The Rough Fist of Reason!

This week I’d like to share something a little different: an out-of-copyright detective story published way back in 1916. “The Rough Fist of Reason”—one of the “Strange Cases of Magnum, Scientific Consultant” by Max Rittenberg (1880–1965)—tells the tale of a fictional on-site skeptical investigation into the operation of a slick Spiritualist medium and a perplexing photograph of an astral manifestation. It is charmingly dated and over the top, and yet it is also astonishingly familiar. It echoes not only much of the language and arguments of the modern skeptical movement, but also some of the clichés and ongoing debates of our field. Like some modern portrayals of skeptics in fiction (I’m reminded here of Hugh Laurie’s Dr. House or Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock Holmes) Magnum is a hard, overconfident debunker with little empathy for the purveyors or consumers of paranormal ideas: “He was an inveterate opponent of superstition or nebulous fancy presented to the world in the garments of science, and wherever possible, liked to smash a fist into it.” In his merciless materialism, he is both brilliant and callous; admirable, and yet conceivably dangerous to the wellbeing of those he encounters.

An ongoing common theme of the work that Michael Shermer and I pursue at the Skeptics Society (see for example my recent two-chapter piece “Why Is There a Skeptical Movement?” [PDF]) is the importance of studying the work of the skeptics of the past—from Lucian of Samosata’s debunking in second century Rome, to the investigations and insights of early American skeptics like Mark Twain (PDF) and Benjamin Franklin, to the hard won lessons of early twentieth century pioneers like Joseph Rinn and Rose Mackenberg. It’s essential for skeptics to learn from the lessons of the past, and appreciate that we’re caretakers for the work of those who have come before.

To do that requires not only serious study of that skeptical work in itself, but also consideration of the cultural context in which the work took place. “The Rough Fist of Reason” was widely published in newspapers in 1916.1 It reflected the general understanding of the public at that time—including a public awareness of skeptical investigation that may seem surprising to us. Rittenberg expected his readers to recognize that the (already decades-old) talking-to-the-dead business of the Spiritualists occupied a twilit middle ground between authentic religious experience and fraudulent con-artistry. He also expected readers to be familiar with the concept of science-based committees2 that investigate and in many cases expose the trickery behind apparently supernatural phenomena. There had been many investigation projects by that time, many high profile prosecutions of mediums, and many widely publicized exposés. Generations had grown up with these ideas. Four decades before the invention of the Magnum character, the New York Times could already say, “In this country at least, nearly all the so-called phenomena of Spiritualism have been rationally explained. … Multitudes of exposures have been made of performing ‘mediums,’ whose marvelous phenomena were simple enough when laid bare to the public.”3 Thus, when Rittenberg had Magnum identify himself as “frankly a skeptic,” he presented his detective as the newest iteration of a traditional stock character. “The skeptic” was a template as easily recognizable to readers in 1916 as to television viewers of The X-Files in the 1990s, or to current readers of this blog.

For all its square-jawed bluster, “The Rough Fist of Reason” also raises ethical questions that trouble skeptics today—or which ought to. What guidelines govern skeptical interventions? Is truth (assuming we in fact know how to pursue and reliably demonstrate truth in our areas of claimed expertise) the only ethical principle to consider? Or ought we also to be concerned about the wellbeing of the people we encounter in our work?

—Daniel Loxton

The Rough Fist of Reason, by Max Rittenberg (1916)

At the phrase “spirit photographs,” Magnum interrupted his client brusquely.

“Spirit, photographs!” he repeated. “My dear young lady, I can get them made for you seven and sixpence a dozen, cabinet size, platinotype, finished off with an art mount. It’s a mere question of faking the plates—taking a double exposure. Any raw amateur could turn the trick. When I was on the occult investigation committee, a couple of years back, we had hundreds of such photographs submitted to us. Sent, mark you, in perfect good faith. The people who had them believed them to be indisputable evidence of spirit visitations. Utter rubbish! Trickery, and transparent trickery at that! Why, the so-called spirit faces were demonstrably taken from existing pictures or photographs. The same pose of head, the same turn of expression.”

