need,then you can learn/relearn/master those skills,but I bet most people will not go on to more advanced maths,unless they, again,perceive that they might need them.

But shame…? I am not so sure about that.

I bet math instruction isn’t any more interesting in Korea, but Koreans would consider it more shameful to be bad at math.

It’s just a kind of basic literacy, for example to read the graph at the top of this page. Speaking of which, notice that the perceived score bottoms out at 50, but it still almost forms a line, which you could map to the actual score. So when someone thinks they got 50, assume they got 10. But it won’t work for outliers or those who have a more realistic self-assessment.

Assuming you are correct about Koreans experiencing more shame for failing at math,is the source of that shame a realization that they are missing a useful skill,or more,that they are not meeting cultural expectations?

Americans are culturally averse to doing things just ‘because I said so!’.I still believe that presenting math as a useful life skill for both employment, and for solving everyday problems (much like critical thinking skills),could produce better results than what we have been seeing.

I assume it’s cultural expectations, and math literacy is a reasonable expectation because it is a useful life skill.

Data analytics is exposing a lot of these “gut feelings” as useless.

For example, Google’s hiring process.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/20/business/in-head-hunting-big-data-may-not-be-such-a-big-deal.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Q. How is Big Data being used more in the leadership and management field?

A. …Years ago, we did a study to determine whether anyone at Google is particularly good at hiring. We looked at tens of thousands of interviews, and everyone who had done the interviews and what they scored the candidate, and how that person ultimately performed in their job. We found zero relationship. It’s a complete random mess, except for one guy who was highly predictive because he only interviewed people for a very specialized area, where he happened to be the world’s leading expert.

Q. Other insights from the studies you’ve already done?

A. On the hiring side, we found that brainteasers are a complete waste of time. How many golf balls can you fit into an airplane? How many gas stations in Manhattan? A complete waste of time. They don’t predict anything. They serve primarily to make the interviewer feel smart…

Q. Other insights from the data you’ve gathered about Google employees?

A. One of the things we’ve seen from all our data crunching is that G.P.A.’s are worthless as a criteria for hiring, and test scores are worthless — no correlation at all except for brand-new college grads, where there’s a slight correlation. Google famously used to ask everyone for a transcript and G.P.A.’s and test scores, but we don’t anymore, unless you’re just a few years out of school. We found that they don’t predict anything.

My favorite is the personality test that I took for management for AT&T, that was attempting (among other things) to ferret out ‘risk takers’,which was the flavor of the month in business practices at the time. But the thing is,that I had been thoroughly trained by their own system for the previous 20 years to be extremely risk averse,as to avoid serious (and even minor) service interruptions,which were sometimes cause for termination,if they resulted from reckless risks on the part of the technician,and the management position that I was seeking,was to oversee others whom,presumably,would also be held to those same risk averse standards.

I can well imagine that the ‘genius’ that conceived of the idea that ‘risk takers’ were a universally useful attribute to management in a company at all levels,did not realize their own reckless incompetence.Look how that mindset nearly brought down (and still might) the world’s economies.

Years ago Mobil had a programme called EIMP- the early indentification of management potential.

Out of their thousands of staff they selected the ones with the highest salary to age ratios. Then they got them to answer a questionnaire with hundreds of questions. The answers themselves weren’t important, but they looked for recruits who answered, on average, in the same way.

This is all very interesting but I don’t know how effective it was.

My favourite example is Dana Ullman and whatever dubious study has recently caught his limited attention

The Dunning-Kruger effect; Interesting research, and cute.

But does it have any ‘real world’ significances? What is the salient point to take away from all this? That we should only listen to experts or those in a position of authority? That the masses should always be ignored? A voice from the wilderness is worthless?

In reality it has simply become another technical riposte to be used in contentious debates, and is in my opinion (take that with a grain of salt, I am no debating expert, nor cognitive psychologist, and yes you can label this DK effect if you like) has little more worth than that.

And do the examples Prothero quotes have anything to do with the Dunning Kruger Effect?