It was an unusually long speech for Magnum to make. With his quick impatience, his habit of condensing a quart of thought into a thimbleful of crystalized concentrate, he would customarily have answered an inquiry of obvious foolishness with an emphatic “Rubbish!” and allow his tone of voice to drive home the reason behind the summary. But in this instance he felt very strongly and lengthily on the matter. He was an inveterate opponent of superstition or nebulous fancy presented to the world in the garments of science, and wherever possible, liked to smash a fist into it.

His client, Miss Cicely Cotterell, was a modern young woman, those bright-hard college girls who are not abashed by any authoritativeness on the part of man.

1916 readers would have been familiar with the idea of investigation committees. The 1884–1887 Seybert Commission organized by the University of Pennsylvania was just one such project. An example closer in time for the readers of this story would have been the highly skeptical Metropolitan Psychical Society, based in New York City, established in 1905. Members of that group participated in a widely publicized investigation and exposé of a medium named Eusapia Palladino in 1910.

She answered quietly: “I knew you had been on the occult investigation committee, and that is why I came to consult you. You would be able to see at once through any of the customary trickery—anything that had been done beforehand by spirit mediums.. But, before I explain further, tell me this: Do you believe in possibility of supernatural happenings?”

“There is no supernatural,” retorted Magnum, a little decomposed by this quiet self-assurance. “Anything that happens is ipso facto natural. There is the supernormal—something outside the range of ordinary experience.”

“We mean the same thing,” said Miss Cotterell, “though your wording is more accurate.”

“Go on.”

“Do you believe that the soul can leave the body and travel through space?”

“Beliefs are outside my province. Science deals with facts—verifiable repeatable facts. I’d have no quarrel with all that theosophical, astral farrago if they’d put it forward as theory instead of assertion. Now my time’s valuable, so come down to your particular case.”

He glanced up at a large, bold-faced clock which was a conspicuous feature among his plain, workman-like office appointments.

“My aunt, Miss Dallas, has been dabbling with theosophy and spiritualism for a year past. Up to now we have regarded it as a harmless hobby—”

“We?” interrupted Magnum.

“I am representing her family.”

“And heirs?” asked Magnum pointedly. He had no liking for the modern young woman in general, and in regard to Miss Cotterell in particular, he wished to see her decently subdued.

“I want you to understand clearly that my interest in the matter is not mercenary. I’m very fond of my aunt. I want her to live as long as she can naturally live, happily and peacefully. I don’t care it she never leaves me a penny. I have my profession—I’m independent.”

“School?”

“Inspector of factories. However, that’s beside the point. I was saying that my interest in the matter was not mercenary. I hate to see her fooled or tricked, that’s all.”

“And you want me to expose the trickery?”

“Yes, if it is trickery.” Miss Cotterell added a barbed point: “And if you are able to see through it.”

That found Magnum in a tender spot. He had been about to refuse the request, but this doubt of his abilities spurred him to action. “Get down to the facts,” he snapped.

Miss Cotterell produced from her purse-bag a rough-trimmed silver print and handed it over to the consultant. It represented an impression of a woman’s form in a seated position—showing as through the vague outlines of the clothing—and to one side and above it another form apparently issuing from the first, smaller, and less definite in outline, like a cloud of vapor. The rest of the photograph was plain darkness.

“My aunt,” she explained. “What is your opinion of the photograph?”

“There are many ways of faking a print,” answered Magnum cautiously.

“I took it myself,” was the quiet reply. “I exposed the film myself, and developed and printed it myself. I bought all supplies without his knowledge of where they came from.”

“His? The medium’s?”

“Mr. Slivinski is not exactly a medium.”

“Sounds a tricky name.”

“He’s rather a famous man in the occult world, and leads a psychic society in London. He may be genuine—frankly, I don’t know. But if this photograph of mine is the result of some trickery I want it explained and my aunt taken away from his influence before she becomes obsessed with it.”

“Can I see the room where this photograph of yours was taken?”

“It was at Slivinski’s own house.”

“That’s awkward. If I went there he would be sure to recognize me.” Magnum was under the impression all London would know him by sight.

“I don’t think so. You might take an assumed name and pass off as an earnest inquirer. He holds weekly meetings for his circle. The next gathering is tomorrow night, at nine o’clock.”

Magnum hunched his bushy eye-brows at the strange photograph she had passed to him, so suggestive of an “astral body” leaving the material body of Miss Dallas. In view of the girl’s explanation of having exposed and developed and printed it herself, it was something quite beyond his previous experiences in the chicanery of spirit mediums. It was no faked film, no faked print. The “cloud of vapor” might conceivably be accounted for, by the painting of the background with concentrated sulphate of quinine, which, invisible itself to the human eye, would yet affect a photo- graphic plate.”4

But no such theory would account for the unearthly manner in which the body of Miss Dallas gleamed through the vague outlines of her clothing. It was ridiculous to suppose that she would have painted herself from head to foot with sulphate of quinine.

The mystery of it piqued Magnum. Was it possible that this was an instance of the “supernormal” which he was ready to admit? Or was it merely some up-to-date development of the spiritualist’s armory of illusion?

“I’ll come,” decided Magnum.

“It would be best first to call at my aunt’s house,” suggested Miss Cotterell. “She dines at seven. After dinner we can drive together to Slivinski’s.”

He nodded assent, and announced his fee for the investigation.

At seven prompt, Magnum’s taxi was at the door of the quiet residence on the height of Campden Hill occupied by Miss Dallas. Outside and inside it suggested leisured dignity of age and amply sufficing means. Miss Dallas herself, a woman of sixty, silver-haired, delicately framed, almost childlike in her simplicity of thought —in a word, Victorian—made a striking contrast to her self-reliant young niece.

Miss Dallas belonged essentially to the class of the “learners,” those who must have some stronger will to obey and rely on. Her confidential maid, her niece and no doubt this fellow Slivinski were at present, the dominants in her life.

Magnum was concentrating on the one problem of that strange “astral” photograph. He decided without hesitation that if some fraud had been perpetrated there had been no connivance on the part of Miss Dallas or the confidential maid, an elderly woman devoted to her interests. It was equally evident that Miss Cotterell was sincerely attached to the aunt.

The dinner was somewhat of a trial to Magnum, whose gastronomic tastes ran to large porterhouse steaks or hearty beefsteak pies, solid, substantial puddings and strong cheeses. At Miss Dallas’ table no meat was served, or any heavy dish, and only for Magnum’s benefit was wine introduced. She herself drank a bottled table water imported from the Caucasus and supposed to have very special medicinal qualities, in the manner of all high-priced table waters.

“My health has improved so wonderfully since I came to know Mr. Slivinski,” she informed Magnum. “I am so glad you are coming with us to see him. You will like him, I am sure. His teachings are so restful and so beautifully expressed. I always feel that merely to listen to his voice is to be carried to a higher plane.”

“I’m interested in that photograph taken by your niece,” responded Magnum. “I’m frankly a skeptic.”

“Yes—the photograph—isn’t it wonderful? I had always felt the truth of Mr. Slivinski’s teachings about the astral plane, and now that I have the evidence of it, in my own person—now that I have seen my own astral body emerging from the shell of the material body—I am comforted beyond measure.”

“I suppose Mr. Slivinski will be building a temple to house the society,” suggested Magnum, groping for the mercenary interest he imputed to the spiritualist. “Something large and costly.”

“No, I don’t think so,” returned Miss Dallas. “Our modest little circle contents us all.”