Deeprak Chopra is a salesman, running a very successful business. This is all marketing talk, and although in my experience (take that with a grain of salt, I am no marketing expert, yes you can label this DK effect if you like) some salesmen at least partly end up believing their story, they largely are simply aware of what works, and just keep doing it.

Duane Gish and his ilk are men deeply brainwashed and programmed by their belief (in my opinion, take that with a grain of salt, I am no expert on religion and psychology, yes you can label this DK effect if you like) and on top of that are also salesmen for their cause. They don’t have to consider the value of the knowledge of others in unrelated (to them) areas, as they know that all they need to know is in one book.

The Bush administration’s decision to go to war is possible the very worst example Prothero could use. This has nothing to do with beliefs on anyone’s part, laymen or experts – experts were ignored, sidelined, smeared, witch-hunted out of sight. This was simply blatant lying in order to fulfill a pre-decided political and hegemonic agenda, and it already has a name; propaganda, and this example is about as shameless as it gets. (take that with a grain of salt, I am no expert on politics, and yes you can label this DK effect if you like).

Purveyors of quack medicine; salesmen. See Deeprak Chopra above.

The various ‘global climate change deniers’ (oops, strawman! – most are CAGW doubters, perhaps an entirely different thing, but I won’t digress further) consist of an array of people from all walks of life, many connected in some way to the hugely complex and varied field of climate science. Note in the much touted consensus of “climate scientists” all sorts of qualifications are accepted as being climate scientists, as long as they have included at least a short paragraph giving a hat tip to the concepts of CAGW. These include marine biologists, geologists, oceanographers, marine studies, paleoclimatologists, physicists, mathematicians, ecologists, psychologists … etc etc. (take that with a grain of salt, I am no climate expert, and yes you can label this DK effect if you like).

Andrew Schafly? See Duane Gish and his ilk above.

Again and again throughout history we see examples of men who thought differently and thought they knew better than the experts of the time, and though they were not initially the experts in their field, sometimes, just sometimes, events and history later labeled them thus.

Here is an example of the use of the DK effect as a debating tool: http://phillipjensen.com/articles/new-atheists-and-the-dunning-kruger-effect/

New Atheists and the Dunning-Kruger Effect. A regular article written by Phillip Jensen in his role as Dean of Sydney at St Andrew’s Cathedral.Originally Published:12th February 2011.

Writing in the New York Times in 2007, the Roman Catholic journalist Prof. Peter Steinfels noted that the criticisms of Richard Dawkins’ book The God Delusion come not just from the believers but also from atheists and unbelievers. He pointed to the reviews of such academics as The Oxford literary critic Prof. Terry Eagleton, The Harvard literary critic James Wood, the Rochester evolutionary-biologist Prof. James H Orr and the New York philosopher Prof. Thomas Nagel. And Steinfels could have added others like the Florida philosopher of biology Prof. Michael Ruse. The chief complaint of these critics of Richard Dawkins is his incompetence in dealing with the subject of God and theology.

It led me to this marvelously written critique of Richard Dawkins and his book “The God Delusion” here by Terry Eagleton, Distinguished Professor of English Literature at Lancaster University.

Marvelously written, very readable and worth reading for a study of that alone, but in content there is nothing but fluff, faith and handwaving “…Nor does he understand that because God is transcendent of us (which is another way of saying that he did not have to bring us about), he is free of any neurotic need for us and wants simply to be allowed to love us….” Great stuff, eh? And he is sure of this, how?

Eagleton goes on to tell tales of the existence of Jesus (probably a fascinating man with his won set of beliefs) perhaps as evidence for the existence of a God, but then tempers it all with (and I paraphrase): “I don’t know if all the forgoing is true but it seems a good thing to believe in God”.)(..and, he may well be correct in that!) http://www.lrb.co.uk/v28/n20/terry-eagleton/lunging-flailing-mispunching

Now, the question is, how does knowledge of the Dunning Kruger Effect help the average reader in such a debate? Exactly which side do we apply it to? Or are we to apply it to ourselves? Are we no longer qualified to debate anything?

I see this effect all the time in my gen ed science classes. The students who walk out thinking they aced the exams do very poorly. The ones who walk out worried that they didn’t do as well as they should, did very well. (There are, of course, students who know they failed because they barely studied and randomly picked answers.) Confidence is often inversely proportionate to exam score.