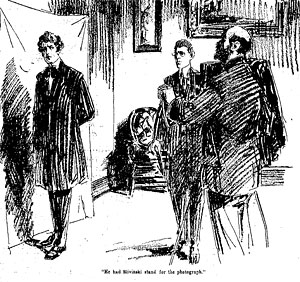

An illustration for “The Rough Fist of Reason” as it appeared in the Hamilton Evening Journal in January, 1916.

After, dinner, Miss Dallas’ pair-horse carriage came to the door—the modern motor jarred against her tastes—and they drove across London to Sliviniski’s flat in Hampstead. This was furnished simply and tastefully, nor was there any open evidence of the paraphernalia of the medium. Magnum expected to see the familiar black cabinet with black velvet curtains from which the “spirits” usually emerge under cover of a kindly darkness, or the trick pictures on the wall. They were conspicuously absent from the drawing-room into which the visitors were shown. About a dozen others of the circle were already present, nearly all women, and this number presently filled out to twenty-five or thirty.

“Where did you take the photograph?” whispered Magnum to Miss Cotterell.

“Over there,” she answered, pointing to a side wall papered in a sober, self-colored grayish-green.

“Any curtain or screen behind your aunt’s chair?”

“Nothing—only the bare wall.”

“Lights down, of course?”

“Not entirely. I could see quite plainly.”

“Was Slivinski in the room?”

“Yes—over by the fireplace.”

“All the the time you were exposing the film?”

“Yes.”

“A time exposure?”

“He told me to allow five minutes.”

Anton Slivinski entered to take his seat at an open reading desk raised on a platform and flanked by a pair of palms. He had the face of an ascetic and dreamy, far-away eyes. He made his way silently to the desk and sat there in dreamy immobility while a lady at the grand piano played a nocturne of Chopin. Then, without formal preface, he began to read from translated work of Indian mysticism. His voice—as Miss Dallas had indicated—was musical and finely modulated.

At the conclusion of the reading there was another pianoforte selection, and that was followed by an address from Slivinski. His subject was “The Cosmic Consciousness,” and his thoughts on it were mystical in the extreme, vaguely nebulous like a misted scene from a faraway realm of fancy. To the practical Magnum it was a score of nothing wrapped round and round by swathings of beautiful meaningless words, but the audience seemed to find in it some comfort he was totally unable to appreciate.

The gathering broke up into knots and coffee was handed round. Magnum edged away to the side wall against which the photograph of Miss Dallas had been taken, and scrutinized it for some evidence of trick paneling. He could find nothing to bolster up his suspicions.

Presently he was introduced to Slivinski. To Magnum’s relief and disappointment, the mystic did not penetrate his alias, but welcomed him as an earnest inquirer, with courteous words and offers to elucidate any point in the lecture which might have caused difficulty or doubt.

Magnum had nothing to ask about the address, which was far too involved and nebulous to offer opportunity for attack, but he went directly at the subject of the mysterious photograph.

“Do not let us lay too much stress on that,” replied Slivinski gently.

“Why not? It seems to me highly important. As a skeptic, I welcome any form of material proof.”

“Ah, you are a materialist, and so you value the unessential. I would like you to develop the thought that the true essential is the existence of an astral body which those of us who have purified the inner vision can see as plainly as you perceive the material body. The photograph tells me nothing new. I have long since arrived at the purification of the inner vision. My life-work is to train others to the same end. Such a photograph is merely a proof to those who half- believe, and in itself it is has no true value.”

He was winding words around Magnum. The scientist cut into the web with the rejoinder: “Could such a photograph be repeated? Could I, for instance, obtain that effect with a camera?”

“Undoubtedly you could, under the right conditions. Miss Dallas had very carefully prepared herself with fasting and with prayer, and when I perceived that her aura was in the condition of being able to impress itself on a photographic emulsion—which is only rarely in the case of an initiate—I asked her niece, who like yourself is a materialistic skeptic, to expose a film and so register the condition in a visible form.”

“Could I obtain that effect with Miss Dallas?”

“I must repeat, sir, that the necessary conditions are but rarely obtainable, and since the test was only made to satisfy Miss Dallas I cannot see any valid reason for repeating it. It would merely distress her, and it could prove no more than has already been proved.”

“Could I obtain that effect in your own person?” persisted Magnum.

“With myself, yes, almost at any time, for I have long passed the stage of the initiate.”

“Then will you allow me to do s0?”

“To what end?”

“To convince myself.”

“You sincerely wish to be convinced?”

“I am always open to conviction.”

“I must repeat, sir: Do you sincerely wish to be convinced?”

For all this gentleness of speech and courtesy of manner, Magnum realized that the mystic was a man of strong will and determined purpose. He was forced to answer, “Yes.”

“And receiving the proof you desire, will you be prepared to withdraw your doubting, freely and without reservation?”

Magnum was little used lo being cross-examined in that fashion. In his ordinary professional work, it was he who did the probing, but in this instance, hiding identity under an alias, he was at a disadvantage. “Yes, yes!” he answered impatiently, and, after further parleying, an arrangement was made to carry out the test on an evening of the same week, at Slivinski’s flat.

•••••

Magnum neglected no possible precaution that occurred to him. He armed himself with a stereoscopic camera instead of a single-lens instrument; he bought his supplies with extreme circumspection and tested them minutely; he took with him to the flat a screen to place behind Slivinski, backed with a coaling of metallic lend, and he had young Meredith, his laboratory man, to accompany him and watch for any discoverable trickery. He had Slivinski stand for the photograph in a part of the room chosen by himself; and, not satisfied with one exposure, he took three separate photographs with different exposure times.

Late that night, Magnum and Meredith were eagerly developing the plates and printing them on bromide paper. In silence they surveyed the result through a stereoscopic projector. It showed the figure of Slivinski in full solidity gleaming through the vague outlines of his clothing in the same fashion as MissDallas, but more strongly defined—a weirdly impressive effect. The only important difference was that “no cloud of vapor” showed to one side.

“Damnation!” was Magnum’s very unscientific comment.

“I have never heard of such an effect before,” said Meredith mildly. “Do you think it possible that this is really the aura of the man?”

Magnum began to pace the laboratory, puffing furiously at his curved briar pipe; and he went on and on with his pacing until the patient Meredith fell asleep at the bench. The scientist awakened him without ceremony. “I’ll take photographs of ourselves under the same conditions of lighting,” he announced, and proceeded to do so.

The result was entirely negative—a mere vague outline of clothing and head.

“You’d better go to sleep on the office couch,” offered Magnum with belated humanity. “I’ll wrestle this out myself.”

The wash-leather dawn of misty London, peering in timidly through the grimed skylight of the laboratory and shading his eyes against the glare of the electrics, found Magnum sleepless, tousled, reeking of rank tobacco, with smarting tongue and eyelids and harsh skin, perplexed, baffled—but not beaten.

“There must be some simple explanation!” he kept repeating to himself. “Both of them giving the same effect, the old lady and Slivinski. … Same effect, same cause.”

The dawn, gathering courage, was now staring unwinkingly at the unwashed, disreputable figure of Magnum. St. Paul’s boomed out the hour of six, and a host of city churches hastened to confirm the news. Magnum suddenly realized that another working day had begun. Switching out the lights in the laboratory, he went to the office and found Meredith heavily asleep. Magnum’s motor launch was locked in a little water kennel at the back of the laboratories. Magnum unmoored her and sped up the river to Westminster, where he repaired to a Turkish bath near Victoria street.

An hour later he was lying on a couch in the cooling-off room, combining the process with breakfast and a chat with the masseur.

“You’re looking off color, sir,” mentioned the bath attendant, who knew him well. “You ought to try a half bottle of Koslof Liman water.”

“What’s that?”