Practical upshot? If you feel like you are going to ace the exam, you need to go back and study some more.

How much of the D-K effect is nature vs. nurture, and how common is it in other cultures? The above Scientific American article gives one explanation: it’s easier to convince others that you’re superior when you’re convinced yourself. That sounds like a human nature argument, but what about the whole self-esteem movement?

Tim O’Neill’s comment about “Geologist David Prothero” getting facts wrong about Hypatia was deleted before I could reply that it’s Donald, not David.

Ha… yes, I am surprised that has gone, it was the nicest example on the page.

Yes, I did post that rather early in the morning and got Donald’s first name wrong. The fact that it was censored by him says something.

Just as we need to be careful of non-experts from other fields talking outside of their expertise, we should also be wary of scientists trying to teach history, especially when they get it completely wrong. Here is my critique of Donald’s post on Hypatia of Alexandria. Let’s see if he has the integrity and honesty to leave my comment up again this time.

A Geologist tries History (or “Agora” and Hypatia Yet Again)

Please don’t be like the fundamentalists Donald. Man up and face the fact you got it all wrong.

The Dunning Kruger effect is similar to Friedrich Hayek’s fatal conceit. With Dunning Kruger, nonexperts have an inflated sense of their own effectiveness, while with Hayek, government experts have an inflated sense of same.

I know enough about everything too be really wrong about anything. Hitler wrote in 1927 that people will not believe small lies because they tell them all the time. but they will believe lies that are the opposite of truth because they can’t believe anyone would tell them such a big lie.

Regarding the Dove commercial: ‘Beauty’ is not a concept that submits itself to statistical analysis. ‘Standard of Beauty’ is. Women are punished for looking normal (not above average in beauty) and they are punished for saying that they are beautiful (stuck-up, vain). A woman’s shame at being not good looking enough is usually internalized, while the shame of being vain by verbally stating one’s belief in one’s beauty is external, much like the example of a Korean being more likely to be ashamed at not being good at math than an American. The point is: the search for meaning within data is never ending and always becoming more nuanced. The goals of the interpreter are as important to the outcome as the data and method of inquiry.

@ Moses ZD: excellent point! I have often been astounded not only by the penchant for people with professional degrees and PhDs to opine outside of their expertise with the expectation of by unqualified belief, but by the zeal with which many people will grant their unqualified belief, because ‘he’s a doctor, so he knows’ Sad…

So Gabriel, where does that leave the rest of us while you weep?

Should we never read up on, study, debate and learn on a new topic that interests us?

Must the ‘expertise’ in any particular field remain forever in the hands (minds?) of a few acclaimed experts?

The Dunning Kruger effect is little more than an interesting observation, and a useful distraction for those wishing to avoid becoming involved in the substance of a debate.

You cannot see it, but I have been giving every comment you have made an invisible “‘nucks”. I had to let you know how refreshing it is to see both sides of the conceptual coin described so clearly. It is a rare thing.

If you have a book published somewhere, I would love to read it.

I see the Bush bashing, but how was unemployment under him [even though some sell snake oil to claim higher unemployment and higher inflation are really lower]? What is that fossil record? All well and fine, but one cannot help think of Thomas Sowell’s point of all the experts and academics who supported Communism, Socialism, and other ideologies (remember from history that Stalin was the darling of the American academics, so much that his mass destruction was intentionally overlooked, while many compared him favorably to Hitler, including those in FDR’s administration). The point is that the smart academics, including in the most transparent administration ever, have produced far worse than Bush’s “gut decision” (even though a Stanford economist states Bush was far from making gut decisions, but that destroys the ideology). Though I digress, the point is that experts can produce howlers like, “giving insurance to 30 million people will save two trillion” [think how much money would be saved if we gave everyone a million dollar insurance policy with a new BMW?). I could add many examples, like Mussolini being adored by FDR and many envious of Mao, but the list is lengthy. Instead of defending one’s policies though, it is easier to upend Edward Bellamy’s book to become “Looking Backwards,” and just blame and play grievance politics.