“One of our regular clients, a Russian gentleman from the Embassy, told me about it, and since then I’ve recommended it to a lot of other gentlemen, and they all find it does them good after—” he was about to say “a night out,” but discreetly changed it to “when they’re off color.”

“Let me see it,” said Magnum idly. “All these waters are wonder workers, every single one of them, if you believe the advertisements.”

The attendant brought a small bottle in characteristic dark-blue glass, decorated with a label in Russian characters, and poured out a tumblerful.

“I’ve seen that stuff before,” exclaimed Magnus. “Quite recently. It was at—”

“The Embassy gentleman says it’s full of radium, sir.”

“How many bottles have you got here?” asked Magnum sharply.

“Nearly two dozen, I think.”

“I’ll take them all.”

“Very good, sir,” said the pleased attendant.

On the evening of the next day, Magnum was again, by appointment, at Slivinski’s flat.

“These are the prints of the photographs I took of yourself,” said Magnum.

The mystic glanced at them without interest. “They tell me nothing new,” he answered, “though doubtless they would seem -wonderful to you. I trust you arc now satisfied.”

Magnum produced another print. “And this is one taken of myself in my laboratory. As you will see, I also seem to have a strongly-developed aura.”

Slivinski’s brow contracted slightly as he looked at the bromide print of Magnum. “You are a man of intense personality,” he replied, “and by training you would pass quickly through the stage of the initiate to the state of the adept.”

“And here,” pursued Magnum, “is one of my office cat, wrapped in an old coat. She also seems to have a strongly developed aura.”

The mystic remained silent.

“And finally,” clinched the triumphant Magnum, “here is a photograph of a bottle of table water wrapped in brown paper. Its aura is more powerful than yours or mine or the cat’s. … Koslof Liman water, the same as you recommended to Miss Dallas.”

Slivinski remained stock still for many moments, his dreamy eyes fixed on some far-away vision. “Well?” asked Magnum sharply. “What have you to say for yourself? All these photographs correspond to the one taken of Miss Dallas, with the exception of the “cloud of vapor” effect, and no doubt you got that by smearing some of the water on the wall to the side of her chair. That water contains something new to me. It’s not radium emanation alone. When I’ve time to spare I shall investigate it further.”

“What I have taught is the truth,” said the mystic with slow, religious intonation in his voice. “An eternal, imperishable truth—but not provable to the materialistic skeptic. In order to help one of weak faith, I arranged to show the invisible in visible form. I told you on our first acquaintance that I laid no stress on the photograph. You have discovered the method, but you have not disproved the essential verity of my teaching! Let me beg of you to let the matter rest.”

“Most decidedly not!”

“Faith has wings of gossamer—do not crush them with your rough fist of reason.”

“These photographs of mine will be placed before Miss Dallas, and she will draw her own conclusions.”

“You fool!” flung out Slivinski with sudden white-hot passion. “You blind fool!”

That was not the type of wording to influence Magnum. He replaced his bromide prints in his pocket, left the flat, sent the result of the investigation to Miss Cotterell, and turned to his ordinary professional work.

•••••

It was a week later when Miss Cotterell came to see him at the Upper Thames Street office. She was dressed all in black, and her features were drawn with pain.

“I wish I’d never shown you that photograph or asked you to investigate,” she told him with a break in her voice.

“You don’t mean that—?”

“Yes; you and I between us have killed my aunt, and I shall never forgive myself.”

“Good God!” exclaimed the horrified Magnum. “I didn’t dream she—”

“When I told her, it brought on a heart attack, and she never recovered from it.”

“It seems incredible that a mere revelation of trickery should produce such a result!”

“There was more behind than I knew of,” she continued with bitter self-reproach. “An early love affair… something she had always cherished… and Slivinski told her that when she came to the stage of the adept she would he able to meet him again on the astral plane. That was how his teachings gave her such comfort. And I shattered her hope. She had nothing more to live for. Oh, why, why did I ever presume to interfere!”

“The gossamer wings of faith,” murmured Magnum.

References:

- For example, see Rittenberg, Max. “Strange Cases of Magnum, Scientific Consultant: The Rough Fist of Reason.” The Syracuse Herald (New York). April 30, 1916. p. 5; Rittenberg, Max. “Strange Cases of Magnum, Scientific Consultant: The Rough Fist of Reason.” Hamilton Evening Journal (Ohio). January 29, 1916. p. 3

- Consider the University of Pennsylvania’s 1887 Seybert Commission. See William Pepper et al. Preliminary Report of the Commission Appointed by the University of Pennsylvania to Investigate Modern Spiritualism in Accordance with the Request of the Late Henry Seybert. (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1920.)

- “Investigating the Spirits.” New York Times. Jul 8, 1875. p. 4

- Preparation with quinine sulphate or bisulphate was indeed a known technique for producing patterns that could not be seen with the naked eye, but which would nonetheless appear, as if by magic, in photographs—potentially duping an unsuspecting photographer. See for example, Hopkins, George M. “Spectral Photography.” Scientific American, December 27, 1902; Vol. 87., No. 26. p. 464; Fraprie, Frank R. and Walter E. Woodbury. Photographic Amusements: Including Tricks and Unusual or Novel Effects Obtainable with the Camera. (Boston: American Photographic Publishing Co., 1931.) pp. 121–122. (My copy dates to 1931, but previous editions go back to 1886.) Fraprie et al explain the technique of exploiting this effect: “Take a colorless solution of bisulphate of quinine and write or draw with it on a piece of white paper. When dry, the writing or design will be invisible, but a photograph of it will show them very nearly black. It will be obvious that a number or tricks may be played with such a mixture.” Scholar of the history of Spiritualism Frank Podmore explained one such trick: “the figure of a spirit may be painted in sulphate of quinine or other fluorescent substance in part of the background.” Podmore, Frank. Mediums of the 19th Century: Volume 2. (New Hyde Park, New York: University Books, 1963.) p. 125 (footnote 2).

Like Daniel Loxton’s work? Read more in the pages of Skeptic magazine. Subscribe today in print or digitally!

You should check out “A Master of Mysteries” by L. T. Meade, an 1898 short story collection about a skeptical investigator of supernatural phenomena, who always finds a scientific explanation…even if the science is a bit crackpotty by today’s standards. I reviewed it on my blog a while back… http://dustandcorruption.blogspot.com/2010/05/master-of-mysteries-by-l-t-meade-and.html

Thanks for the tip! Sounds right up my alley.

Awesome! Thanks for sharing that. I’m thinking this must be made into a SyFy show immediately. Except they’d set it in the present day Pacific Northwest and all the mysteries would turn out to be paranormal in origin.

Vagrarian, do you own an original, or do you have a reprint version you would recommend? I see many print on demand vendors offer the book through Amazon, but some of those may be detestable OCR versions rather than scans or edited reprints.

Daniel, I got off Gutenberg.net and read it on my Kindle. I don’t have an original copy, alas. I would commit mayhem for one. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/22278

Another ancient debunker (though not skeptic) was Daniel of the Bible story, who used common sense (and footprints left in dust) to show that humans, and not statues, were consuming food offerings. Slightly ironic, but an amazingly modern sounding bit of literature.

As a skeptical Daniel myself, that lovely little story has long been a favorite of mine! I’ve discussed it in the pages of Junior Skeptic, and give a brief account of the tale in “Why Is There a Skeptical Movement?” as well (PDF, p. 73, endnote 91).

What an inspiring story – I think I should aspire to kill off clients’ aunts. Well, if we can believe that the truth kills them. So far I haven’t managed to kill any despite the fact that I’m far more vulgar than Magnum P.I. when telling people things are nonsense.

Good story. We may forgive the author’s intemperate brevity and remember the tragic women of the watch factory.